SOUND: THE MATERIALS OF MUSIC

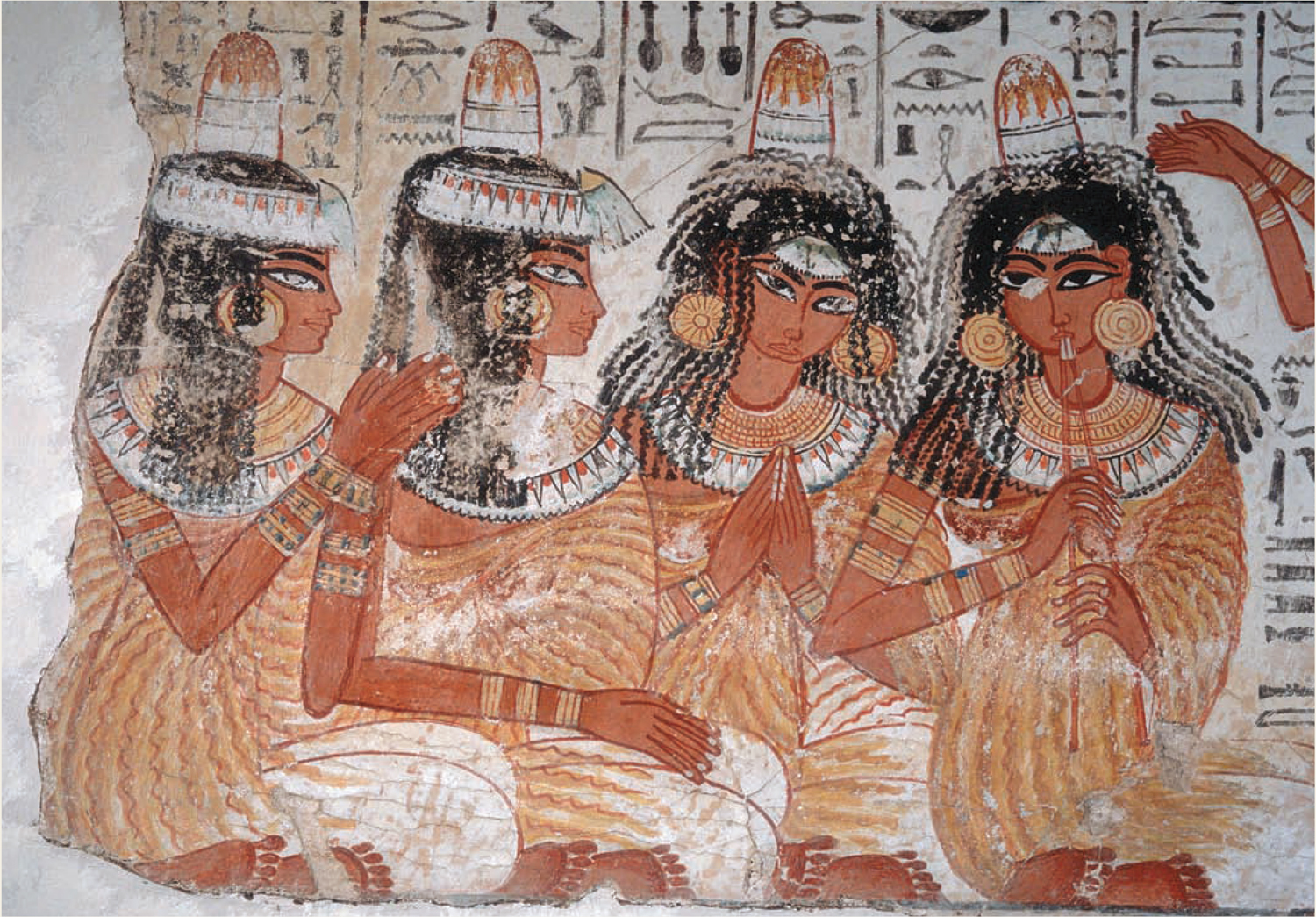

Music has always occupied a central role in human life. This wall painting from the tomb of Nebamun, a nobleman who lived in Thebes, Egypt, during the Eighteenth Dynasty, portrays female musicians listening, clapping, and (in a part of the painting not reproduced, to the right) dancing to the music of the double-reed pipe at a banquet. Although musical activity is represented in Egyptian paintings and reliefs from as early as 2500 BCE, this painting dates from around 1350. The musicians are wearing perfumed cones of scented fat on their heads.

MAIN POINTS |

|

• Music is sound organized in ways meaningful to people in a specific time and place.

• Each music culture organizes the four main characteristics of sound—quality, intensity, pitch, and duration—in distinctive ways.

• Musicians may reproduce, reshape, or discard familiar sounds each time they conceive and perform music.

INTRODUCTION

How do we talk about musical sound? Different cultures have different ways of thinking and talking about music. Commonly used terms within soundscapes emerge from a consensus about what constitutes music and its important characteristics.

WHAT IS MUSIC?

As we learned in the Introduction, vibrations give rise to sound waves, which in turn affect the eardrums and set into motion a multistage process of auditory perception. So ubiquitous is sound in our lives that we have a term for its absence—silence—which is a relative concept. In fact, we rarely experience absolute silence, since the basic processes of our bodies and nervous systems provide a constant sonic backdrop to our existence.

While a wide variety of sources can produce sound, such as the pounding of a hammer or the scream of a tea kettle, music is purposefully constructed from particular types of sounds that have over time come to convey meaning within a given cultural setting. Music, therefore, can be defined as organized sound that is meaningful to people within a specific time and place. Beyond this very general description, we must look to individual soundscapes to understand what sounds people select and how they define music.

Music can be defined quite differently by people in different cultures or subcultures. For instance, although in many traditions people define music as organized sound that has a tune or melody, among some of the Venda people of South Africa music “is believed to be founded not on melody, but on a rhythmical stirring of the whole body, of which singing is but one extension.” As a result, although some Venda children’s songs do not have tunes, their regular rhythms lead Venda people to define these sounds as music, not speech.1

Listening is a part of our daily experience and can catch us by surprise. Here a Celtic harp lures a young listener away from the bustling market in Tréguier, Cote d’Armor, in Brittany (France).

Even closely related music cultures sometimes categorize the same sounds differently. An example is a type of singing performed by Inuit, Chukchi, and Ainu peoples living in widely separated polar regions of the Canadian Central Arctic, Siberia, and Japan. All three peoples use a similar and distinctive singing style, almost certainly derived from a common source, characterized by the fast inhalation and exhalation of breath.2

In Listening Guide 6, we hear one type of Inuit katajjaq (“cat-ta-ZHAHK”), translated as “vocal game.” The katajjaq (pl., katajjait) is generally sung in a playful manner by two Inuit women who stand or sit face to face, sometimes holding each other’s shoulders, competing to see who can keep singing longer. Eventually, one woman runs out of breath and both begin to laugh.

The rapid breathing in and out enables the singers to produce two additional sounds called “voiced” and “voiceless” sounds. The vocal cords produce voiced sounds when they vibrate while being pressed together, and produce voiceless sounds when held apart. The result is a complex sound that is very distinctive, as heard in Listening Guide 6.

Among the Inuit today the katajjait are considered vocal games, not music. However, the Chukchi and Ainu peoples perform similar songs as part of ritual dances and consider them to be a type of musical expression.3 Therefore definitions of music may be shaped not only by preferences for different sounds in different settings, but also by disagreements in closely related cultures as to whether particular sounds constitute music or not. It is worth noting that the main entry under “music” in the leading English-language music dictionary cautions us that it is impossible to provide “a universally acceptable definition” of the word “music” because of the many different ideas about what constitutes music in different places at different times.4