CHARACTERISTICS OF SOUND

If music is the purposeful organization of sound that enters our consciousness through the sense of hearing, we need to subdivide the listening process into manageable parts. We can break down sound into four acoustical characteristics that are useful in all cultures: quality, intensity, pitch, and duration.

At the same time, we will take into consideration which aspects of musical sound are regarded as important within a given tradition, and what other special concepts might be applicable. We will pay attention to insider words, concepts, and expressions that are used to represent and explain musical sound within a specific soundscape.

Our exploration of the characteristics of sound is made possible by the availability of sound recordings that give us access to music traditions that little more than a century ago could be studied only through live performance in widely scattered locales (see “Looking Back: The History of Changing Sound Technologies”). These recordings enable us to compare and contrast the characteristics of musical sound across geographical and cultural boundaries.

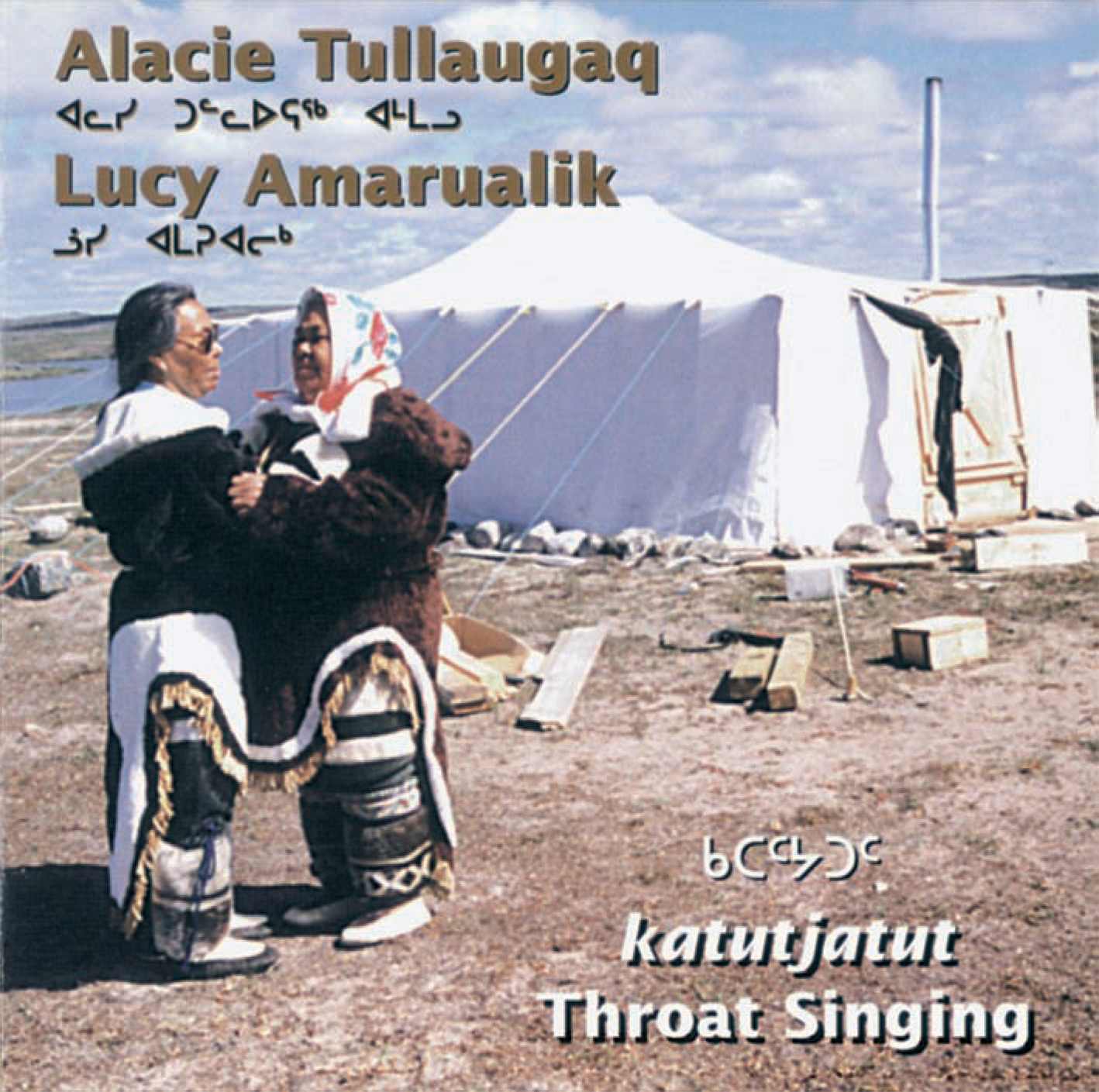

Alacie Tullaugaq and Lucy Amarualik, female Inuit artists from Puvirnituk, Nunavik (Northern Quebec), are pictured on the cover of their album Katutjatut Throat Singing, which was chosen “Best Traditional Album—Historical” at the Canadian Aboriginal Music Awards. Tullaugaq and Amarualik, who learned singing from their mothers and grandmothers, have performed internationally.

LOOKING BACK |

|

THE HISTORY OF CHANGING SOUND TECHNOLOGIES |

To study a range of cross-cultural music traditions, we are dependent on sound recordings, a technology invented in the late nineteenth century:

1877–78 Thomas Edison invents and patents cylinder phonograph

1888 First commercial phonograph. Introduction of six-inch wax cylinder, able to record and play back music

Phonographs no longer record sound, shifting industry focus to marketing prerecorded sound:

1895 Emile Berliner introduces prerecorded 78-rpm twelve-inch discs

1902 First recording of the tenor Enrico Caruso

1910–12 Pathé and Columbia stop manufacturing wax cylinders, leaving only prerecorded cylinders and discs on market

Recording technology fed the development of other sound-related industries:

1920 First regular radio broadcast in the United States

1924 Microphone and electrical amplifier first used in sound recording

LATE 1920s Custom-built portable disc recording equipment created

By the mid-twentieth century, new technologies enhanced the quality of recorded sound and new methods of sound recording emerged:

1945 45-rpm seven-inch vinyl disc first appears

1948 33⅓-rpm vinyl long-playing disc (the LP) appears

1948 First commercial magnetic tape recorders are manufactured

1955 Stereophonic recording. First stereo LPs and stereo tape recorders

The late twentieth century saw the democratization of sound recording through a series of new technologies permitting easy recording as well as portability:

1963 Cassette tape created

1969 Dutch physicists begin development of the Compact Disc (CD)

1979 Portable cassette player is introduced

1982–83 CD players first sold

1986 Digital Audio Tape (DAT) introduced

1992 MiniDisc comes on market

1995 Enhanced CDs appear

1998–PRESENT MP3 system compresses audio files into digital formats that take less computer memory than previous technologies

2001–PRESENT Introduction of small, portable digital music (MP3) players that can store and play back thousands of tunes and the increasing ubiquity of solid-state digital sound recorders

QUALITY

The distinctive sound of a particular voice or instrument is termed its quality; sometimes musicians use the expression quality or borrow the French word timbre to refer to this characteristic of sound. Quality is the first among the four characteristics because without it we would not perceive much in the way of difference between musical sounds. We already learned in the Introduction that each musical sound is constituted of a spectrum of harmonics ascending above a fundamental tone, produced by the vibration from either a musical instrument or the human vocal cords. Our discussion of quality, therefore, must take account of sound sources, the voices and instruments that produce musical sound and whose vibrations give rise to our perceptions of quality.

We have learned that each sound source generates certain harmonics that render its sound distinctive and enable the listener to distinguish between a piano and a guitar, or to differentiate between the voices of two singers. Factors such as details of the construction of an instrument, including the materials from which it is made or subtle aspects of craftsmanship, also contribute to the quality of a sound. For instance, an instrument made of metal has a different quality than one made of wood.

The pioneer ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore (1867–1957) used a wax-cylinder phonograph to record the language and music of Blackfoot Mountain Chief in 1916. Many of her recordings are preserved in the American Folklife Center’s Archive of Folk Culture at the Library of Congress.

There are also other aspects of sound production that shape quality. These include the ability of a voice or instrument to begin, sustain, and end a sound. The onset of a sound is called its attack; the way in which a sound dies out is termed its decay. Wind instruments generally have an abrupt attack because of the need to force air into the instrument and the quick action of their keys. Keyboard instruments such as the piano use special pedals to help sustain tones that would otherwise decay rapidly. Some sound sources, such as the voice and string instrument heard in Listening Guide 7, are able to begin a sound gradually and to sustain it as long as the breath holds out, or to prolong a sound by pulling the bow slowly over the strings.

SOUND SOURCES: THE VOICE

The voice has always been a source of considerable mystery, in part because, in contrast to many other instruments, its sound-producing mechanism, the vocal cords, are hidden from view. Most of us recognize different vocal qualities, since many co-exist within the same geographical or cultural arena. The wide array of vocal sounds all around us is probably the most persuasive evidence that no single vocal quality can be considered to be a “natural” singing voice. Rather, as we have already heard with examples of khoomii singing and katajjaq, the voice is an enormously flexible instrument that can produce a variety of sounds, some quite unexpected.

There are many ways in which the voice can produce a distinctive sound. The ability to render an upper harmonic audible as practiced by khoomii singers, or to produce the range of vocal articulations as women do in performing a katajjaq, is relatively uncommon, and for this reason has attracted the attention of outsiders. Yet there are common vocal articulations that produce qualities encountered in many soundscapes that are easily recognized. These include a purposeful vibration of the tone, referred to in Western music by the Italian term vibrato; excellent examples of vibrato can be heard in the voice singing the long song in Listening Guide 7 (see p. 32). String instruments can also be played with vibrato introduced by pressing the string and rapidly rocking the hand ever so slightly and is commonly heard in performances on the Western violin. However, the bowed instrument that accompanies the singer in Listening Guide 7 uses very little vibrato, producing a sound described as a straight tone.

0:56 |

Date of recording: 1977 Performers: Sumya (voice), accompanied by Orchirbat on a bowed stringed instrument Function: Used for entertainment and celebrations as well as for personal pleasure |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The different qualities of the female voice and the bowed stringed instrument, which can be distinguished from each other even as they perform virtually the same lines

Terminology describing vocal quality is often subjective—for example, the term raspy is sometimes used to describe a singing voice that is rough or gruff in quality. Sometimes words describing vocal quality connect a musical sound to other aspects of the culture, revealing qualities important to insiders within the tradition. For instance, food-related terms are quite commonly used to describe vocal quality, such as the description of a “sweet” vocal sound. Adjectives relating to temperature, such as “warm” or “cold,” are also frequently applied to vocal quality, as are attributes of “bright” and “dark” tones borrowed from the visual domain. Instruments are frequently described by the materials from which they are made; we speak of “reedy” or “brassy” sounds.

A singer can alter the quality of her voice by generating the sound from within the chest, head, or nose. Generally, the chest voice produces a low, powerful, throaty vocal quality often heard in rock music. A good example of a chest voice is heard in the recording of the long song in Listening Guide 7: compare the chest voice used for most of this excerpt with the head voice heard at 0:40 on that same track. In European music, the male head voice is known by the Italian term falsetto. The contrast between the quality of chest and head voice of a male singer is usually more marked than in the female voice. A buzzing vocal quality produced by using the sinuses and mask of the face as sound resonators is sometimes termed a nasal quality and is heard in many music cultures, ranging from those of the Mediterranean area to Chinese opera and American country music. In Listening Guide 8, we hear a strong nasal quality in the voice of American folksinger Dorsey Dixon.

SOUND SOURCES: INSTRUMENTS

Musical instruments are almost as ubiquitous as the voice, and they tend to be made of materials native to their place of origin. For instance, on islands from the Pacific to the Caribbean, conch shells have long been blown as trumpets; similarly, many instruments from coastal Africa and Southeast Asia were commonly decorated with small cowrie shells that washed ashore. Musical bows were widespread in the rain forest areas of Central and Southern Africa, likely adapted from hunting bows by peoples for whom hunting was a part of daily life. In Listening Guide 9, we hear the sound of the hunting bow, which is rich in overtones.

0:38 |

Date of recording: 1962 Performers: Dorsey Dixon Function: Sung to recall a historical event—a catastrophic train wreck—and to entertain |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The nasal quality of singer Dorsey Dixon’s voice

Beyond the close connection of musical instruments to the local ecology and economy, musical instruments reflect and embody the technologies of their time and place. Examples are numerous. Bronze metallurgy is known to have entered mainland areas of Southeast Asia by late in the second millennium before the Common Era; Vietnam was the site of the first bronze instruments (drums).5 Indonesia later developed large instrumental ensembles called gamelan, dominated by xylophones and gongs made of bronze (see Listening Guide 29, in Chapter 2).

In nineteenth-century Europe, the Industrial Revolution introduced new materials and techniques of mass production that transformed the construction of many musical instruments, incorporating steel wires and iron frames within the piano and fashioning new types of valves for wind instruments such as French horns. In early-twentieth-century Trinidad, instruments were made from everyday items such as soap boxes, biscuit tins, and bottles. During the 1930s, discarded fifty-five-gallon steel drums from the oil industry were modified into musical instruments that came to be known as “pans” or “steel drums.” Steel drums, which could be played alone or in groups, as heard in Listening Guide 10, subsequently spread throughout the Caribbean and beyond. While early in their history steel drums varied in their designs, in recent decades they have been manufactured in standardized forms, making it possible for a player to move from band to band without difficulty.6

0:43 |

Date of recording: 1957–58 Performers: Unidentified Mbuti musical bow player Function: For entertainment |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The rich sound emanating from the single string, producing both a fundamental and harmonics

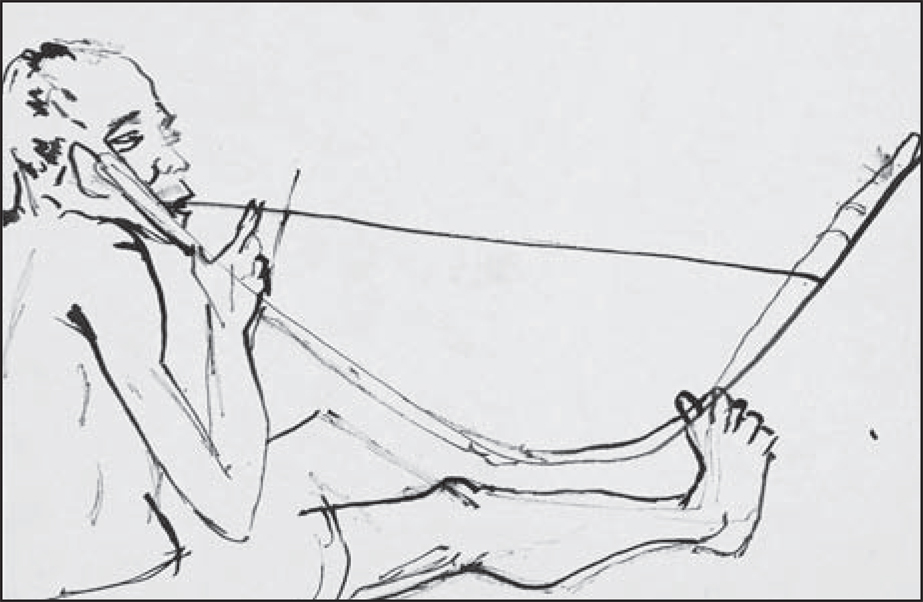

A musical bow player from the Ituri Forest in the northeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) anchors the bow with his right foot, and grasps the other end in his right hand. He strikes the string of the bow with a stick held in his left hand, and rests the top against his lips, allowing his mouth to serve as a resonator for the musical sound. Sometimes, a gourd is attached to one end of the musical bow and rests against the chest of the player to act as an external resonator.

Musical instruments are an important part of most societies’ material culture, a term anthropologists use to refer to objects used in everyday life. Instruments can carry powerful associations to the contexts within which they are played. For instance, the large gong that anchors the music of the Indonesian gamelan in ritual contexts has long been considered to have supernatural power. Instruments can also change functions and gain new associations over the course of time, as can be seen in the case of the Japanese bamboo flute, the shakuhachi, during the last thousand years. A millennium ago, musicians within the Japanese court first played the shakuhachi; later the instrument became a form of Japanese Buddhist musical expression.

The sound of some instrumental ensembles can over time come to represent the political entities by which they were organized and supported; these instruments can also be used in new contexts. For example, military bands, which were first established worldwide following the entry of European colonial powers into the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, are today ubiquitous in ceremonies, parades, and other events whenever national or military power is celebrated.

0:33 |

Date of recording: 1962 Performers: The Rise and Shine Steel Band Function: For dance accompaniment and entertainment |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Notice how steel drums originally used to store oil have been transformed, when empty, into resonant sound generators. The timbre and tone changes depending on where the player strikes the steel drum.

Members of the Despers USA Steel Orchestra practice for the West Indian Day parade in Brooklyn, New York. In this photograph, you can see the ovals tuned to individual pitches (named according to the Western scale) that are molded into the pan’s surface; the larger the oval, the lower the tone.

An example of a gong, an instrument of the traditional Indonesian gamelan orchestra.

The shakuhachi was played beginning in the Edo period (1603–1868) by komuso, wandering mendicant priests who wore wicker baskets over their heads to disguise their identities while working as spies for the government. While their organization was abolished in the Meiji Restoration, the twentieth century still saw wandering komuso on the streets of Tokyo.

In many societies, particular instruments are closely identified with either men or women. Horns and drums are often associated with men, particularly those of high rank and royal status. In African courts such as those of the Asante kings in Ghana, musicians playing trumpets and drums perform an important role within state ceremonies. The frame drum is used widely throughout the Middle East to accompany wedding music and remains closely associated with the female musicians who play it. In some places, women are formally or informally prohibited from playing certain instruments; women in Mongolian pastoral communities were historically prohibited from playing all instruments except for the jaw’s harp.7

Over time, instruments that are markers of ethnic and national identity can attain even deeper associations as people move beyond the boundaries of their historical homelands. One notable example is the Armenian duduk, a wind instrument played in the Armenian countryside, heard in Listening Guide 11 (see p. 37). The duduk’s sound has come to symbolize that country wherever individuals of Armenian descent live.

Instruments often carry prestige or status related to their historical roles in society. Those long associated with social elites, such as keyboard instruments in Europe, commanded respect and often were perceived to raise the status of those outside the elite who acquired and played them. In some places, a high-status instrument has a less prestigious equivalent within the same society, with corresponding differences in sound quality. Such a pairing is found in highland Ethiopia, where aristocrats of the Ethiopian court played the large, ten-stringed lyre (baganna), which they associated with King David, to accompany singing of psalms and hymns. Within the same region, professional musicians with low social status played a smaller and less elaborate six-stringed Ethiopian lyre (krar). The krar was known as “the devil’s instrument” because of the myth that it arose from the devil’s attempt to mimic the larger baganna. Instead of inspiring religious devotion, the sound of the krar is said to arouse emotions associated with carnal love or obscenity.8

An eight-holed, double-reed Armenian duduk. The wood binding attached by a string is placed over the mouthpiece to keep its reeds together.

This harp, made of ivory and okapi hide, was commissioned in the early colonial period by the Mangbetu Chief Okondo. The human figures on the neck of the instrument and the ivory pegs have elongated, wrapped heads that exemplify Mangbetu aesthetic ideals of the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. The figure on the instrument’s neck is that of a man, while the five pegs are topped with heads of women, identifiable by their fanlike coiffures.

0:33 |

Date of recording: 2002 Performers: Gevorg Dabaghyan and Grigor Takushian Function: For entertainment at parties and weddings |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The distinctive nasal quality of the two duduks, one of which plays a high melody while the second produces a continuous, lower line called a drone. Listen to the continuous sound of the drone, produced through a special playing technique called circular breathing, which is used on some wind instruments. The player breathes in through the nose while simultaneously blowing into the instrument through the mouth.

Musical instruments can also have substantial economic value. In many societies, instruments are richly decorated and used for purposes of display. Among the most beautiful instruments are those produced by the Mangbetu people of Zaire (now called Democratic Republic of the Congo), who carve their instruments from ivory and cover them with rare animal skins.

THE STUDY AND CLASSIFICATION OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

So striking are the sounds and shapes of musical instruments that they have long been avidly collected by travelers. By the late nineteenth century, this practice led to an international marketplace for musical instruments and also spurred the development of a new field called organology, the study of musical instruments. When European museums expanded their collections to include musical instruments from different places, the need arose for categorizing and comparing instruments. In 1914, Curt Sachs and Erich M. von Hornbostel published a four-part classification system based on the means by which instruments produce sound. What came to be known as the Sachs-Hornbostel system (later expanded to include instruments that generate sound electronically) today comprises five categories that accommodate most musical instruments in existence (see the Appendix).

IDIOPHONES The first of the five categories includes instruments that are self-sounding, that is, the material of which they are made, whether wood, metal, or another substance, is somehow set into vibration. These self-sounding instruments are called idiophones; they include gongs, bells, and your two hands and feet, which become idiophones when they are clapped together or stamped on the ground. Idiophones are divided into subcategories according to the manner in which the material is set into motion, such as by striking, shaking, scraping, or stamping. Steel drums are examples of struck idiophones (see Listening Guide 10), while rattles are shaken idiophones (see Listening Guide 21, in Chapter 2, and also figure on p. 2).

CHORDOPHONES String instruments, or chordophones, have one or more vibrating strings as the sound source. Chordophones are subdivided into four categories differentiated by shape: lute, harp, lyre, and zither. Lutes have a neck and body to which strings are parallel. The strings are attached to one end of the neck (usually by pegs) and are anchored on the body; the body of the lute is usually hollow and lends additional resonance. The Tuvan igil seen on page 4 of the Introduction is an excellent example of a long-necked lute; a similar Mongolian lute is heard accompanying the long song in Listening Guide 7. The guitar is one of the most widely distributed lutes worldwide.

SOUND SOURCES |

|

VOICES AND INSTRUMENTS

Although the Sachs-Hornbostel classification system is used all over the world in museums and by scholars, many societies have their own systems of categorization. In ancient China, for example, instruments were classified according to the materials from which instruments were made, including earth, stone, metal, skin, silk, wood, gourd, and bamboo. In European music, instruments were divided into three categories—strings, wind, and percussion—a system derived in part from the ancient Greeks. A scheme used by the sixth century in India anticipates the categories of Sachs-Hornbostel, incorporating “stretched” strings, “covered” drums, “hollow” winds and “solid” idiophones.9

There is no cross-cultural system used to classify voice types, although an early Indian treatise included the singing voice along with hand-clapping within the five categories of instruments. One ethnomusicologist proposed that the term “corpophones” be used for instruments that are part of the human body.10 Voices are sometimes named by their sound, as in the common Western designation of soprano, alto, tenor, and bass, or by the musical style they usually sing, such as opera singer, blues singer, or rapper.

Although instruments cover a wider range and variety of sounds than voices, there are frequently similarities between vocal and instrumental quality and style within a given soundscape. Particularly interesting are those traditions in which voices imitate instrumental sounds, as in the “mouth music” with which Scottish singers duplicate the sound of bagpipes, heard in Listening Guide 37 (see Chapter 3).

All lutes can be plucked with the fingers or a pick (plectrum), while others are played primarily with a bow. A well-known plucked lute is the North Indian sitar, heard in Listening Guide 12.

Harps have a soundboard to which strings are attached at an angle. The musical bow (see p. 34) is a good example of a single-string harp, the Celtic harp (see p. 28) a good example of an angular (triangular) one, while the Mangbetu harp (see p. 36) is a good example of an arched harp.

Lyres, which today survive only in East Africa and the African Horn (see Ethiopian baganna at left), have two distinctive arms extending up from the body and a crossbar running between; the strings are attached to the crossbar.

The zither has a flat body; the strings are attached parallel to the body. There are many zithers with rectangular-shaped bodies throughout East Asia, varying in size and number of strings. Zithers are designed to be plucked with a finger or plectrum and include the trapezoidal-shaped Egyptian qanun, popular throughout the Middle East (see Chapter 4), and the North American dulcimer.

This modern Ethiopian painting presents an Ethiopian emperor as King David playing the baganna, a popular image in Ethiopian art, derived from descriptions in the Book of Psalms. The instrument has a typical lyre structure with its two upright arms connected by a crossbar to which the ten strings are attached.

The sitar’s face is made of carved wood attached to a large gourd. In some styles of playing, another gourd is attached to the top of the instrument’s neck (pictured here). The number of strings varies according to the style of the sitar, and they have three basic purposes. The five main strings on the fingerboard of the instrument are used for the melody and can be pulled along the frets (small ridges of wood or metal) to produce large slides and subtle ornaments. Two thinner strings called chikari are used for rhythmic punctuation, and the majority of the instrument’s strings (attached to smaller tuning pegs running along the side of the instrument) are “sympathetic strings,” vibrating with the main melody. These sympathetic strings, along with the instrument’s special flat bridge, which raises the strings above the face of the instrument, give the sitar its uniquely metallic, resonant sound.

AEROPHONES Aerophones are instruments in which an enclosed column of air vibrates to produce sound, such as flutes, trumpets, and horns. The size and shape of the inside of the instrument, termed its bore, determines the range of harmonics produced, and in part shapes each instrument’s distinctive tone quality. Aerophones have an opening, or mouthpiece, through which the player blows air. The distinctive aerophone from Australia, the didjeridu, is blown through a hole at the end (end-blown), in contrast to many flutes, which are blown through a mouthpiece on the side (transverse). The didjeridu produces a drone consisting of a fundamental and one or more harmonics. The instrument is used primarily to accompany songs, and is almost always accompanied by wooden clapsticks, as heard in Listening Guide 13.

1:49 |

Date of recording: 1967 Performers: Ustad Vilayat Khan Function: Demonstration recording |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The resonance of the strings as they are plucked with a wire plectrum called a mizrab, setting into motion the sympathetic strings that resonate in the background

The didjeridu, made of a hollowed-out log, may be large enough to require the help of a second musician to support the instrument.

In contrast to the open end of the hollowed-out log that constitutes the mouthpiece of the didjeridu, aerophones such as the European clarinet and the Armenian duduk have mouthpieces holding reeds that give each instrument its distinctive tone quality. The reed, which may be made of natural cane or of a synthetic material, is a small rectangular piece held between the lips; it vibrates as it channels the player’s breath into the instrument.

Instruments are termed single- or double-reed aerophones, depending on the number of reeds used; the clarinet is a single-reed instrument, while the duduk has two reeds. The single reed vibrates against the mouthpiece of the instrument while double reeds vibrate against each other.

Instruments that have enclosed reeds through which air is pushed, such as those within the bagpipe, are classified as free reed aerophones (see Chapter 3, “Sound Sources: The Scottish Highland Bagpipe,” p. 143). Finally, there are a few aerophones that act directly on surrounding air without enclosing it, called free aerophones. An example is the Australian bull roarer, a thin board attached to a string that produces a roaring sound when whirled above the player’s head.

MEMBRANOPHONES Membranophones, popularly known as drums, constitute the fourth category of musical instruments. Membranophones are characterized by a membrane (drumhead) stretched across one or both ends of the instrument. Membranophones are classified according to their shapes, which may be cylindrical, bowl (kettle), hourglass, or goblet; according to the ways in which the heads are attached to the body of the instrument (glued, tacked, laced, etc.); and according to the ways in which the drumheads are made to sound (by hands or sticks). The sabar drum, played by professional musicians in Senegal, is a single-headed drum that uses a combination of hand and stick strokes to produce a variety of sounds. The stick is usually held in the right hand, while the left hand hits the drumhead directly. Listening Guide 14 (see p. 42) demonstrates the variety of sounds played on the sabar (see p. 53).

ELECTROPHONES The fifth and final category of musical instruments, electrophones, was added in the mid-twentieth century in order to include instruments whose sound is produced or modified electronically, such as the synthesizer or the electric guitar. Instruments such as the electric guitar overlap the chordophone and electrophone categories.

1:02 |

Date of recording: 1998 Performers: Didjeridu and clapsticks accompanying Alan Maralung (voice) Function: Wangga song performed for rituals and for entertainment |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The ways in which the player enhances the didjeridu’s distinctive tone quality by vibrating his lips and resonating the sound in his mouth. The player sustains an unbroken tone by using circular breathing.

The Sachs-Hornbostel classification is provided in detail in the Appendix. The system is useful when discussing instruments from a comparative perspective, enabling one to identify structural similarities in instruments with different names from different places; it also helps to distinguish between instruments that have similar names but are constructed differently and hence produce different sounds. The human voice is not included within the Sachs-Hornbostel classification system, although it can be said to conform most closely to the aerophone category, with an enclosed column of air setting the vocal cords into vibration.

0:24 |

Date of recording: 2003 Performers: Lamine Touré Function: Named rhythmic pattern (bàkk) played on the sabar drums in contexts ranging from lifecycle rituals to nightclubs |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The rhythm, named Lenëën bàkk, first “spoken” by the drummer (transcribed below) and then “drummed.” Each of the syllables represents a different stroke. Three basic hand strokes are represented by “gin,” “pin,” and “pax,” while the other syllables specify different strokes by the stick, some in combination with the hand. “Ja,” for example, means that the stick hits the skin and bounces off freely.11 This rhythm is associated with the Mbaye family of Kaolack and Dakar, Senegal.

TEXT

Te tan pax gin, te tan pax gin chaw ra jan pax, gin jan pax, ja pa ja gin gin jan jan pax gin, / te tan pax, gi gin, te tan pax gin . . . raw raw ran gin gin

Sabar drummers accompany dancing for the enjoyment of all during the Senegalese tanibeer, a convivial celebration of Wolof people in a neighborhood in Senegal’s capital city, Dakar.

INTENSITY

Closely related to the quality of instruments and voices is intensity—the loudness or softness of a sound. Intensity, often referred to as volume or dynamics, is a vital part of the listening experience. Certain musical instruments, such as many types of bagpipes, were originally constructed for outdoor performance; their construction ensures a high level of intensity and the instruments can be heard over considerable distances, but they are unable to vary the intensity level. Some vocal styles, such as Swiss yodeling, are also outdoor styles, as was harmonic singing in the lives of Tuvans and Mongolians. When a large number of instrumentalists or singers perform together, great contrasts in volume are possible. The intensity of a sound is also deeply linked to its cultural setting and function: a woman singing a lullaby while rocking her baby to sleep obviously sings at a lower volume level than when leading her church choir in the performance of a hymn.

Although the loudness or softness of music can be measured precisely by a decibel meter, the human ear cannot quantify intensity in the same way. However, the ear and body are quick to sense changes in intensity and to perceive relative levels of loud and soft sounds. Many music traditions have terms to describe different levels of intensity, and some incorporate more contrasts of soft and loud sounds than do others. Clear examples of changing intensity levels can be heard within the Balinese instrumental (gamelan) tradition, which employs a wide range of terms drawn from the Indonesian and Balinese languages to describe different dynamics. A strong, loud sound is keras, while its opposite is manis (sweet, soft); a neutral intensity level in between these two poles is termed sedeng (average). Gamelan musicians also refer to increases (nguncab) and decreases (ngisep) in intensity.12 Contrasting and changing intensity levels can be heard in the Balinese gamelan music in Listening Guide 29, Chapter 2.

One finds similar attention to dynamics in Western classical music, which uses the Italian words forte and piano to refer to loud and soft sounds, respectively. Each of these terms can be further modified—mezzo forte (moderately loud), fortissimo (very loud)—to differentiate further levels of dynamic contrast. Musicians also use the terms crescendo and decrescendo to refer to an increase or decrease in volume. The term sforzando indicates a sudden loud sound.

The relative volume level, or changes in volume, can reflect deeply held emotional or affective values within a music tradition. For instance, Balinese musicians associate dynamics with rasa (feeling, expression) in their music, believing that changing dynamics enhance the structure of the music and convey feelings such as strength, sweetness, or softness, as noted earlier.13

The widespread use of amplification has reshaped perceptions of intensity within many music traditions. Performers (or sound technicians) often adjust the volume level during live performances as well as during recording sessions. Even the casual listener can reshape intensity by manipulating the volume control on her radio, iPod, or MP3 player. It is therefore important to consider the potential impact of amplification during any listening experience.

PITCH

The fundamental of the harmonic series vibrates at a specific frequency, a faster vibration producing a higher sound and a slower vibration producing a lower sound. The relative highness or lowness of the sound is known as pitch.

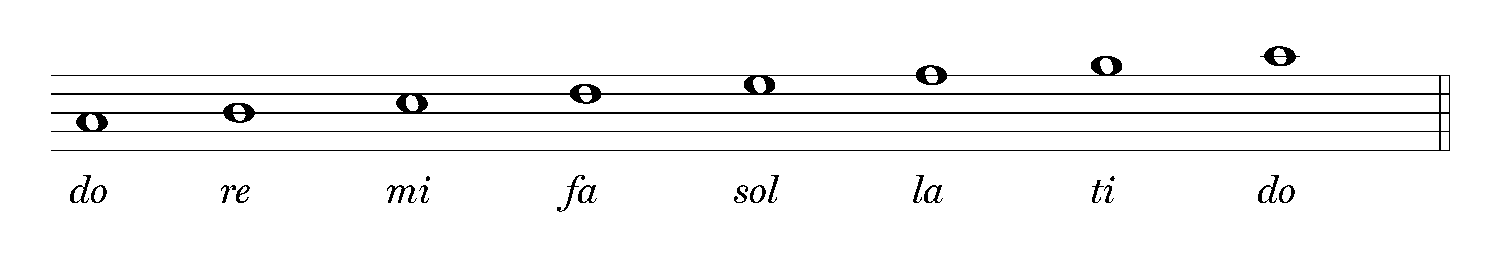

When the frequency of the fundamental is doubled, the ear perceives the sound as the same pitch class, but at a higher level, called an octave. When the frequency is halved, the pitch is perceived to drop an octave. Put differently, when a low voice and a high voice sing the same tune, they sing the same pitch classes, but an octave or two apart. This set of equivalent pitches at the distance of an octave is an acoustical phenomenon recognized in many, but not all, music traditions, although it is called by different names. The Western classical tradition uses syllables known as solfège to name pitch classes, as illustrated in the figure below.

This figure shows the syllables used to represent pitch classes in Western music traditions. The fundamental is do, which recurs an octave higher.

HEARING AND COMPARING PITCH SYSTEMS AND SCALES

Each voice and instrument can produce only a certain number of pitches, some more comfortably than others. The overall compass of pitches from the highest to the lowest that an instrument or voice can produce is termed its range. Apart from the physical capability of a sound source to produce sounds throughout its range and its greater comfort in certain areas (registers) within that range, music traditions inevitably select particular sets of pitches for regular use.

Many music traditions are sung and played at a pitch level comfortable for the singers or instrumentalists, just as we start a tune on any pitch that is convenient. More important are the distances between pitches, which are called intervals. The size and arrangement of these intervals, and the resulting relationships among pitches, vary greatly among music systems. Listeners accustomed to one music system often perceive a different set of intervals in an unfamiliar music tradition as sounding “out of tune.”

Many music systems have their own special terms for describing and prescribing the set of pitches they use, and, by extension, the relationship between any two adjacent pitches. The classical music of North India, for example, organizes its music according to ragas, groupings of certain pitches and intervals that move in characteristic patterns. If we return to Listening Guide 12, a sitar performing Rag Des (pronounced “Rog Desh”), we can hear that the music uses a distinctive set of intervals. While North Indian ragas are also much more than just distinctive assortments of pitches (each raga is named and has characteristic melodic movements as well as other associations, as we will see in Chapter 3), here we will discuss only the pitch content.

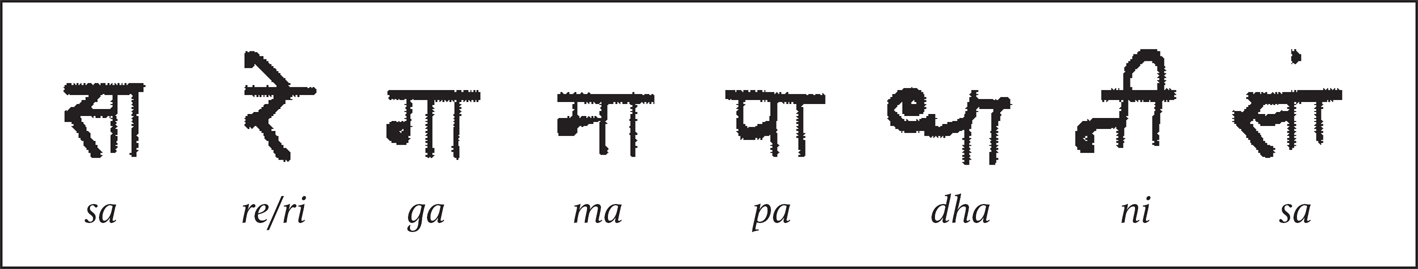

In order to summarize the set of pitches that constitute a particular raga (or another music system), musicians commonly arrange all the pitches in order of ascent and descent, called a scale. The scale is a concept taken from Western classical music that has been adopted and adapted by many other music traditions in the course of the last century or two. This is true of India, where the pitch content of a raga is often represented by syllables widely used for teaching, singing, and writing down melodies, termed sargam. This system of representing pitch, similar to Western solfège, provides names for the seven most important tones in the Indian scale, moving from the lowest to the highest, as shown in the figure below.

Listen closely to the pitch content of Rag Des, which varies as the melody ascends and descends. The most important pitch, or tonic note, Sa, is easy to hear, since it is reinforced by a drone. The pitch Ni is inflected differently in this raga, depending on whether the melody is ascending or descending. The musician plays Ni slightly higher and repeats it three times as the melody first ascends to the upper Sa, but plays it lower as the scale descends.14

The Indian system of solfège, called sargam, is named after its first four notes, “sa re ga ma.” It is presented here in both its English transliteration and in Devanagari, the script in which Sanskrit, Hindi, and several regional languages are written.

Mode is a flexible term that can refer, depending on the context, to the general pitch organization of a music tradition or to a particular scale of pitches. Scholars have also sometimes categorized the pitch resources of a given music culture by the number of pitches used. For example, pentatonic scales, with five pitches, are quite common in many cultures, although the intervals between the pitches may vary between traditions.

In many traditions, such as the Western and Indian classical traditions, some pitches are perceived as more important than others and serve as points of departure or arrival, especially at the beginning and end of melodies. We should be aware, however, that in some music traditions the individual pitches used are not conceived as separate entities, nor are they named; we will encounter one such example in our study of Ethiopian sacred music in Chapter 8. Other traditions have no special vocabulary for describing pitch, or so far, study of the music system has not documented this information.

The pitches of the Western music system can most easily be understood by looking at a piano keyboard, in which each octave is divided into twelve pitches an equal distance apart. Each pitch is sounded by pressing a white or black key. The seven white keys have letter names and are arranged in the order C–D–E–F–G–A–B. A black key can be called by the letter name of either adjacent white key, along with the sign of a sharp (#) or a flat (Ƅ): the black key between C and D can be named C sharp or D flat, depending on the musical context. Each of the twelve keys in the octave can serve as the lowest tone of seven pitches that is a scale. These scales are the basis for the musical language of Western music. Because it is cumbersome to use the names for pitches based on any single music system, ethnomusicologists have developed a system called “cents” to quantify the measurement of intervals and facilitate comparison. The cents system assigns the octave the total value of 1,200 cents and then divides it into twelve equidistant intervals following those of the modern Western scale, each equaling 100 cents. This method measures the frequency of pitches used in different music systems and converts the distance between them into cents, providing a useful tool to define pitch content and interval size in comparison to those in Western music.

MELODY AND PROCESSES OF ORNAMENTATION

Most music traditions organize pitches into meaningful units, termed melody. A melody orders pitches in distinctive patterns that are perceived to have a beginning, middle, and end. Some traditions use relatively few pitches and tend to have melodies with a narrow range, such as the Australian wangga song heard in Listening Guide 13. Return to that example now and listen closely to the voice part, which sings the melody. The short melody begins with a number of repeated pitches and then descends to end at a lower pitch. The motion of this melody can be termed conjunct—that is, it moves in close and regular intervals in a stepwise pattern.

Other music systems use a large number of pitches, resulting in melodies with wider ranges. A melody can encompass different numbers of pitches and often does not use all pitches available within a single vocal or instrumental part. As an example, return to Listening Guide 7, and listen again to the vocal melody of the Mongolian long song. In contrast to the Australian wangga song, the melody of the long song has a very wide range; it both ascends and descends. The long song melody moves mainly in larger intervals, which is termed disjunct motion; notice especially the leap of more than an octave at 0:39.

Melodies can be decorated or ornamented in a variety of ways. A good example is found in the Mongolian long song (Listening Guide 7), where the singer uses trills, a fast movement between two adjacent pitches, heard at 0:15, 0:20, and intermittently throughout the excerpt.

There are names for different kinds of ornaments within most music traditions. For example, North Indian music uses a wide variety of ornaments, most of which are named. In Rag Des (Listening Guide 12) the most important ornament is the mind (pronounced “meend”), a slow slide from one tone to another.15 The mind is crucial to establishing Rag Des’s identity, particularly when it occurs on the ascent from Re to Ma and on the descent from Ga to Re. The slide from Ga to Re is heard near the beginning of the sitar melody, and again in three different octaves at 1:00 (upper), 1:10 (middle), and 1:12 (lower). Near the end of the melody, the two minds (Re to Ma and Ga to Re) are joined together and emphasized from 1:27 to 1:34. A mind is the final sound heard at 1:43.

Melodies are made up of phrases. Here musical terminology borrows from language: musical phrases, like phrases in speech, carry an idea or thought but do not constitute a full sentence.

Filigree decoration on jewelry provides a parallel to ornamentation of a melody.

When melodies are sung, they can extend to the very boundaries of the breath and challenge a singer’s endurance; listen to the phrase in the Mongolian long song beginning at 0:24, which is so extended that the singer must grab a quick breath before the sudden ascent at 0:37 in order to sustain the phrase to its end at 0:47. Conversely, phrases can be short, as heard in Listening Guide 10, where the steel drums play a melody over and over with some slight variations. The steel drum melody subdivides into two phrases of equal length, the second phrase mimics the first at a slightly lower pitch.

Musical phrases are not always symmetrical. For instance, listen again to the Senegalese sabar bàkk presented in Listening Guide 14, in which the drummer speaks the bàkk against a background of twelve tapped beats and then plays the bàkk on the sabar drum. The bàkk is divided into two main parts of unequal length, marked in the drum syllables by a slash. The sabar example also leads us beyond the boundaries of pitch organization to consider the manner in which time is organized.

DURATION

Just as music organizes pitch, it also shapes time. When we listen to music, we enter a time continuum different from that of nonmusical experience. We talk about duration by using the terms pulse (a regular beat, such as the heartbeat), which produces rhythms (patterns arising from different combinations of beats). We can also use the term rhythm in a broader sense to refer to the general temporal organization of music.

Music’s rate of speed or pace, called tempo in Western music, is specified (like dynamics) by a variety of terms in different music cultures. Western classical music uses Italian terms, ranging from adagio (slow), to andante (moderate), and allegro (fast). The music of the Balinese gamelan gong kebyar, heard in Listening Guide 29, emphasizes changes in pace and has its own terminology.

HEARING AND COMPARING DURATIONAL SYSTEMS

The durational aspects of sound can be regular, irregular, or free.

Regular rhythms are quite common in many music traditions; note the strong pulse maintained in the Inuit katajjaq heard in Listening Guide 6. Similarly, in the Australian wangga song in Listening Guide 13, the clapsticks enter at 0:19 with three sharp strokes and then establish a regular beat.

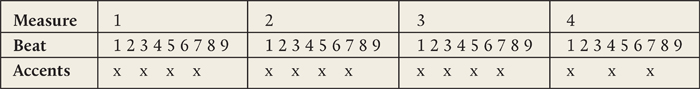

Much of Western classical and popular music has a regular pulse, organized within a hierarchical durational system called meter. Meter subdivides music into groupings of two, three, and four beats, each grouping called a measure. We name these simple meters according to the number of beats in each measure, terming them duple, triple, or quadruple meters, respectively.

Simple meters are used in many types of music, ranging from symphonies to pop tunes, and are familiar to you from casual listening. For instance, duple meter is commonly heard in marches; each footstep corresponds to one beat, the right foot emphasizing the first beat of each two-beat measure. Emphasis or stress on a beat is termed an accent, which often reinforces the first beat of every measure.

The waltz, a well-known ballroom dance, is always set in a triple meter. Most music for social dancing usually has regular rhythmic patterns that help partners or groups synchronize their movements, as we will see in a study of tango in Chapter 7.

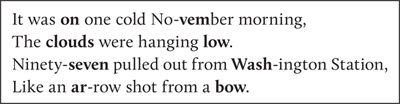

The American folk song Wreck of the Old 97, heard in Listening Guide 8, is an example of quadruple meter; each verse of the song lasts eight measures for a total of thirty-two beats. The otherwise regular quadruple meter is lent more variety by the voice beginning on the last beat of the instrumental introduction, which results in word and verse divisions overlapping the measure boundaries, as seen in the following.

Bold typeface marks where the first beat of each quadruple [four-beat] measure falls in the first verse of Wreck of the Old 97. Note that the first two words of the verse (“It was”) are sung on the last beat of the introduction.

Duple, triple, and quadruple meters can be multiplied by three to produce compound meters of six, nine, or twelve beats per measure. Groupings of five, seven, and nine beats are found in many music cultures.

We will begin to explore the ways in which music traditions organize rhythm later in this chapter when we discuss time organization within a Middle Eastern instrumental piece in Listening Guide 19 (see p. 58). Here it is important to emphasize that while the term meter is of European origin, many music traditions have their own ways of using and naming regular groupings of beats. The length of these regular rhythmic patterns can vary. For instance, the steel band music in Listening Guide 10 has a melody that is eight beats long, subdivided into two four-beat phrases.

It is also possible to have a regular beat reinforced by different rhythms in different voices or instruments. Listen to Time (see Listening Guide 15), a song describing Judgment Day, performed by men who used to work together on boats gathering sponges off the shore of the Bahamas. Insiders call Time a rhyming spiritual because of the close coordination between the lead singer, who performs fast couplets, with the chorus, which accompanies him with a repeated verse. The song has a strong quadruple meter with an accent on the first beat of each measure.

1:02 |

Date of recording: 1998 Performers: Men from Andros Island, led by David “Pappie” Pryor Function: Performed by men working in the Bahamian sponging industry and at wakes |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The four-beat (quadruple) rhythmic patterns strongly outlined, with an accent on the first beat, in the low (bass) and high (tenor) male parts by the chorus (called bassers) singing the word “time.” All support a rotating lead singer (called the rhymer), who performs a text above the chorus at approximately double the rate of speed. Listen to how the fast solo part overlaps and falls between the four beats of the chorus parts.

TEXT |

|||

|

Sinner man, then you need not dwell, |

O way over yonder, |

|

|

O you countin’ your finger, |

O one of these mornin’, |

|

Contrast the regular meter of Time with the rhythmic asymmetry of the jazz piece heard in Listening Guide 16 (see p. 50). In this famous composition by Dave Brubeck, we hear a fast, nine-beat rhythm repeated four times to constitute a four-measure grouping. In the first three measures, the nine beats are subdivided as 1-2/1-2/1-2/1-2-3. In the fourth measure, Brubeck subdivides the nine beats differently as 1-2-3/1-2-3/1-2-3. Brubeck borrows this nine-beat rhythm from a popular Turkish dance rhythm known as karsilana (pronounced “KARSH-ee-lana”). The sudden change in the rhythmic subdivision of the fourth measure interrupts the established accents and introduces an unsettling effect termed syncopation. Syncopation can occur by accenting an unexpected beat or changing subdivisions within a regular meter without changing the number of beats, as in this example, or by adding or subtracting beats from an ongoing regular meter, thereby changing the number of beats in a measure.

The traditional occupation of sponge fishing, practiced by the singers from Andros Island heard in Listening Guide 15, was captured in an 1885 watercolor, Sponge Fishing—The Bahamas, by Winslow Homer (1836–1910).

Many music traditions use irregular or asymmetrical meters. Listen again to the Mbuti musical bow in Listening Guide 9, which repeats similar phrases that contract and expand, each phrase incorporating a different number of beats.

Some music is so flexible in its rhythmic organization that it may be said to have free rhythm. Listen again to Listening Guide 12, Rag Des, which has a flexible rhythmic framework without a steady pulse. The sitar player lingers over the melody, prolonging some pitches, shortening others, and pausing in between phrases. Both the long song in Listening Guide 7 and the duduk music in Listening Guide 11 also exhibit free rhythm.

1:21 |

Date: Recording released 1959 Performers: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, with Dave Brubeck, piano; Paul Desmond, alto saxophone; Eugene Wright, double bass; and Joe Morello, drum set From: First section of longer composition containing eight repetitions of a 36-beat phrase Function: Jazz tune for listening |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Nine beats in each measure, repeated in four-measure groupings, setting up the feeling of a fast and repetitive rhythmic cycle

• Syncopation within each cycle. The first three measures of the cycle are subdivided as 1-2/1-2/1-2/1-2-3. See accents in chart below

• Changes in melody and chords between repetitions of the rhythmic cycles provide a sense of variation

Rhythm Structure for One Four-Measure Cycle (transcribed from rhythmic cycle 2 as played by the entire quartet):

STRUCTURE |

DESCRIPTION |

|

0:00 |

Rhythmic cycle 1 |

Piano solo. |

0:06 |

Rhythmic cycle 2 |

Bass and drummer enter. Bass reiterates same note on accent, called a pedal point; drummer accents first beat of measure 4 on cymbal. |

0:11 |

Rhythmic cycles 3 and 4 |

Saxophone enters playing melody at a higher pitch; piano and bass continue; drummer plays accents with cymbals, and adds other drums in fourth measure of cycle. |

0:23 |

Rhythmic cycles 5 and 6 |

Saxophone exits, piano resumes melody. Bass continues pedal point; drummer accents with cymbal and fills in with other drums. |

0:34 |

Rhythmic cycles 7 and 8 |

Piano part slightly varied, accompanied by bass and drums. Saxophone absent. |

0:45 |

Rhythmic cycles 9 and 10 |

Saxophone plays melody while piano, bass, and drums accompany. Strikes on various places on cymbal produce different sounds. |

0:56 |

Rhythmic cycles 11 and 12 |

Saxophone exits, reducing melody to one repeated pitch accented on piano, with piano chord on beats in-between accents. This further increases rhythmic complexity. |

1:07 |

Rhythmic cycles 13 and 14 |

Saxophone enters again with melody, whole quartet repeats cycle as in beginning. |

1:17 |

|

Fade-out. |