CASE STUDY: BOSTON, U.S.A.

WHY BOSTON?

Having surveyed the complex and distinctive settings for musical life in Accra and Mumbai, we will now take a more nuanced look at a city closer to home—Boston. One of the oldest cities in North America, Boston provides both a long history and exceptional ethnic, institutional, and musical diversity (see “Looking Back: A Boston Retrospective,” p. 88).

Boston provides a stimulating counterpoint to Accra and Mumbai; all three are ports, and all three still show the impact of British influence. But Boston is also a quintessentially American city, and its idiosyncrasies have imprinted themselves on its musical life.

Music was not always Boston’s primary artistic concern. Its first preoccupation, as noted in a biography of the Boston composer Amy Beach, was with “the word, as taught at Harvard and as preached from Boston’s pulpits.” 16 Only in the nineteenth century did music flower in Boston, thanks to the conviction among upper-class Bostonians that music had the power to uplift, educate, and refine.

Much of Boston’s documented musical life in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries involved an elite in close contact with England and Europe. Major ensembles that are still prominent, such as the Boston Symphony Orchestra, were established during that time. Understanding the background of musical life in Boston is important not just to unraveling local soundscapes, but also to appreciating Boston’s nineteenth-century role in making Western European music and culture prestigious throughout the rest of the United States. Boston is an important springboard for the study of local musics because it exercised so much influence on national musical life in the United States at an early date.

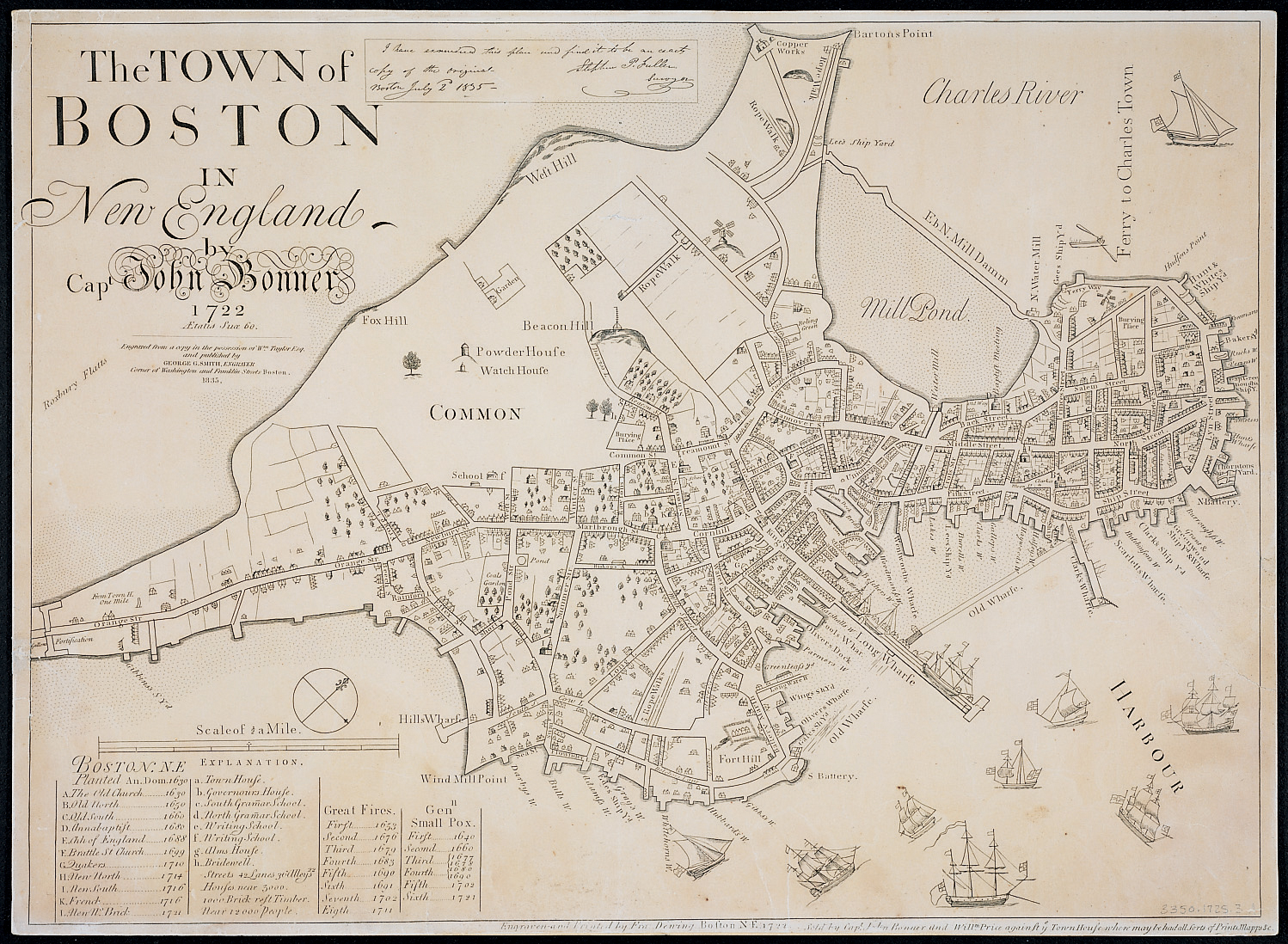

This early map of Boston shows landmarks that have not survived such as Mill Pond, as well as those that have, including the Common, Beacon Hill, and Long Wharf.

Boston’s distinctive physical setting in many ways gives rise to its musical profile. Founded in the seventeenth century, the city is bounded by the Charles River and Boston Harbor. Boston’s irregular, winding, narrow streets are similar to those of an English town. Boston’s setting is crucial to its cultural life.17

The old central area of Boston, known as Beacon Hill, sits alongside the distinctive, five-sided Boston Common and Public Garden, the city’s public heart since earliest times. Beacon Hill still retains historic cobblestone streets lit by gaslights and is located on the only one of Boston’s hills to survive; the others were leveled in the nineteenth century to provide landfill in the Charles River to create the section of the city referred to as Back Bay. (Interestingly, Mumbai also has a “Back Bay” area that was reclaimed from the ocean by landfill.) Other distinctive neighborhoods abound within the city limits, some with names that do not reflect their actual locations in relation to the central Commons and Public Garden—for example, the South End is not south of the city, nor is the North End north.

Along with their special locales, architectural features, and landmarks, many neighborhoods are home to different socioeconomic and ethnic groups. Boston’s population, totaling over 600,000 for the city and around 4.5 million for the larger metropolitan area, has shifted in its composition in recent decades. The 2000 census showed that for the first time, former minorities within the longtime mainly Euro-American population of the city became the majority. These changes stem primarily from a surge in immigration; the Latino and Asian communities have increased in size, now totaling 17.6 percent and 8.9 percent of the city of Boston population, respectively. A recent influx of new immigrants from Haiti, Jamaica, and Africa has joined longtime African American residents; almost 25 percent of Bostonians now identify themselves as “black.” 18

LOOKING BACK |

|

A BOSTON RETROSPECTIVE |

Incorporating multiple ethnic populations:

1630 English colonists from Salem, Massachusetts, found the city of Boston

1790 Haitian immigrants flee to Boston as a result of revolt against French government in Haiti and establish a French-speaking community

1847 37,000 Irish immigrants come to Boston as a result of famine in Ireland

1870 Portuguese immigrants begin to arrive in Boston

1900 Mass immigration of Italians to US; 31,000 in Boston by 1910

1990–2015 Soaring minority populations (including Vietnamese, Indians, Koreans, Mexicans, Columbians, Salvadorans, and Dominicans) transform the city of Boston into a “majority-minority” urban core with several increasingly multiethnic satellite cities

Founding major educational institutions:

1636 Harvard University

1852 Tufts University

1861 Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

1864 Boston College

1867 New England Conservatory of Music

1869 Boston University

1898 Northeastern University

1945 Berklee College of Music (as Schillinger House)

1948 Brandeis University

Making Boston more musical:

1838 Boston public schools incorporate music into curriculum

1881 Boston Symphony Orchestra’s inaugural concert

1885 Boston Pops founded

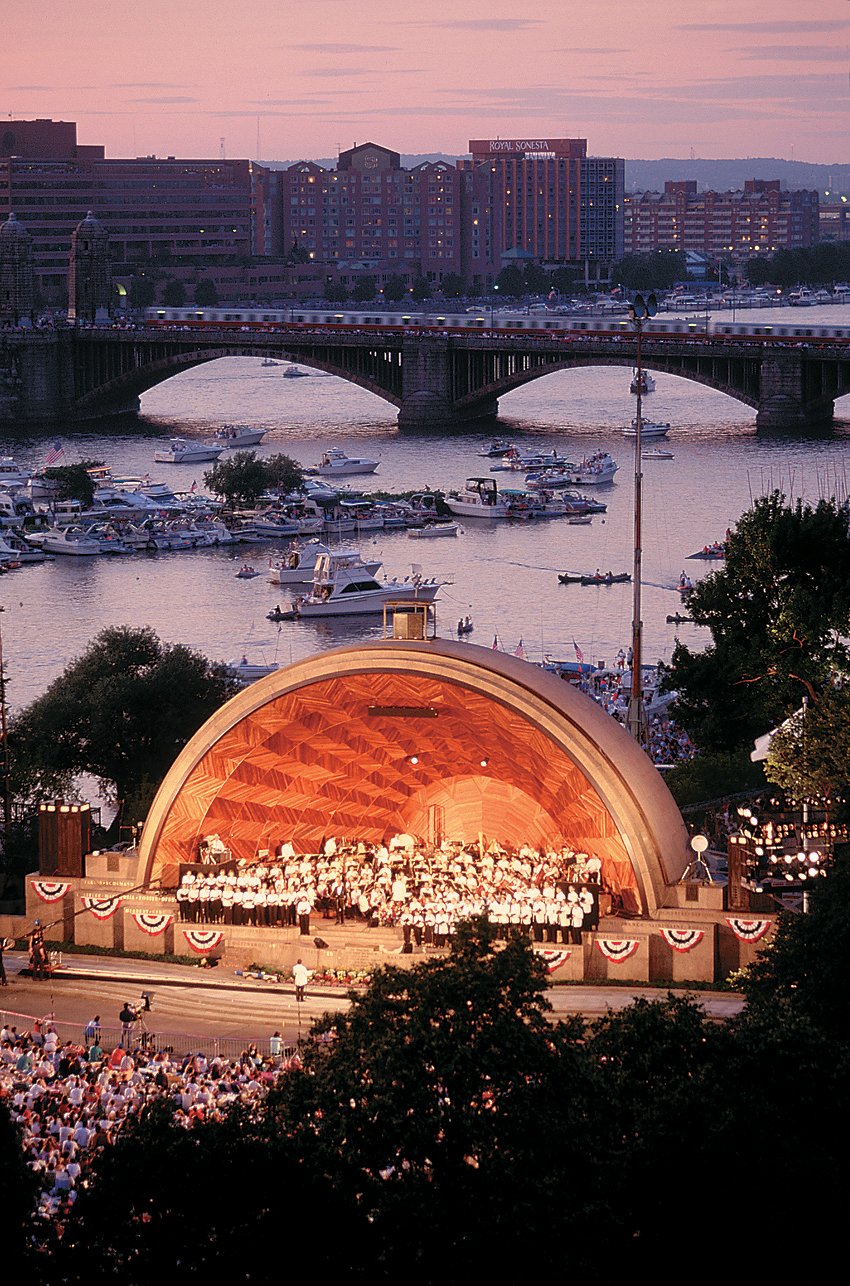

1929 Arthur Fiedler starts the Esplanade Concerts, a summer series held on the east bank of the Charles River

1954 Boston Camerata

1969 Club 47 becomes Club Passim

1979 Boston Village Gamelan (Javanese)

1981 Boston Early Music Festival and Exhibition

1990 World Music presents world music concerts

1993 Gamelan Galak Tika (Balinese)

1996 Boston Modern Orchestra Project

2006 New building of Institute of Contemporary Arts, with free “Harborwalk Sounds” concert series, featuring Berklee College jazz, pop, and world musicians

A multicultural mixture of peoples from all over the world has transformed and gentrified the South End, once a working-class neighborhood. At the same time, South Boston retains many Irish Americans, Roxbury remains heavily African American, and the colonial buildings of the North End still house longtime Italian residents. Moving from Boston proper across the river to Cambridge, we find a uniquely diverse population, reflecting the town’s role as the main center for higher education in a metropolitan area that has more institutions of higher learning than any other North American city and more students than any other place of comparable size. We will return later to this important aspect of Boston area life. Other towns adjacent to Boston include Chelsea and Charlestown, as well as nearby Brookline and Newton, each with its own distinctive topography, architecture, and increasingly diverse population.

This aerial shot is a bird’s-eye view of the banks of the Charles River, transformed into a performance space called the Esplanade. At the center of the space is the Hatch Shell, an open-air concert site that was restored and renovated for its fiftieth birthday in 1991. Free performances such as the annual July 4 celebration by the Boston Pops (shown here) are enjoyed by thousands, some listening from boats anchored on the river. The July 4 performance features patriotic choral works, rousing marches, and Tchaikovsky’s famous 1812 Overture enhanced by bells from the nearby Church of the Advent and the firing of howitzers.

Boston can be divided according to political boundaries and, to an extent, by economic and ethnic groups, but we can also map the city according to past and present locations of musical life. By 1910, one block of downtown Boylston Street housed so many of Boston’s piano dealers, instrument shops, music publishers, and phonograph sellers that it became known as “Piano Row.” 19 Some musical monuments are actually noted on street signs. Adjacent to Symphony Hall, the home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, is Symphony Road. Nearby is Opera Place, the former site of Boston’s original opera house, built in 1908 but torn down in 1958. The present-day Opera House was constructed in 1928 as a grand vaudeville theater. Opera performances were presented from only from 1978 until 1991. In 2004, Clear Channel Communications purchased and restored the Opera House as part of an effort to revitalize the downtown theater district.20

By way of introduction, we can begin to map aspects of Boston’s musical life that are not recorded on street signs. We will also see how an investigation of local music in Boston increases our understanding of what makes this particular urban area unique. We can start by asking what makes up Boston’s musical life, where is music performed, when is music heard, who makes music, and why?

WHAT ELEMENTS MAKE UP BOSTON’S MUSICAL LIFE?

We can get a general overview of musical life in any city through a quick look at the listings in a metropolitan newspaper. The Boston Globe, which has covered musical events in Boston since its founding in March 1872, has a daily arts section that is a good place to start mapping current musical events.

While print versions of local newspapers are useful for background on current musical events, newspaper-sponsored websites are becoming the most reliable sources for comprehensive listings. The Boston Globe’s website lists all arts events across the metropolitan area, with performances indexed by musical type, date, venues, and performers in alphabetical order. Categories include not just major rubrics such as pop, rock, classical, folk and traditional, jazz, world, and country, but an expanded list with a total of forty-two other types of music spanning the widest range of styles. The listing on the paper’s website includes more than a thousand musical events for just about any date, and can be sorted by towns in the metropolitan area, by artist name, by date and time, along with information about which events are ticketed and/or recommended. Another major source is ArtsBoston, which lists twenty-one categories of musical events.

When reading about Boston’s musical life, someone unfamiliar with the city could miss a number of important things. For example, there is no special topic on The Boston Globe list for the Early Music concerts that have for decades been a lively and distinctive aspect of the Boston music scene; ArtsBoston, in contrast, has listings for both Early Music and for Baroque Music, each containing multiple entries. For some other musical traditions, such as reggae and various Caribbean musical styles, one would have to dig deep into the sub-list to realize that Boston, after New York, is the largest reggae market in the United States.21

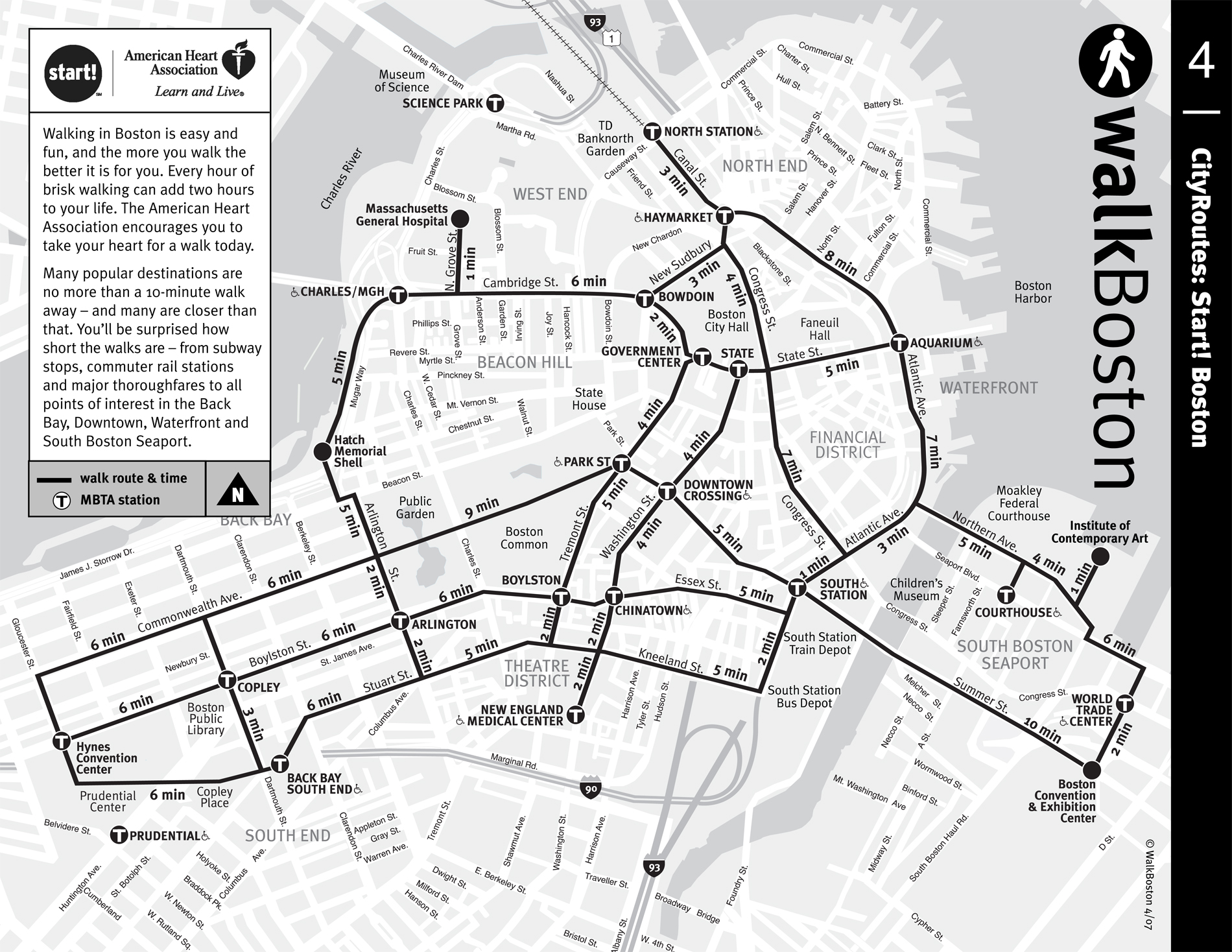

With its relatively compact size and many winding, narrow streets, Boston is best experienced on foot. The completion of the massive “Big Dig” construction project, which has relocated former surface highways underground, has resulted in new parks and public spaces, notably the 1.5-mile long Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. These settings will undoubtedly have an impact on urban musical life.

Boston’s many street musicians provide rich material for local humorists.

It is clear that newspaper and web listings provide only a partial map of Boston’s active musical scene. Large free festivals are included, but often not smaller music events sponsored by neighborhood or ethnic organizations. To uncover the extraordinary range of music available in Boston, we need to ask where else we should look for information, and we may need to walk or drive through town with our ears and eyes open for signs of musicmaking.

WHERE AND WHEN IS MUSIC PERFORMED?

Many soundscapes are associated with particular places and specific times. For example, the Boston Symphony Orchestra performs most evenings at its majestic Symphony Hall, at the corner of Huntington Street and Massachusetts Avenue.

Boston has many other well-known performance spaces, such as Jordan Hall at the New England Conservatory, most of which not only serve their own resident ensembles but are also rented out regularly to a variety of other performing groups. Even Symphony Hall is host to a wide array of musical events, particularly during the summer months. Other large performance spaces, such as the Wang Center, showcase musical road shows and other traveling musical offerings.

Boston churches sponsor a great deal of musical activity. Many Bostonians attend Sunday morning services downtown to hear the professional choir at the venerable Church of the Advent (established in 1844) or the renowned weekly performance of the cantatas, famous choral works by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), at Emmanuel Church. The large Haitian churches in the metropolitan area, such as St. Angela’s Catholic Church in Mattapan and the First Haitian Baptist Church of Roxbury, are important sites for Haitian musical performances. Other houses of worship lend their facilities and sponsorship to musical ensembles outside the context of religious observances.

Symphony Hall, the home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, opened in 1900 and celebrated its centennial during the 2000–2001 season. Note the organ pipes mounted on the wall behind the orchestra, with the organ console on the front left-hand corner of the stage.

Boston neighborhoods provide venues for many musical events of interest to local communities. Some of the liveliest Caribbean musical events are held at settings not intended primarily for musical performance, including parks, cultural centers, and restaurants in areas such as Roxbury and Dorchester, where large Jamaican, Dominican, and Haitian populations reside. To find out the time and location of these events, one needs to speak to residents, keep an eye out for signs and posters in the area, check a community website, or call a local hotline.

The Massachusetts acoustic band Secret Sage plays on June 22, 2013, in “The Pit,” a popular performance space at the center of Harvard Square adjacent to the entrance to the “T” (Boston’s underground transit system). Along with more than 110 other musicians, Secret Sage was part of a free, live music festival mounted on fourteen different stages at the sixth annual Make Music Harvard Square Festival/Fête de la Musique. Inspired by a Paris street festival that started twenty-nine years ago, Fête de la Musique is now celebrated on the occasion of the summer solstice under many names in more than 300 cities in 108 countries worldwide.

Some soundscapes not only transform the interiors of buildings through changing sounds and rearrangement of space, but reshape the outdoors as well. For instance, Harvard Square in Cambridge is one of the liveliest settings for musical performance. There a wide variety of buskers (street musicians) who ply their trade during the hours that shops and restaurants are open. These include folksingers, accordion players, rock groups, Latin ensembles, Chinese instrumentalists, and West African musicians, most of whom also sell recordings. Various music groups from South America play in the Square. Beginning in the late 1990s, the northern Peruvian group Wayno performed outside the entrance to the Harvard Cooperative Society building (known as the “Harvard Coop”), playing traditional Peruvian melodies such as the one heard in Listening Guide 25 (see p. 94). Their music features close coordination between two players of the sikus (panpipes), aerophones consisting of multiple bamboo tubes laced together. The bomba (a large two-headed drum) is joined by a snare drum and an assortment of idiophones, including a rain stick, wind chimes, cymbal, and a rattle.

1:38 |

Date of recording: 1995 Performers: Wayno (also known as Nazca); Luis Vilcherrez, producer, composer, sikus (panpipes), guitar and vocals; Marco Coveñas musical director, composer, kenas (vertical wooden notched flute), sikus, charango (small lute), vocals, mandolina, guitar, bomba (drum) Form: Three-part (ternary) form (A B A) Tempo: Moderately quick duple Function: Entertainment |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Two panpipes, each with half of the notes of the scale, played by two different performers. In this recording, the two panpipes are recorded stereophonically, so one player can be heard from the left channel and the other from the right.

• A musical form built from two short melodic building blocks, phrases a and b, each of which varies slightly from iteration to iteration

• Various whistles, shouts, and percussion sounds in the background that enliven an otherwise repetitive song

|

STRUCTURE |

DESCRIPTION |

0:00 |

Introduction |

Five chords, played slowly and in free rhythm, comprise the introduction. Each chord has three voices: two panpipes and an aerophone (a bass flute) in a lower range. Drum rolls are heard on both the snare and the bomba. |

0:17 |

Section A Phrases a, b |

The melody is played by the panpipes, as the bomba plays on some of the strong beats. Phrase a rises to the top of the range, while phrase b, lower in the range, begins with a catchy syncopation and ends with a quick jumping figure that springs up an octave. |

0:27 |

Phrases a, b |

The two phrases are repeated. The rattle fades into the texture, sounding on every beat. |

0:38 |

Phrases b', b |

The pattern changes here. Phrase b' is the same as phrase b, except at the ending. The jumping figure of phrase b is replaced with a single note at the end of phrase b'. |

0:46 |

Phrase b', b' |

Section A ends with two more iterations of phrase b'. |

0:53 |

Section B Phrases a', b' |

Section B begins with an excerpt from phrase a. Phrase a' is the same as the second half of phrase a. A rain stick can be heard in the background just as Section B begins. |

0:59 |

Phrases a', b |

Phrase a', the excerpt from phrase a, is repeated. Phrase b is played in its entirety, including the jumping figure, as a transition to the next section. Cymbal and wind chime are heard in the background. |

1:06 |

Section A Phrases a, b |

Section A returns. From here until the end of the recording, the melody is identical to Section A above. The snare drum now creeps into the texture. |

1:17 |

Phrases a, b |

|

1:27 |

Phrases b', b |

The cries and birdcalls grow in intensity. |

1:35 |

Phrase b' |

|

1:38 |

Recording ends. |

Girls from the Hellenic American School in Lowell, Massachusetts, perform a traditional dance at Boston City Hall Plaza in celebration of Greek Independence Day (Greece won its independence from the Ottoman empire in 1821). Eighty-five thousand people attended the parade, including the mayors of Athens and several other Greek cities.

First Night features so many simultaneous events that participants must keep the multipage program close at hand.

Many musical events take place at Boston’s Government Center, a complex that includes Boston City Hall. Government Center was previously known as Scollay Square, the site of the famous Lighthouse Pub patronized by President John F. Kennedy during his student days, as well as other landmarks mentioned in The M.T.A. Song discussed later. The large concrete plaza in front of City Hall was intended to be spacious enough to accommodate many kinds of musical celebrations.

The massive, bi-level brick and stone atrium inside City Hall can also be transformed on special occasions by festive decorations and musical performances. Music often marks the beginning and end of civic ceremonial gatherings there.

Even the stately old Boston Common and Public Garden are transformed through musical performance on special occasions, such as the annual “First Night” celebration held every New Year’s Eve in Boston since the early 1980s. Boston hosted the original First Night celebration in the United States, featuring performances and exhibitions by over one thousand musical groups and artists. Throughout the day and evening, the open Common and the surrounding area are transformed into a variety of performance spaces.

Musical performances at special times in a variety of urban settings reinforce the connections among the diverse populations living within a particular area as well as incorporate them into the broader rhythm of city life. By looking closely at the side-by-side performance of so many music traditions and the transformation of large areas for these musical events, we can better understand the common practice of reimagining local spaces as larger settings for performance.

WHO MAKES THE MUSIC?

The Boston soundscape arises from a complex array of music cultures. In Boston, like most of multiethnic North America, where almost every city or town has some measure of cultural diversity, ties of descent or a shared cultural heritage generate a great deal of musical activity. Boston is home to many ethnic communities, each contributing to the greater urban soundscape. Some ethnic groups, such as the British, Irish, Italians, Haitians, and Cape Verdeans, arrived in New England early, and, swelled by later waves of immigration, have helped build the city into its present form. Others, including many African, Caribbean, and Russian immigrants, have come more recently. Here we will focus on several long-established ethnic groups—the Irish and Portuguese, along with other Portuguese-speaking communities such as Brazilians and Cape Verdeans.

IRISH Irish immigrants began to arrive in New England during the eighteenth century; their numbers increased in the mid-nineteenth century because of hardships in Ireland, particularly the great potato famine of the late 1840s. It is estimated that four million Irish arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1900. Musical life in Boston reflects the Irish presence through traditional Irish fiddling in pubs and the sound of bagpipes at many civic and cultural events.

Annual activities such as the Boston College’s Gaelic Roots summer festival, discontinued in 2003, helped make Boston the “Irish capital of the United States.” Home to one of the great concentrations of people of Irish descent, Boston houses important centers for Irish American history, genealogy, and culture at the Boston Public Library and the Burns Library of Boston College.

This sign in Gaelic (“Welcome to South Boston”) was painted on a Dorchester Avenue building in South Boston. Note the strong references to Ireland, with the four coats of arms from the major regions of the country. The Celtic cross at the center of the sign can be interpreted as an emblem of Irish identity and, given the reference to two major Irish political organizations that sought to end British control of the country (Sinn Fein and Noraid), as a political symbol. The sign has since been painted over.

Not surprisingly, Boston and its Irish inhabitants have been the subject of songs composed and transmitted within the community. Narrative songs, known as ballads, commemorate important events and memorable individuals. Many Irish ballads are political in their subject matter, providing a focal point for patriotic sentiments on important anniversaries of Irish history and celebrating the longtime Irish resistance to English rule.

The Ballad of Buddy McClean (see Listening Guide 26) commemorates composer John Hurley’s fellow longshoreman, Buddy McClean, who was murdered after he resisted an effort by organized crime to take over the Boston dockworkers’ unions in the 1950s and 1960s. The text of the song, especially in verses 2 and 3, connects the fight for workers’ rights in Boston with the fight for independence in Ireland.

The melody is simple and repetitive, which helps both the singer and listeners to remember the ballad, and the guitar accompaniment uses a total of four chords, all fairly easy even for a beginning guitarist to play. These factors enhance the ballad’s potential to record and transmit history and thereby to construct and reinforce a sense of identity among Irish Americans, especially those from Boston.

PORTUGUESE The Portuguese were among the earliest settlers in New England, and a steady stream of immigrants settled in Boston and Cambridge since the mid-twentieth century. These expatriate Portuguese communities came mainly from Portugal itself, as well as from the nearby Portuguese territories of the Cape Verde (now Cabo Verde) Islands and the Azores. In recent years, large numbers of Brazilians have swelled the number of Portuguese-speaking Bostonians; for instance, between 2000 and 2003, one out of every five new arrivals to Massachusetts was Brazilian, the most of any single immigrant community.22

3:01 |

Composer: John Hurley Date of recording: 1998 Performers: Derek Warfield, voice and mandolin; Joe O’Rourke, guitar and chorus; Des Sheerin, string bass; Joe Finn, uilleann pipes; Loe Finn, pennywhistle; Kefin Sheerin, accordion; Joe Cooney, banjo; Athena Terais, fiddle; Pearse Warfield, bodhrán (frame drum) and chorus; Peter Wrafter, chorus Form: Strophic ballad with refrain Tempo: Moderate tempo, triple meter Function: Commemoration of local hero |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Vocal style and instruments (guitar, banjo, accordion) typical of American folk music, along with Irish fiddle, frame drum, bagpipes, and pennywhistle, a small flute made of wood or plastic

• Traditional strophic ballad form, with alternation of verse and refrain

|

STRUCTURE AND TEXT |

DESCRIPTION |

|

0:00 |

Verse I’ll sing you a song of the deeds that were done, Of the struggles of conflict and tears, Of the men on the run who fought against guns, That brought the community fear.

Sought fame or great power or acclaim. You had no wealth or might, but you knew wrong from right, And your fight for justice was clear. |

Each verse consists of two four-line stanzas. The melody begins on the tonic (central pitch), with several short ascending phrases, each followed by a drop. The first stanza of each verse ends inconclusively at the lowest point. Stanza 2 is higher, livelier, and ends conclusively on the central pitch (tonic). |

|

0:38 |

Refrain Sing away, hills of Boston, With the spirit of Buddy McClean! The longshoreman’s teamsters are talking Of their hero now, Buddy McClean.

Than to lay down his life for his friends? Winter Hill tells the tale of the strong Irish gale Who was loyal was pure and was true. |

The refrain likewise contains two stanzas. Additional singers are heard on the refrain, and a countermelody (played first by the flute and then by the fiddle) becomes prominent. The second stanza of the refrain uses the same melody and harmonies as does the second stanza of the verse. |

|

1:12 |

Verse Those mobsters of crime said the good would be dying If you did not submit to their ways. That the fit would be lame if you’d not play their game, And your friends would know more happy days. |

The second verse begins. |

|

Men of liberty, freedom, and courage Believed that your stand it was true. And the unions you saved for the homes of the brave And were joined by the faithful and few. |

|

|

1:46 |

Refrain |

|

|

2:21 |

Verse The Irish McCleans would kneel to no Queen. They were proud of the old sod of green. You were Buddy to all, and you answered the call, On the waterfront you were the king.

For your wife and your family and home. And you bowed to no one whether gangster or gun, And worked for the American dream. |

Third verse. |

|

2:55 |

Refrain |

|

|

3:00 |

|

Fade-out. |

A musical form popular among many Bostonians of Portuguese descent is the fado (pronounced “FAH-doe”), a song closely associated with Lisbon, the Portuguese capital. Fado, which means “fate,” gives voice to nostalgia for the country left behind. In its expression of longing for a homeland, the fado became a powerful symbol for both Portuguese immigrants and those of Portuguese descent living abroad. Fado is sometimes compared to the blues because of its heartfelt expression of loss and despair. Said to have originated among Portuguese sailors who spent long periods of time away from home, the fado in Lisbon and urban centers abroad is usually performed in clubs and restaurants. The fado became less popular after the 1974 Portuguese revolution because of its association with the authoritarian regime of dictator Antonio Salazar, but it slowly recovered its status as a symbol of Portugal in the 1980s and 1990s.

Portuguese singer Amália Rodrigues had an international following. Here she performs at Olympia Hall in Paris, one of the most famous music halls in the world, on April 21, 1987.

Today Portuguese Americans hear the fado largely through recordings imported from Portugal, although a new generation of young Portuguese fado singers such as Misia and Mariza tour internationally and perform often in the Boston area. But fado aficionados constantly compare the young singers to Amália Rodrigues, who before her death in 1999 was the foremost interpreter of the fado in twentieth-century Portugal. Thousands of Portuguese poured into the streets of Lisbon for her funeral, and political candidates, out of respect, halted their campaigning until the funeral services were over.23 Born around 1920, Rodrigues made her first recording in 1945, released more than 170 albums and became an international film star over the years.

Today Rodrigues remains a muse and inspiration to young fado singers: “Everywhere I go, everybody knows what fado is thanks to Amália,” the singer Misia has said. “She had that wonderful voice, she inspired many new fados, and she wrote beautiful lyrics herself.” 24 Some say that the singer Mariza sounds “like the young Amália, with soul.” Rodrigues is thought to have personified the fado, wearing black clothes of mourning during her performances and once saying that “I have so much sadness in me, I am a pessimist, a nihilist, everything fado demands in a singer, I have in me.”25

In Listening Guide 27 (see p. 100), Amália Rodrigues sings a classic fado song, Fado Lisboeta, which is known for its sophisticated poetry and complex harmony. Rodrigues conveys saudade (a feeling of longing or yearning) through her tone color. She also expresses emotion by subtly slowing the tempo of the song near the end of phrases.

CAPE VERDEANS Not all members of the Portuguese-speaking community of Boston come from mainland Portugal. Many are from Cape Verde, a dry, tropical archipelago of ten islands located about 300 miles off the coast of West Africa.26 Home to the first permanent European settlement and a site where West Africans were forcibly brought, Cape Verde served as a way station between Africa, Europe, and the Americas. During five centuries under Portuguese colonial rule until the country achieved independence in 1975, Cape Verde suffered repeated droughts, famine, and economic decline. As a result, beginning in the 1800s, many Cape Verdean men joined the crews of Atlantic whaling vessels that passed the islands, traveling to the United States in search of economic opportunity. Cape Verdeans were the first free people of African descent to travel to the United States voluntarily during the time of slavery. As the whaling industry declined, Cape Verdeans purchased their own ships and became the first immigrant group to control their own means of transportation from their historical homeland to the United States. Early Cape Verdean immigrants settled in southeastern New England, where many served as laborers at Cape Cod cranberry bogs, as longshoremen on the New England waterfront, and as domestic workers.

Although Cape Verdeans held Portuguese passports until 1975, they were treated as second-class citizens by many mainland Portuguese because of their African origin. Their distinctive cultural background and especially their language, Cape Verdean Creole, led them to maintain a distance from the African American community. Generally viewed as black within the American biracial system, they established their own communities, where they celebrated their distinctive cultural background through food, music, and dance.

Senior citizens from the Cape Verdean community perform traditional songs and dances as part of the ensemble Pilon Cola, named after the cola (literally, “tail”) dance that is performed around a pilon, the large wooden pestle shown here, which is used as both a corn grinder and drum.

Cape Verde’s music is perhaps its richest export. Indigenous Cape Verdean styles combine with influences from the Portuguese fado, as well as with global genres such as samba, zouk, and hip hop. Though Cape Verde did not have its first recording studio until the late 1990s, the mobility of Cape Verdeans living in New England, Portugal, the Netherlands, and France, as well as circulation of recordings, made collaborations with musicians at home in Cape Verde possible. A joke told in the community says that “one in four Cape Verdeans will release a CD in his or her lifetime.”

2:55 |

Date of recording: 1960s, rereleased in 1992 Composers: C. Dias and A. Do Vale Performers: Amália Rodrigues, voice; Jaime Santos, guitar; Domingo Camarinha, guitar Form: Fado canção, a strophic form with refrain Tempo: Moderate quadruple meter Function: Entertainment, personal reflection |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The ways in which the strophic fado text, with alternation of verse and refrain, provides a personal, emotional statement, while simultaneously evoking a nocturnal setting in Lisbon

• Famous fadista Amália Rodrigues’s expressive vocal style conveying saudade (longing or yearning)

• Twelve-stringed Portuguese guitars (guitarras) that are finger-picked to achieve a soft timbre; guitarists pluck the individual pitches of a chord (called an arpeggio) rather than strum the entire chord at one time

• A subtle interaction between the guitarists and the singer, allowing for expressive changes in tempo known as rubato, especially near the end of phrases

|

STRUCTURE AND TEXT |

TRANSLATION |

DESCRIPTION |

0:00 |

Instrumental introduction |

|

The guitars establish a syncopated rhythm. The introduction begins in the major mode and ends in minor. |

0:10 |

Verse 1 |

||

|

Phrase a |

||

|

Não queiram mal a quem canta quando uma garganta em ar se desgarra, |

Don’t hold it against one who sings when a voice wells up in challenge, |

A rapid syllabic text-setting, with three notes (and therefore three syllables) per beat. |

|

Phrase b |

||

|

porque [y] a mágos já não é tanta se é confissada a uma guitarra. |

because his pain is not so great when confessed to a guitar. |

A complementary (“consequent”) phrase responds to the first (“antecedent”) phrase. |

|

Phrase a' |

||

|

Quem canta sempre se ausenta na hora cinzenta de sua amargura, |

He who sings always retreats in the ashen hours of his suffering, |

The first phrase is repeated with different words. |

|

Phrase c |

||

|

não sente a cruz tão pesada na longa rua [strada] de desventura. |

and the cross he bears doesn’t feel so heavy on the long road of misfortune. |

This time, a different phrase responds, ending on the tonic. The singer makes dramatic use of rubato (flexible, expressive tempo changes) and the guitars emphasize the transition to the refrain. |

0:39 |

Refrain |

||

|

Phrases d–e |

||

|

Eu só entendo o fado plangente amargurado |

I only feel fado, plaintive and sorrowful |

The guitar melody traces “broken chords,” in which individual pitches are plucked separately, called arpeggios. This section begins in the major mode. As in the verse, the phrases in the refrain respond to each other, acting as antecedent and consequent phrases. |

|

na noite a soluçar baixinho, |

while I sob quietly in the night. |

|

|

Phrases f–g |

||

|

que chega a meu coração tão magoado, |

It touches my heart, so pained |

|

|

tão frio como as neves do caminho, |

and as cold as the snow on the road, |

|

|

Phrases d'–e' |

||

|

que chora uma saudade ou canta ansiedade |

that weeps with longing or sings the yearning |

The melody at the beginning of the refrain is repeated with different words. |

|

de quem tem por amor chorado. |

of one who has wept for love. |

|

|

Phrases h–i |

||

|

Dirão que isto é fatal, é natural, mas é [o] lisboeta, isto é o que é o fado. |

They’ll say that this is fateful, that it’s only natural, but this is Lisbon, this is fado. |

With the mention of fado, the song switches back into the minor mode. |

1:30 |

Verse 2 |

||

|

Phrase a |

||

|

Oiço guitarras vibrando vozes cantando na rua sombria, |

I hear the strumming of guitars and voices singing in the gloomy streets, |

The second verse has the same musical structure as the first, but with different words. |

|

Phrase b |

||

|

que as luzes vão se apagando a anunciar que já é dia. |

as the lights go out announcing the break of day. |

|

|

Phrase a' |

||

|

Fecho em silêncio a janela, |

Silently, I close the window, |

|

|

se ouve na viela rumores de ternura, |

sounds of tenderness may be heard in the alleyway, |

|

|

Phrase c |

||

|

surge a manhã fresca e calma, |

the morning unfolds fresh and tranquil, |

|

|

só em minh’alma é noite escura. |

only in my soul is it darkest night. |

|

2:01 |

Refrain |

|

The refrain repeats, this time ending in the major mode at 2:55. |

In New England, many Americans of Cape Verdean descent have become prominent musicians, including Maria de Barros, the goddaughter of the famous Cape Verdean singer Cesária Évora, who died in 2011. De Barros was born in Senegal and raised in Mauritania until her family settled in Rhode Island during her high school years. She began singing and performing full-time after moving to Los Angeles, where she still resides. Influenced by Cape Verdean music as well as Latin American and Caribbean styles, especially reggae, de Barros is known as the “queen of the coladeira,” a fast-paced Cape Verdean dance genre. When visiting the New England area, de Barros often performs at Restaurante Cesária in Dorchester, Zeiterion Theatre in New Bedford, Rosinha’s Restaurant in Pawtucket, and at the Lowell Folk Festival and at the many Cape Verdean music festivals held each summer.

In her song, Riberonzinha, heard in Listening Guide 28, Maria and her band call out to their ancestors and relatives in rural Cape Verde, describing the agricultural lifestyle and constant worry over drought. The reference to “Tintina Dilintin Cripin,” a name made up by the songwriters, draws on an old Cape Verdean tale about a witch’s power over visitors to her house. It is said that after a visitor drinks from a glass, the witch flips the glass upside down and the person cannot leave until the glass is put right-side up. Songs such as these, when performed by and for Cape Verdean Americans, help to express and perhaps mitigate the intense sodade (nostalgia or longing, similar to the Portuguese saudade) that many feel for the life and customs left behind. The song also reinforces the strong social and economic ties between the diaspora and the homeland. The rhythm of the song is the classical cavaquinho pattern of coladeira, but it is identical to a common rhythm of reggae music. Maria de Barros says that “this song was born out of a mix of traditional rhythms of two different words: Jamaica and Cape Verde. Listen to it and let it transport you.” 27

Today, it is widely believed that more Cape Verdeans live abroad than in Cape Verde itself, although census numbers are difficult to come by. However, there is no question that the largest concentration of people of Cape Verdean descent outside of Cape Verde live on the New England coast, stretching from Boston to Providence, Rhode Island.

Maria de Barros performs at an international festival in Puebla, Mexico, with her band, including (left to right) Kalu Monteiro, drums; Fabio Soares, guitar; Zerui Depina, cavaquinho; Sandro Rebel, keyboards; and Djim Job, bass.

While both old and new ethnic communities enrich musical life in Boston, many other residents contribute to the soundscape as well. Boston is a magnet for people attracted by opportunities in business and education, many of whom reside in the metropolitan area on a short-term basis. Many people support music cultures that they have encounter by chance and to which they are attracted by virtue of the music’s sound or setting.

Many music traditions today are perpetuated by affinity communities, groups of people who come together to participate in particular forms of musicmaking. A good example is the folk dance groups that have spread throughout the Boston area in the last forty years, bringing people of diverse backgrounds together through dance. We will see next that affinity communities generate some of the most distinctive features of the Boston soundscape.

2:40 |

Date: 2003 Composers: Kalú Monteiro and Djim Job Performers: Maria de Barros and ensemble Form: Coladeira, modified strophic form with verses and refrain Tempo: Moderate quadruple meter, slower than usual coladeira, similar to reggae rhythm Function: Local song for social gatherings, celebrations, and dance |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The relationship between the cavaquinho (the high-pitched strummed and plucked chordophone) accenting beats 1 and 3, with guitar and percussion emphasizing beats 2 and 4

• The repeating melodic elements within each verse enlivened by the interplay of the female voice with male chorus

|

STRUCTURE AND TEXT |

TRANSLATION |

DESCRIPTION |

0:00 |

Refrain |

||

0:12 |

We le le le le We le le le le le la We le le le le Riberonzinha (repeated) |

Vocables and name of mountain |

Male chorus enters on vocables, accompanied by solo cavaquinho, which emphasizes beats 1 and 3, while guitars accent beats 2 and 4. Various percussion sounds interject accents. Each vocal phrase extends four beats followed by a four-beat instrumental phrase. Four-phrase guitar interlude played between repetition of verse. |

0:44 |

Melody A (one verse) |

||

|

La t’cima na Riberonzinha Tem midje ferel inganha Trepitche pa mui cana Matanca d’porco e lenha na lume (repeated) |

Atop Riberonzinha There’s corn on the cob People grinding sugar cane Pork roasting on an open fire |

De Barros enters, accompanied by cavaquinho, guitars, and percussion, with brief melodic punctuation at end of verse by xylophone (1:00) and, on repetition, by harmonica (1:15). |

1:18 |

Melody A (one verse) |

||

|

Tintina dilintin cripin Fi, d’santoma di nha rabona Fetcera di roba ezede Eje imborcal caneca pa f’ca marode (repeated) |

Tintina dilintin cripin Daughter of Santoma di Nha Rabona The sour-tailed witch They tipped over the can to trap her |

Male chorus responds “tin” to the first phrase in addition to instrumental transitions by guitar and, subsequently, harmonica. |

1:49 |

Melody B and B1 (two verses) |

||

|

Jonzin ba cutchi quel midje Ranja ferel p’kel c’mida d’tchuque Antonina frita tchuricec Guiza catchupa pa mata injum |

Jonzin, grind the corn Get the leftover wheat to feed the pigs Antonina, fry the sausage Reheat the catchupa so we can eat |

Contrasting melody (B) enters, repeated for both new verses of text. |

2:03 |

Joel na tchom v’roide oi pa ceu Ta roga pa seraçon Nhor Deus no ceu se mandone tchuva Pa tude criston na riberonzinha |

On our knees, looking up at the sky Praying for rain clouds God in the heavens please send us rain For all the folks in Riberonzinha |

|

2:17 |

Refrain |

||

|

We le le le le We le le le le le la We le le le le Riberonzinha (verse repeated) |

Vocables and name of mountain |

Male chorus reenters, with added instrumental, especially percussion, and improvisation. |

2:36 |

|

Fade-out. |

|

BOSTON’S DEFINING MUSICAL COMMUNITIES

Distinctive characteristics of Boston, notably the city’s history, location, and diverse population, have given rise to three important soundscapes within the broader context of city musical life: campus music, folk music, and early music. All three of these soundscapes have roots in Euro-American history, but each has been transformed by cross-cultural musical connections. Individuals from a variety of backgrounds who today constitute cohesive affinity communities transmit these three soundscapes; many of these participants cross back and forth between two or more of these soundscapes, linking one to the other. Because of their size, internal complexity, and mutual interaction, Boston’s campus music, folk music, and early music soundscapes help define Boston’s musical profile.

CAMPUS MUSIC Boston nurtures a rich array of music traditions at the world-renowned institutions of higher education in the metropolitan area. The history of greater Boston can to a certain extent be told through the history of its colleges, universities, and conservatories, starting with the founding in 1636 of the divinity school that shortly thereafter became Harvard University, the establishment of Boston University in 1839, the founding of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1861, and the launching of the nation’s oldest music conservatory, the New England Conservatory, in 1867. Numerous other institutions with active traditions of musicmaking are located throughout the Boston metropolitan area.

This flyer for a Taiwanese Cultural Society meeting at the Harvard University student center blends old Boston images with Taiwanese customs and music.

Many of Boston’s oldest musical institutions had their roots in campus musical life, and the musical interaction between town and gown was—and remains—close. One notable example is the impact that jazz musicians from the Berklee College of Music have had on Boston club life. Boston clubs such as Wally’s Cafe have for more than half a century provided a setting where young jazz students could hone their talents.

Virtually every Boston-area campus is a small city with its own distinctive soundscapes, sustaining a dazzling array of musical activities, ensembles, and music events. Partly because of the increasingly international and multiethnic nature of student populations at these institutions, diverse musical styles have proliferated in recent years. These styles have contributed to the student orchestras, choirs, and close-harmony singing groups established in the earliest days of many campuses.

Although campus musical life in the past drew mainly on historical Western music ensembles, the later twentieth century has seen the proliferation of groups featuring a range of avant-garde, popular, and international musics. There is little doubt that the broader Boston soundscape has been greatly enriched by the wide array of music traditions easily accessible on area campuses. West African drumming is taught at Tufts University; at Harvard, Gumboot dancers perform and teach the dances of South African miners, and another group teaches Korean drumming and dance; MIT features the study and performance of North Indian and Senegalese music. Widely represented on nearly all campuses are student dance groups, including South Asian, Israeli, Mexican, Chinese, Eastern European, Latin, jazz, funk, and hip hop dancers.

Among the international music ensembles most prominent on college campuses in Boston and across North America and the world are Indonesian instrumental groups known as gamelan. While there are several important Indonesian gamelan traditions, two have been widely studied and are today established worldwide. One of these arose first on the island of Java early in the Common Era, and the second later in Bali. Javanese and Balinese gamelan are closely related but are distinguished from each other by different instruments, tunings, and playing techniques. Both Balinese and Javanese gamelan are active in the Boston metropolitan area on the MIT and Tufts campuses, drawing players from the student population as well as from the community at large. Here we will focus on the Balinese gamelan and discuss how this venerable Southeast Asian music tradition has become part of the Boston soundscape (see “Sound Sources: The Balinese Gamelan,” p. 106).

The popularity of gamelan music in Boston and on college campuses around the world is a phenomenon with its roots in the nineteenth-century colonial era. However, we can trace the history of the Balinese gamelan back to the early sixteenth century, when members of the Javanese court and its musicians fled to Bali. Over the next several centuries, the gamelan spread to Hindu temples and to villages across that island. Used in a variety of religious and secular ceremonies, as well as in musical theater, the gamelan became a ubiquitous presence in Balinese life. In recent decades, the gamelan has assumed an increasingly important role in the Balinese tourist industry as well.

SOUND SOURCES |

|

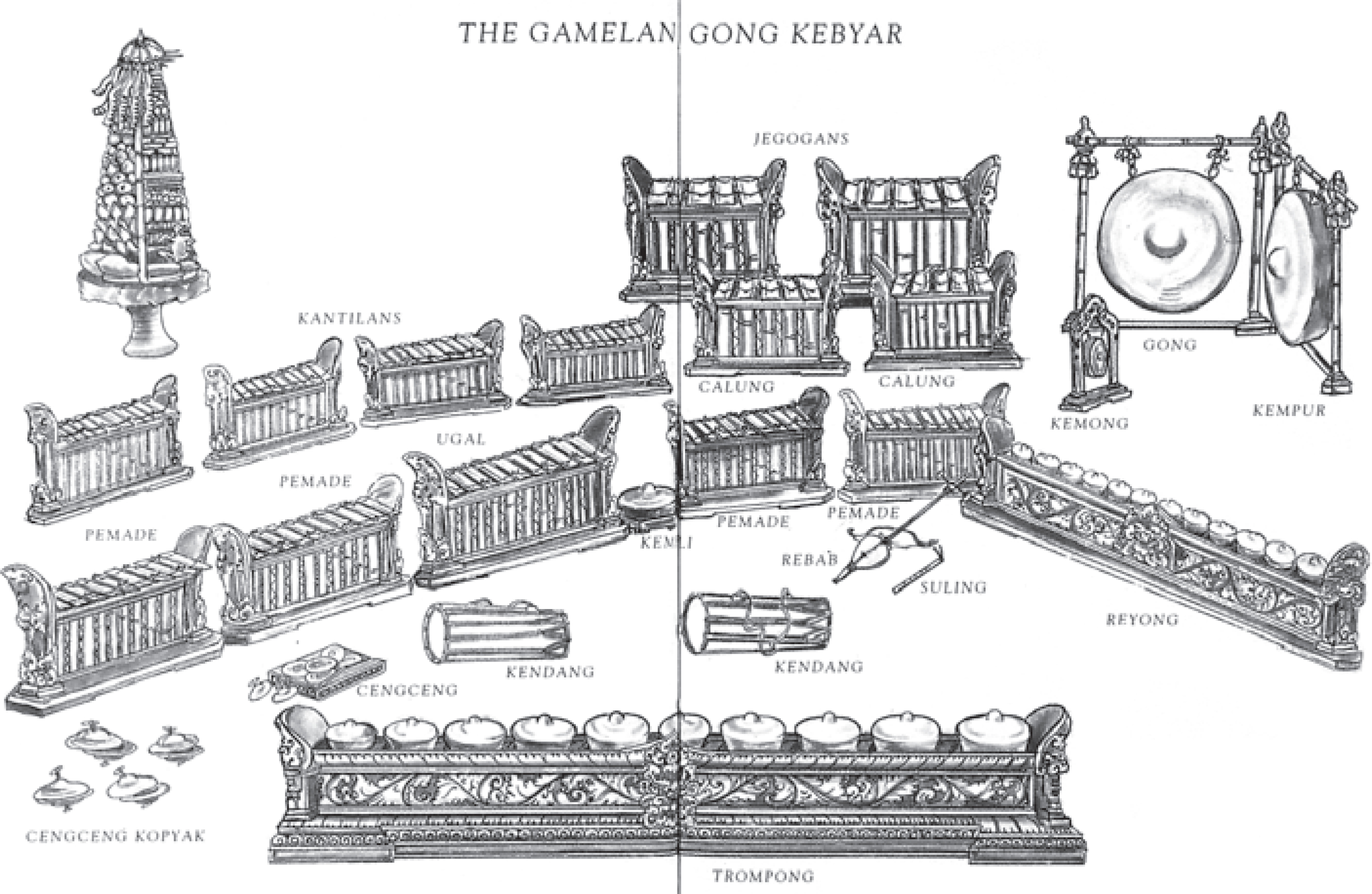

THE BALINESE GAMELAN

Although the Balinese gamelan consists of instruments made of wood and bamboo—including one or two drums, flutes, and a bowed lute called a rebab (“reh-BAHB”)—gongs and instruments of the xylophone type made of bronze dominate the ensemble’s distinctive sound. Here we will focus on the Balinese gamelan, with particular attention to the gamelan gong kebyar, the most important gamelan in twentieth-century Bali.

The metal idiophones (sometimes called metallophones) of the Balinese gamelan are divided between keyed and gong instruments struck with different types of mallets. The keyed instruments include the gangsa (“GHAHNG-sah”) family, each with ten bronze keys suspended on cords hanging over bamboo resonators within a wooden case. In general, the bigger the instrument, the lower the pitch.

The gangsa family of instruments expand on and ornament the main melody. The highest-pitched gangsa are the four small kantilan (“kahn-TEE-lahn”); tuned an octave below them are the four somewhat larger gangsa pemade (“puh-MAH-deh”); and another octave lower, one or two tall gangsa called ugal (“OO-gahl”). The ugal usually plays a different musical part from the kantilan and pemade, and for this reason musicians sometimes talk about the “gangsa parts” and the “ugal part” separately, even though the ugal is technically a gangsa.

Several other metallophones with five keys support the gangsa and ugal parts, and play at a slower rate of speed the core tones that constitute the basic gamelan melody. These large instruments include two calung (“chah-LOONG”) which overlap in range with the ugal, and the jegogan (“djuh-GOE-gone”) which is even larger and is tuned one octave lower than the calung. The hammer used for the calung and jegogan is padded and softer than those used for the gangsas and ugal, producing a more delicate sound.

The gongs of the gamelan are made of bronze and have a raised boss in the middle on which they are struck with mallets. Different gongs serve colotomic (time-keeping) and melodic functions; the hanging gongs keep the time while most gongs on racks have melodic functions. The number of gongs varies according to the particular gamelan, but most use one or two large, hanging gongs (gong ageng) to mark the beginnings and endings of melodies. The smaller hanging kempur (“kehm-POOR”) marks other divisions in the time cycle, as does the kemong (also called klentong). The kempli (“kehm-PLEE”), a single small gong in a wooden frame, keeps a regular, crisp beat that provides a point of reference for all the musicians of the gamelan.

Gongs with prominent melodic roles include sets of eight to fourteen pot gongs in frames. This instrument is called a trompong when it is played by a soloist, and is termed a reyong (“RAY-yong”) when played by four people, each attending to a few gongs. The reyong is particularly famous for elaborate ornamentation and loud chords. The final metallophone is the ceng-ceng (“CHENG-cheng”), which are noisy cymbals, usually set on a wooden base.

A pair of double-headed, cylindrical membranophones called kendang lead the gamelan. The higher pitched kendang of the pair is called the male drum, while the lower pitched is the female, despite their reversal of the range of male and female voices. The lower female drum usually sets the pace and signals upcoming changes to the other musicians.

Bamboo flutes (suling, pronounced “SOO-ling”), played with the circular breathing technique, provide another melodic line, as does the tone of the rebab, a two-stringed bowed lute that can be heard mainly in quieter passages.28

The instruments of the Balinese gamelan can be heard in the performance of the dance Taruna Jaya, Listening Guide 29 (see p. 110).

Stamford Raffles, a colonial governor in Java, brought the first Javanese gamelan ensemble outside Southeast Asia to England in 1816. The appearance of a Javanese gamelan at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris attracted the interest of French composer Claude Debussy and others, as did the performance of a Balinese gamelan at the subsequent 1900 Exposition. The Dutch colonial presence in Indonesia also attracted Western scholars to the country, where they worked closely with Indonesian musicians and scholars. During a concert tour of Java in 1919, a Dutch musician named Jaap Kunst became intrigued with the gamelan and subsequently returned as a colonial official to live in Java and carry out research on the gamelan through the mid-1930s.

Artist’s sketch of Gamelan Gong Kebyar.

Kunst’s subsequent career as a scholar of Javanese gamelan music after his return to Amsterdam inspired others, in particular his student Ki Mantle Hood, an American who later established the first ethnomusicology program in the United States at UCLA. In 1958, Hood purchased for UCLA the Javanese gamelan Venerable Dark Cloud, which remains at that institution today. The second half of the twentieth century saw an explosion of scholars studying Javanese, Balinese, and Sundanese gamelan music and the proliferation of gamelan ensembles worldwide, including all over Europe—40 sets in Britain, 150 in North America, and others in East Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Latin America, and even Africa.29

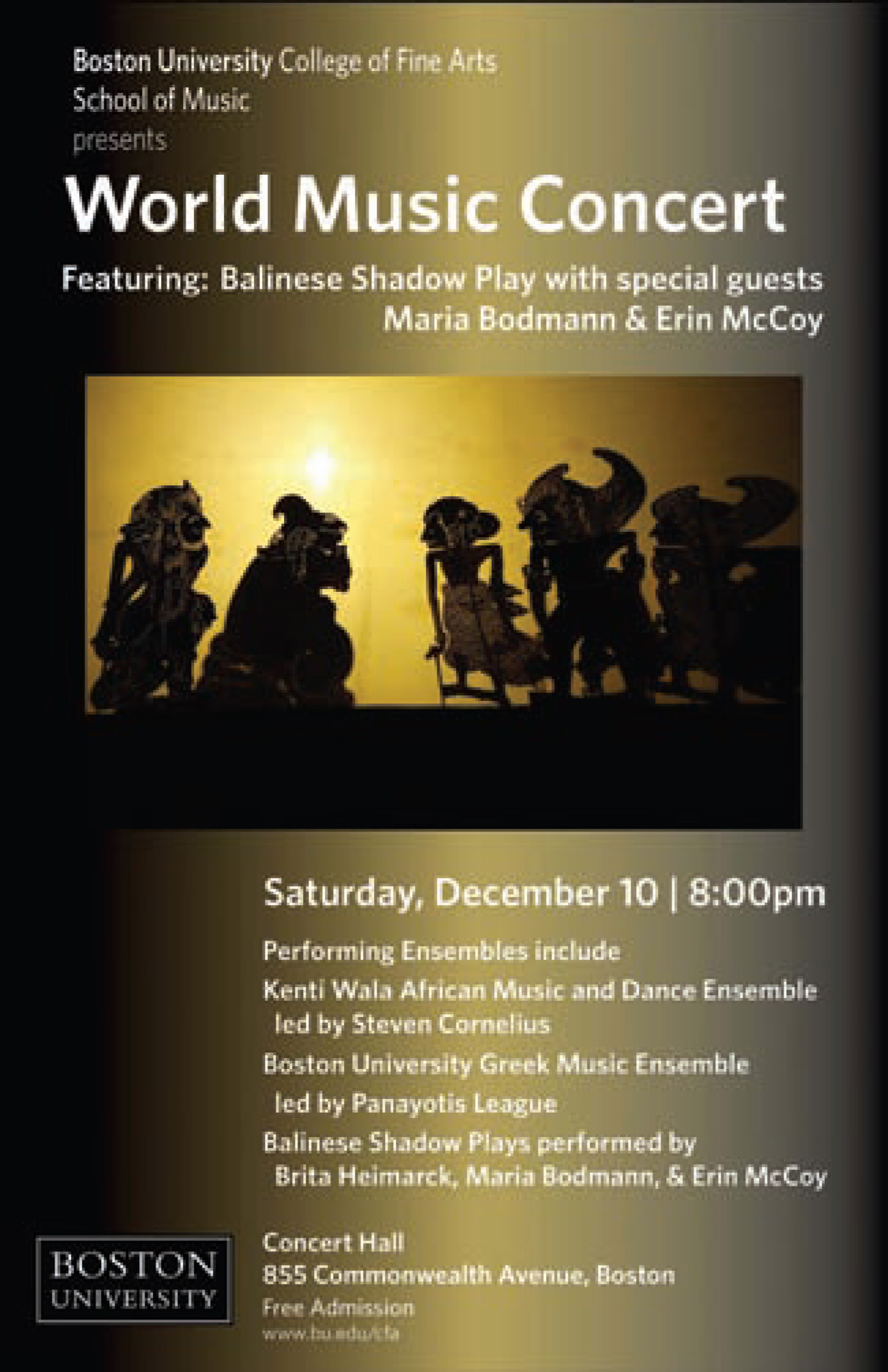

The School of Music at Boston University College of Fine Arts presents an array of world music in performance, including this concert featuring a Balinese shadow play, a West African Music and Dance ensemble, and a Greek music group.

Gamelan were imported from Bali and Java to a number of other campuses, including Wesleyan University, the University of Michigan, the University of California, Berkeley, and the Eastman School of Music, to name only a few. As a result, generations of students and community members have played these instruments and become aficionados of Indonesian music. In most cases, accomplished Balinese and Javanese musicians have collaborated with local faculty, arriving for visits or permanent positions to teach gamelan on college campuses. Many Indonesian musicians, dancers, and scholars have established international careers between the United States and Indonesia, including Hardja Susilo (UCLA), Sumarsam (Wesleyan University), Desak Made Suarti Laksi and I Nyoman Catra (College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA), Undang Sumarna (University of California, Santa Cruz), and others.

Members of Gamelan Galak Tika rehearse during a trip to Bali in summer, 2005, led by Evan Ziporyn (foreground), who is playing the kendang.

The gamelan became a symbol of Indonesian culture and national identity during the second half of the twentieth century, and the Indonesian government actively supported the spread of gamelan ensembles abroad, establishing performing groups in residence at their embassies and consulates.30 In the past, gamelan have also been presented as official gifts to foreign governments, sometimes remaining in unexpected places, such as the Javanese gamelan given to Ethiopia’s emperor Haile Selassie, still preserved at the Institute for Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. The active global life of the gamelan has also influenced transmission of gamelan music at home in Bali, where one can learn to play through traditional apprenticeships with master musicians or through instruction in Balinese music conservatories.

Historical and political factors have helped shape the international spread of the gamelan, but there is no doubt that the sound of the music has been the central attraction. Composers worldwide since Debussy have been drawn to the gamelan’s sound, many inspired by the experience of Colin McPhee, a Canadian composer who heard the first recordings of Balinese gamelan music made in the 1920s and who later lived in Bali in the years before World War II. McPhee wrote books about the gamelan and his experience in Bali and based some of his compositions for Western instruments on the Balinese gamelan’s sound and textures. Others have followed in McPhee’s footsteps, including Michael Tenzer, a leading scholar of Balinese gamelan music who established ensembles at Yale and the University of British Columbia, and composer/performer Evan Ziporyn, founder of Gamelan Galak Tika at MIT.

Balinese gamelan music is organized according to rhythmic cycles, with the large gong sounding at a point that is simultaneously the end of one cycle and the beginning of the next. It has been suggested that this cyclic way of organizing musical time reflects the Hindu belief in reincarnation and natural harvest cycles. Some instruments mark various parts of the rhythmic cycle, while others play a core melody or variations on it.31 The complex, many-voiced texture that results from these layers of different rhythms and melodies is, as we have noted in Chapter 1, called “polyphony.”

Gamelan expert and composer Evan Ziporyn based his opera, A House of Bali, on a book of the same title by composer Colin McPhee about McPhee’s years living in Bali. The opera premiered in Bali in 2009 and had its American premiere in Berkeley, California, a few months later. Sound clips and photographs as well as many interviews and articles about the production can be accessed on the Internet.

Balinese gamelan music does not have a universal standard of pitch. However, the instruments of a gamelan are tuned to each other, lending each ensemble a distinctive sound quality; the exact pitches vary slightly from one gamelan to the next. One of the most interesting and distinctive aspects of the Balinese gamelan is the use of the acoustical phenomenon called beating tones, a type of shimmering sound that occurs when the same music is played on a pair of similar instruments that are deliberately tuned at slightly different frequencies.

New compositions and innovative combinations of Balinese and Western instruments are part of gamelan practice in both Bali and around the globe, but most gamelan, such as Gamelan Galak Tika in Boston, continue to perform traditional pieces from the gamelan repertory as well as mount programs including theatrical elements and dance. We will take a closer look at gamelan innovations and Balinese/American collaboration in Chapter 6. Listening Guide 29 (see p. 110) is a lengthy excerpt of a well-known Balinese dance piece, Taruna Jaya. The sudden breaks (angsel) and strong rhythms so characteristic of the gamelan gong kebyar style are reinforced by the dancers as they suddenly assume new poses or change directions.32 Balinese gamelan are also known for their facility in playing interlocking parts, termed kotekan. After you have listened to Taruna Jaya in Listening Guide 29, try to master this technique (see “Try It Out: Experience Kotekan,” p. 112).

Beyond their broadly international musical styles, represented by ensembles such as gamelan, Boston campuses have folk music clubs as well as organizations that present performances of a wide array of early music.

FOLK MUSIC The term “folk music” is a complicated one that merits a brief discussion since it encompasses two related but distinct phenomena. The expression “folk music” has been used by scholars since the eighteenth century to refer to music transmitted through oral tradition by nonprofessional musicians. During the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in many locales, these orally transmitted folk music traditions were collected and notated by folklorists and early ethnomusicologists. Older songs also began to be revived and performed by professionals and groups in settings including cultural organizations, schools and universities, and ensembles organized to represent entire nations.

The folk music soundscape features a variety of world music traditions, including regular performances by individuals such as Arab artist Karim Nagi, a native Egyptian drummer, DJ, and folk dancer based in Boston. Leader of Sharq Arab Music Ensemble and the Arab Dance Seminar, Karim Nagi tours and records internationally. His design for the cover of his CD Arabized is shown here.

5:59 |

Composer: I Gdé Manik Date composed: 1940s, with frequent later revisions by composer and others; in 1952 reduced from 55 minutes to 15 minutes Date recorded: 1996 Performer: Gamelan Galak Tika, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tempo: Varies greatly, from fast (enggal or gelis) to slow (adeng or lambat) Mode: Pelog, 7-pitch tuning system Form: Klasik tari lepas, a secular, virtuosic composition in which music and dance are tightly coordinated Function: Composition for Balinese gamelan to accompany dance at festivals and competitions; showpiece for dancers and musicians Dynamics: Closely tied to tempo, with changes ranging from temporary or subtle gradations to incremental changes to interruptions |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Distinctive shimmering sound of gamelan gong kebyar, the gamelan most often heard in modern Bali

• Fast-changing combinations of melodies and textures

• Sudden changes in rhythmic patterns and tempos that define large sectional divisions, moving between faster bapang sections and alternatively slow and faster paces of lelongorran. Tempo changes are led by kendang and ugal, with kempli and other instruments keeping time.

• Intense polyphony, including interlocking parts (kotekan) played on higher-pitched metallophones (gangsa), with their combined rhythm subdividing the beat into two parts

• Dynamics and tempo as two important aspects of ensemble virtuosity and in constant flux, with no trajectory toward a single peak or climax

|

STRUCTURE AND TEXT |

DESCRIPTION |

0:00 |

Kebyar I (long) |

Instrumental introduction; literally “to flair up or burst open,” with loud, near-unison chords marking irregular rhythms. The gangsa play the melody and the reyong and ceng-ceng punctuate with crashes called byong; glissandos are heard in the gangsa. |

0:49 |

Genderan |

Contrasting section with more-flowing, polyphonic texture, regular rhythms, omitting pot gongs (reyong), drum (kendang), and cymbals (ceng-ceng) so prominent in kebyar. Beat marked by kempli and gong, with basic melody in calung, elaborated by gangsa. Dancer enters during genderan, either a young man or, more often, a young woman dressed as a youth. |

0:55 |

Kotekan begins, with one part on the beat (polos) and the other off the beat (sangsih). |

|

1:29 |

Bapang I (refers to a fast and aggressive meter, associated with strong affect or high official) |

Kotekan stops; fast gong pattern in all gongs, with two kempur strokes to one gong stroke; regular tapping pulse in kempli. Texture interrupted by angsels (sudden breaks). |

2:09 |

Bapang II |

Kotekan begins; regular tapping pulse in kempli; melody in calung, divided into four-pitch segments. |

3:40 |

Bapang I |

Each of four reyong musicians plays three pots in syncopated rhythm, with ceng-ceng punctuation, as gangsa plays brief, main melody. |

3:51 |

Lelonggoran I (slow, fast) |

Lelonggoran is based on a sixteen-beat drumming pattern, called tari lepas (hence the name of the piece’s form); this section begins quietly and at a slower tempo, as the dancer portrays the reflective, gentle side of impetuous youth, then varies in tempo through nine repetitions of the drumming patterns. |

4:01 |

Rhythmic cycle #1 |

Slows at end of cycle. |

4:05 |

Rhythmic cycle #2 |

Slows then speeds up, with angsel. |

4:24 |

Rhythmic cycle #3 |

With angsel at 4:28. |

4:38 |

Rhythmic cycle #4 |

With kotekan. |

4:47 |

Rhythmic cycle #5 |

|

4:56 |

Rhythmic cycle #6 |

Transitional, with solo by ugal at 5:05. |

5:09 |

Rhythmic cycle #7 |

|

5:25 |

Rhythmic cycle #8 |

With angsel near end. |

5:40 |

Rhythmic cycle #9 |

With kotekan and angsel near end. |

5:43 |

Kotekan |

|

5:47 |

Bapang I |

Returns briefly. |

5:52 |

|

Fade-out. |

Here in Soundscapes, we will move back and forth between traditional folk music and the closely associated folk music revivals. Both streams of tradition are present in most urban locales, where folk songs continue to be transmitted by amateurs and to be revived, transformed, and sometimes created anew by professionals.

Since the earliest days of the American folk music revival in the 1950s, Boston has been an important center for the folk music world, and many Boston singer-songwriters and musicians drew on and transformed an enormous stock of music from many ethnic communities. Boston’s long liberal tradition and the presence of so many young people at area colleges made it a magnet for the young singer-songwriters at the center of the folk music revival.

Two hundred or more venues for live folk music performance are active in the Boston metropolitan area today, including Club Passim, the successor to Club 47 in the center of Harvard Square. Irish pubs such as the Burren feature newer kinds of contemporary folk music and “roots” music, which draw on a range of American styles from Appalachian fiddling to gospel.

Try It Out |

|

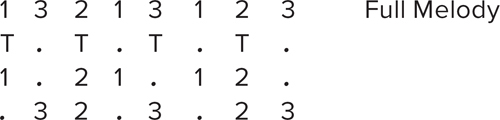

EXPERIENCE KOTEKAN

In the gamelan composition Taruna Jaya, Listening Guide 29, you have heard a technique called kotekan, literally “interlocking parts.” Two musicians playing on metallophones of the same type and size perform a single melody by dividing it between their instruments, resulting in a performance at a much faster rate of speed than either musician could have achieved alone. Kotekan thus requires collaboration between musicians, a musical process considered by many to be a metaphor for cooperation in Balinese life. Try out the exercise below so that you can experience how kotekan works. You will need to do this exercise with at least two other people since there are three separate parts. Note that you will sing the instrumental melody rather than play it.

Start by singing the full eight-beat melody, which is built from the first three notes of the scale (do-re-mi). The melody is represented by the following numbers in an eight-beat cycle:

1 3 2 1 3 1 2 3

A Balinese musician would have this entire melody in mind while playing kotekan, even though each instrument plays only half of the pitches. Sing the full melody with its numbers to establish it in your ear.

Next, designate one person as the “beat keeper” who calls out every other beat on the syllable “tok” (pronounced “talk,” represented by the letter T). Note that the periods in between the letter T indicate a silent beat, so that the beat keeper calls out “tok” on beats 1, 3, 5, and 7 of the eight-beat cycle:

T . T . T . T .

Sing the full melody accompanied by the beat keeper calling out “tok” on beats 1, 3, 5, and 7.

Next sing the first part (named the polos), which sounds only pitches 1 and 2, and starts on the first beat of the cycle:

1 . 2 1 . 1 2 .

Next sing the second part (called the sangsih), which sounds only pitches 2 and 3, and begins on the second beat of the cycle:

. 3 2 . 3 . 2 3

Now sing each melody separately with the beat keeper accompanying it.

Finally, put both the polos and sangsih together with the beat keeper. The full melody is written on top of these three parts so that you can see how your own part fits into the whole. When your three-person group has finished one eight-beat cycle, repeat it as many times as desired. Once you are all familiar with the interlocking patterns and can perform all three parts together comfortably, you can speed up the basic pulse and see how fast you can go while keeping everyone in time with the beat keeper.

Note that on beats 3 and 7, both the polos and the sangsih converge on pitch 2. If you were playing these parts on a pair of Balinese gamelan instruments tuned as customary at slightly different frequencies, you would produce a beating tone when sounding pitch 2 at the same time.

The Folk Song Society of Greater Boston, a nonprofit organization of people interested in folk music, was founded during the early years of the folk music revival in 1958–59. Today it continues as an active force, issuing a free monthly newsletter (The Folk Letter) containing a comprehensive listing of all folk music events around town. The society sponsors concerts, monthly singing parties, informal “midweek sings,” and traditional song and tune swaps, where everyone takes turns leading and exchanging songs. Most of the events are held in private homes, and people socialize over refreshments between songs.

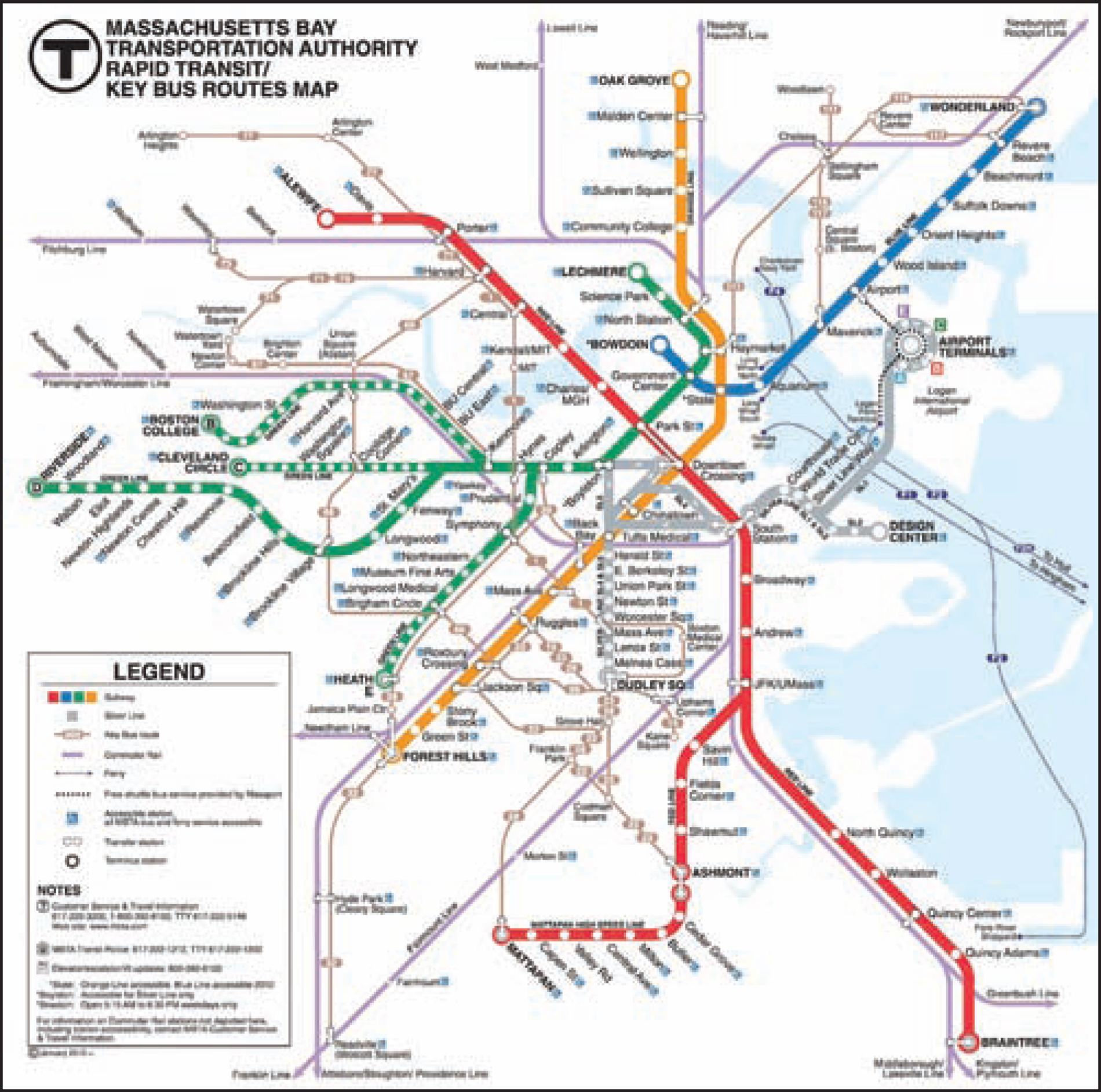

The underground trains of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), running on four color-coded lines (red, green, orange, and blue), have been immortalized in The M.T.A. Song. In 2004–2005, the MBTA opened the Silver Line, a bus rapid transit line connecting downtown Boston with Logan airport.

The accessible sounds of folk music allow almost anyone to sing along and the audience is often invited to join in on the well-known refrains of songs. Folk music continues to be attached to a variety of political causes.

The folk music movement quickly put down deep roots in Boston, and the city itself is memorialized in one of the folk revival’s most famous songs. The M.T.A. Song (referring to Boston’s Metropolitan Transit Authority) was written for the political campaign of Walter A. O’Brien, Jr., a candidate in Boston’s 1949 mayoral race. O’Brien did not win the election—indeed, he finished last—but his catchy campaign song was widely sung by folk musicians and eventually made famous through recordings, radio, and concerts.

The story behind the M.T.A. song (see Listening Guide 30, p. 114) is worth recounting here. Candidate O’Brien had objected to a five-cent raise in the M.T.A. fare. Bess Lomax Hawes and Jacqueline Steiner, the campaign workers credited with composing the M.T.A. song, borrowed a well-known melody (taken from an earlier folk song titled Wreck of the Old 97, heard in Listening Guide 8) and gave it new lyrics related to the campaign. The process of composing a new song by borrowing an existing melody and providing it with new words is found worldwide, and is particularly common in oral traditions.

During O’Brien’s campaign, sound trucks broadcast the M.T.A. song through Boston neighborhoods to advertise the campaign. According to his 1998 obituary in the Boston Globe, Sam Berman, a musician active in the campaign, recalled: “In those days, political campaigns culminated at a delicatessen in Dorchester, and different campaigns used to try and drown each other out with their sound trucks.”

The words of the M.T.A. song map Boston from the perspective of the subway that runs beneath its streets, describing areas of the city that no longer exist. For instance, Scollay Square, mentioned in verse 4, was razed in 1963 to accommodate Boston’s Government Center.

The memory of Charlie (see Listening Guide 30) has been revived in Boston with the introduction of the “CharlieCard,” a smart card that can be reused at ticket vending machines and fareboxes, and the “CharlieTicket,” a magnetically encoded ticket that contains either stored value or a T pass. In 2005, new equipment was installed throughout the Boston metropolitan area bus and subway system to accommodate the CharlieTickets and CharlieCards and to ease rider access, a rather ironic commemoration of Charlie, who was never able to get off the train. According to the MBTA website, “A large number of customers suggested CharlieCard. The naming of the card recognizes Charlie’s place in Boston’s transit history.” 33

The M.T.A. song provides insights into a changing Boston landscape while contributing to its soundscape as well. A third prominent Boston music culture, the early music movement, seeks to revive and perform music traditions from the past.

3:13 |

Date of composition: 1949 Composers/lyricists: Jacqueline Steiner and Bess Lomax Hawes Date of performance: 1959 Performers: The Kingston Trio: Dave Guard, banjo and vocals; Bob Shane, guitar and vocals; Nick Reynolds, guitar and vocals, double bass Form: Strophic song with refrain Tempo: Upbeat quadruple meter Function: Political campaign song; later popularized with new text through recordings and media |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Catchy refrain and simple strophic form, which ensure that most people who hear the song once or twice can sing along

• Use of spoken text at several points, most notably at the beginning, as well as half-spoken, half-sung speech-song in the last verses

• Blue note—a flatted-third scale step commonly used in the blues

• References to working-class Boston neighborhoods like Chelsea and Roxbury and once-familiar locations like Scollay Square

|

STRUCTURE AND TEXT |

DESCRIPTION |

|

0:00 |

Introduction Spoken: These are the times that try men’s souls. In the course of our nation’s history, the people of Boston have rallied bravely whenever the rights of men have been threatened. Today, a new crisis has arisen. The Metropolitan Transit Authority, better known as the M.T.A., is attempting to levy a burdensome tax on the population in the form of a subway fare increase. Citizens, hear me out: this could happen to you. |

The double bass sustains long, held pitches by bowing, or shakes the bow to create a tremolo, while the introductory lyric is spoken. |

0:26 |

Instrumental introduction |

Guitar accompaniment begins, followed by a syncopated banjo riff on the blue note. |

0:36 |

Verse 1 Well, let me tell you of the story of a man named Charlie On a tragic and fateful day. He put ten cents in his pocket, kissed his wife and family, Went to ride on the M.T.A. |

A fairly simple melodic structure makes the tune easy to remember: the first and third phrases of the verse are nearly identical, while the second and fourth are also quite similar to each other. |

0:49 |

Refrain Well, did he ever return? No, he never returned, And his fate is still unlearned. He may ride forever ’neath the streets of Boston, He’s the man who never returned. |

A second singer harmonizes with the lead singer in the refrain. The words “[n]ever returned” are repeated three times in each refrain, and this refrain will itself be repeated five times with small changes. The question-and-answer form of the first line is another effective rhetorical device. |

1:02 |

Verse 2 Charlie handed in his dime at the Kendall Square station, And he changed for Jamaica Plain. When he got there, the conductor told him one more nickel, Charlie couldn’t get off that train. |

The singer returns to the blue note at the beginning of the third line and near the end of the fourth line of each verse. In this verse, this occurs on the words “when” and “off that.” |

1:16 |

Refrain |

A third singer adds a comment after the second line of the refrain; this interjection varies with each repetition. |

1:29 |

Verse 3 Now all night long Charlie rides through the station, Cryin’, “What will become of me? How can I afford to see my sister in Chelsea, Or my cousin in Roxbury?” |

|

1:42 |

Refrain |

|

1:56 |

Verse 4 Charlie’s wife goes down to the Scollay Square station Every day at quarter past two; And through the open window, she hands Charlie a sandwich As the train comes rumblin’ through! |

The singer uses a vocal articulation between speech and song as he shouts out the last two lines of this verse. This technique appears again in verse 5. |

2:09 |

Refrain |

|

2:22 |

Banjo solo |

A banjo solo is added to interrupt the regularity of the verse–refrain structure. Syncopation figures prominently in the solo, and the blue note reappears at the end of the solo. |

2:35 |

Verse 5 Now, ye citizens of Boston! Don’t you think it’s a scandal, How the people have to pay and pay? Fight for the fare increase! Vote for George O’Brien! Get poor Charlie off the M.T.A.! |

Walter O’Brien’s name was changed for this recording to avoid any association with his Progressive party. O’Brien was denounced as a communist during the McCarthyite 1950s. |

2:48 |

Refrain |

The second singer jumps to a higher register to sing a slightly different harmonization for the last repetition of the refrain. The final line is repeated an extra two times to bring the song to a close. Note the spoken “Et tu, Charlie?” at the very end of the track, which concludes at 3:13. |

EARLY MUSIC The third distinctive Boston soundscape is the lively world of early music, a domain in which musicians play repertories from the past on reconstructed instruments, aspiring to revive the sounds and styles of earlier eras. This interpretation is sometimes termed historically performed performance practice.

Boston provided all the ingredients that allowed early music to flourish. The first center of European music in the United States, the early Boston community supported ensembles such as the Handel and Haydn Society, which was founded by a group of local merchants in 1815 and still survives today.