LISTENING FOR MUSICAL TEXTURE AND FORM

Throughout the previous pages, we have discussed the characteristics of sound as separate elements. But as we have returned repeatedly to the same musical examples for illustrations of different sound characteristics, it has no doubt become clear that all the aspects of sound interact. Indeed, it is only when quality, intensity, pitch, and duration combine that we are really experiencing music. How can we think about and talk about the different ways in which the characteristics of sound are organized on a larger scale? We can first consider the vertical structure of music, called texture, and then move on to form, the overall organization of music shaped as the characteristics of sound interact over time.

HEARING AND COMPARING TEXTURES

Musical texture results from the ways in which instruments and/or voices combine with each other.

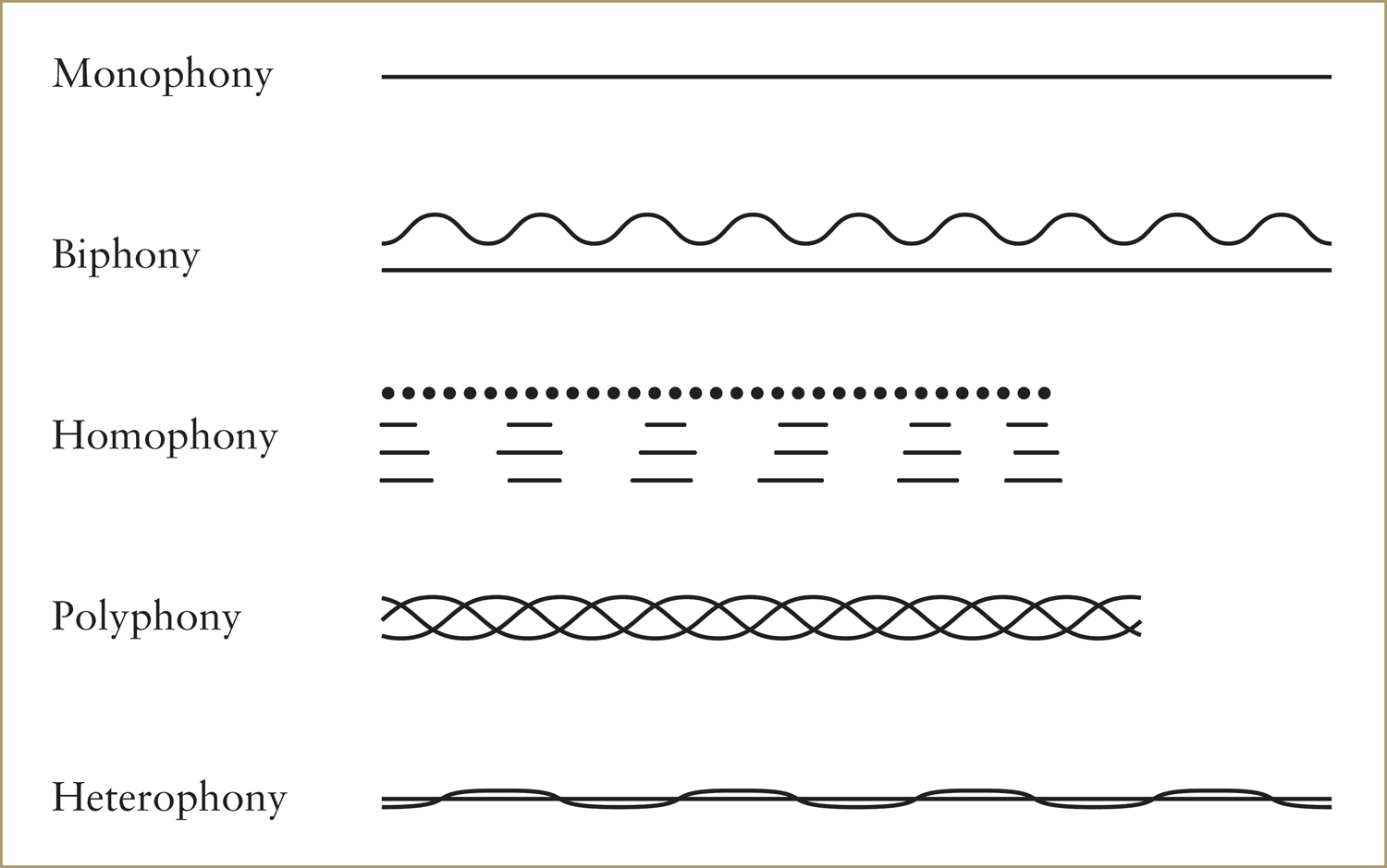

There are five major categories of musical texture, the names of which are based on the root “phone,” derived from a Greek word meaning “voice” or “sound.” These textures, which include monophony, biphony, homophony, polyphony, and heterophony, are summarized by line drawings in the following figure.

The simplest musical texture is monophony, literally a “single sound.” A texture is monophonic when an individual voice or melody instrument performs alone (solo), or when more than one voice or instrument sing or play the same melody together, sounding the same pitch in the same rhythm at the same time. Listen again to Harmonic Opening in Listening Guide 5, where the first minute of that recording features David Hykes performing a solo chant melody in a clear example of monophony. Other examples of monophony are heard in two solo examples of an Ethiopian chant in Chapter 8. A single voice (except in the case of khoomii singing) constitutes a monophonic texture, as does a group of voices singing together on exactly the same pitch, in the same rhythm.

A biphonic texture has two distinct lines, the lower sustaining a continuous pitch (drone) while the other performs a more elaborate melody above it. We heard two Armenian duduks playing in a biphonic texture in Listening Guide 11; in Listening Guide 12, the sitar and an accompanying drone produce a biphonic texture.

Sometimes a single voice or instrument can produce a biphonic texture by itself, as we have seen in the case of khoomii singing in Listening Guide 5. In Chapter 3 we will explore the sound of the bagpipe, which on its own sounds a biphonic texture consisting of drones and a melody.

Homophony, a “same sounding” texture, occurs when a melody is supported by other vocal or instrumental parts, all of which move along in roughly the same rhythm as the melody, but on different pitches. Barbershop quartets and church choirs usually sing in homophony, often referred to as “four-part harmony.” This texture, common in Euro-American traditions, usually has one voice part, often the highest of the four parts, singing the melody while the other parts sing the same words in the same rhythm, but on different pitches that combine with the melody to form chords, the individual units of Western harmony.

STUDYING MUSIC |

|

THINKING ABOUT “WESTERN MUSIC”

We have noted throughout Chapter 1 the influence of Western ideas and values on musical terminology. Any discussion of music traditions must also take into account the impact of Euro-American musical sounds, repertory, ensembles, and concepts—often lumped together under the term “Western music”—on so many aspects of music worldwide. Ironically, while “Western” is most commonly used to describe European and American art music of the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, Western music actually consists of many different styles of musical expression from many parts of Europe, and later from North, Central, and South America. We will frequently encounter traces of Euro-American musical sounds and concepts in the soundscapes we study.

Western musics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries share a music system termed tonal music, in which a single pitch or tone serves as the point of departure and return in any piece of music. As explained in the figure on page 45, the Western tonal system divides the octave into twelve pitches, each of which can serve as the first and last pitch—the center of gravity—for groupings of pitches into scales.

Initially, Western music traveled to different locales along with European missionaries and colonists. In the United States, this imported music tradition quickly established deep roots, supported by an elite dominated until the late nineteenth century by people of European descent. The international impact of the United States in twentieth-century economic and political life, along with the growth and international spread of the US recording industry, also served to disperse Western musical sounds worldwide.

European repertories such as the symphony and opera were transplanted and taken in innovative directions in the New World; at the same time, new American musical idioms interacted with elements of the Western musical system. The extraordinary array of African American musics that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including ragtime, blues, and jazz, drew on some aspects of the Western music system, transforming them to create new genres.

Throughout the world in the twentieth century, many primary and secondary schools taught Western music. These shared musical experiences in schools and the pervasive presence of Western popular music on the radio are the reasons many around the globe have at least a passing familiarity with Western tonal music.

The American folk song Wreck of the Old 97 (Listening Guide 8) provides another example of homophony; the singer performs the words and melody and the guitar provides supporting harmony as accompaniment. Homophony occurs frequently in European and American folk musics.

The mbalax band Nder & le Setsima Group, featuring vocalist Alioune Mbaye Nder, is pictured here performing at the Parc de la Villette, Paris, in August 1998. Instruments include synthesizer, bass guitar, and drums. On the right side of the photo, percussionist Lamine Touré is playing the drums: the sabar, which is prominently displayed, and the djembe drum, half hidden behind the sabar.

Combinations of more than one voice or instrument can create textures called polyphony, literally “many sounds.” There are many different types of polyphonic textures, some examples of which we’ve already encountered. The katajjaq in Listening Guide 6 is a good example of two-part polyphony, in which two separate but very similar vocal lines interweave and interact with each other.

The song Lenëën in Listening Guide 17 (see p. 54) provides an example of multipart polyphony, with different instruments and voices constantly interweaving different melodies and rhythms. In Senegal since the 1970s, the sabar drum, heard earlier in Listening Guide 14, has been an increasingly important member of popular music ensembles such as the mbalax dance music in Listening Guide 17, a style named after a well-known sabar drum rhythm.

The polyphonic texture of Lenëën is enhanced by many contrasting rhythms, called polyrhythms. The two sabar drums establish a fast-changing rhythmic dialogue; as one drummer plays a bass beat and intermittently performs traditional sabar rhythms (bàkks), the other moves between several drums of different sizes and shapes to provide a wider range of rhythms and tone qualities. Both drums play against the quadruple meter established by the synthesizer and bass, following an introduction with a free rhythmic structure. Throughout the song, the voice, saxophone, and trumpets enter and exit, adding their own distinctive rhythms to the texture. Within this multilayered, polyphonic music, Senegalese audiences recognize familiar bàkks, such as bàkk Lenëën, which are played during instrumental interludes or between verses by a solo sabar drum.16

While polyphony generally occurs when several voices or instruments perform different melodies or different rhythms together, some instruments, such as the piano, the accordion, and some zithers, have the capability to produce multiple musical lines on their own.

2:41 |

Date of recording: 2000 Performers: Nder & le Setsima Group; Alioune Mbaye Nder, lead vocal; Saliou Ba, bass; Malick Diaw, guitar; Bassirou Mbaye and Mokhtar Samba, drums; Talla Seck and Lamine Touré, percussion; Ibou Tall, Elou Fall, and Jean-Phillipe Rykiel, keyboards; Ibou Konaté, trumpet; Mor Sarr, saxophone; Aïcha Konte and Mbene Seck, backup vocals Composer: Alioune Mbaye Nder Tempo: Moderate tempo, quadruple meter Function: Nightclub entertainment and dance accompaniment |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Five separate but interacting melodic/rhythmic parts played by (1) the saxophone, (2) synthesizer and bass accompaniment, (3) sabar drums, (4) trumpets, and (5) voice

• Repeating harmonic pattern in the synthesized vibraphone, which alternates every measure between only two chords

• Entry of Lenëën bàkk at 2:16

STRUCTURE AND TEXT |

TRANSLATION |

DESCRIPTION |

|

0:00 |

Introduction |

|

A synthesizer carries the melody |

0:14 |

|

|

Electric bass and trumpets |

0:30 |

Verse |

|

The lead vocalist begins the first |

0:49 |

Bala nga koy xam |

Before you know it |

The backup singer adds a brief |

1:07 |

Weetay bi gënn bonn moy, |

The worst of loneliness |

The singer introduces a new |

1:33 |

Chorus |

|

A short phrase is repeated four |

1:49 |

Setlul bu baax, jigeen yalla ko |

Look carefully, God honored |

Chorus continues with different |

2:16 |

Bàkk |

|

A solo sabar enters playing the |

2:35 |

|

|

Fade-out. |

Transcription and translation by Patricia Tang and Papa Abdou Diop

In musical traditions of the Middle East and parts of Asia, one frequently encounters a distinctive texture called heterophony, produced by several voices or instruments that perform similar but slightly different melodies and rhythms at the same time. Heterophonic textures can be heard in the Mongolian long song (Listening Guide 7), in which the female voice and fiddle perform in near unison, with slight differences in melody and rhythm.

A large instrumental ensemble of the Naxi people in China’s southwestern Yunnan Province performs in heterophony in Listening Guide 18 (see p. 56). This instrumental ensemble, which plays at rituals celebrating festivals of various religious deities, includes several aerophones, three different kinds of plucked lutes, bowed two-stringed instruments, and various membranophones and idiophones. When these instruments perform together, all play the same melody with slightly different ornaments.

1:19 |

Date of recording: 1995 Performers: The Dayan Ancient Music Association Function: Before 1949, performed at rituals and festivals for deities, as well as by amateur groups for entertainment; since 1949, primarily played for entertainment |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The ways in which playing techniques (whether blowing, plucking, or bowing) shape the melody differently

• Melodic differences, depending on what is possible or comfortable. Higher-pitched lutes here use elaborate ornaments, while the lower, double-reed pipe plays the melody more simply

• The yinqing, an inverted clapperless bell on a stick that is struck with a metal beater, making a tinkling sound that reinforces the beat throughout

• Subtle differences between instrumental parts by following continuously one distinctive instrumental timbre (whether flute, double-reed pipe, plucked or bowed lute) throughout the example

STRUCTURE AND DESCRIPTION |

|

0:00 |

Flute (dizi) enters, joined almost immediately by a high-pitched lute. Then other bowed lutes, plucked lutes, one plucked zither (zheng), and a double-reed pipe (bobo) enter, the latter quite hard to hear as it pulsates from time to time on sustained pitches. |

0:13 |

A low, plucked chordophone (pipa) enters, reinforcing important pitches of the melody. |

0:15 |

The pipa emphasizes subdivisions of the basic pulse. |

0:32 |

Intense heterophony occurs at the highest points in the melody as several instruments seem to strain to reach the pitch. (Also occurs at 0:14, 0:38, etc.). |

One type of texture may be maintained throughout a song or instrumental piece, but texture can also vary. Indeed, music would become tedious if it remained the same in all characteristics of sound throughout. Most music therefore changes as it moves through time, varying the relationship between the sound sources, melodies, rhythms, and intensity, shaping textural changes in ways that are familiar within a given music tradition.

HEARING AND COMPARING FORMS

When we speak of the shape or structure of music, we are referring to form. When a text is present, one can often identify the form by looking at the relationship of melody to text. For instance, returning to Listening Guide 8, the folk song Wreck of the Old 97, one hears a musical structure that follows clearly delineated verses or strophes of text; each subsequent strophe is set to the same music. This form is called strophic structure. Strophic structures are very common across historical epochs and geographical and cultural boundaries. Many folk and popular songs have strophic structures in which the verses alternate with a recurring chorus, called a refrain, that repeats both the same music and the same text. The M.T.A. Song heard in Listening Guide 30 (in Chapter 2) is a strophic folk song with a catchy refrain.

Many forms are named, such as the strophic vocal form that tells a story, known as the ballad, which we will study in Listening Guides 31 and 32 (in Chapter 2). Forms of instrumental music tend to vary between music traditions. In the absence of text, one has to listen closely to the characteristics of sound to follow the form of an instrumental composition. Many forms become conventional through frequent use over time and are identified by name, such as the sama‘i, a lively Middle Eastern instrumental piece.

“This one goes verse, verse, chorus, train; verse, verse, chorus, train.”

The word sama‘i means “heard,” and refers to being audible.17 The sama‘i in modern Middle Eastern music is an instrumental overture with four parts. Each of the four parts is called a khanah (pl., khanat), and is separated from the other khanat by a refrain, a section of music (and, in vocal music, text) that recurs. The sama‘i is usually played by a Middle Eastern ensemble that may vary in size but generally includes one or more violins, plucked lutes (‘ud), a zither (qanun), a goblet-shaped drum (darabukkah or tablah), a frame drum (riqq), and a flute (nay or ney); it can also be played by a soloist. Next we explore Sama‘i Bayyati (see Listening Guide 19, p. 58); the word bayyati in the work’s title indicates that it is performed in the Middle Eastern musical category or mode (maqam) of that name. Maqam bayyati is based on a seven-pitch scale in which the second and sixth pitches are inflected distinctively. The sama‘i has a standard rhythmic profile: it uses the same rhythmic organization for the first three khanat and a different rhythm for the fourth khanah. The first three khanat are in a slow rhythm known as sama‘i thaqil (“heavy”) which divides into ten-beat patterns; the fourth and final khanah is performed in faster, six-beat units that can be heard as a strong two-beat pattern.

Throughout the book, we will encounter many other examples that will help us listen for and recognize a wide array of musical forms. Here we will explore the creative processes that create form.

1:19 |

Date of recording: 1995 Performers: University of California, Santa Barbara, Middle Eastern Ensemble, Scott Marcus, director Form: Sama‘i, an instrumental composition with four parts (four khanah, pl., khanat) separated by refrains Composer: Ibrahim al-‘Aryan (1898–1953) Function: Performed before a suite or for pedagogical purposes |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The form of the sama‘i, which is outlined below. The beginning of Khanat 2, 3, and 4 are signaled by a change in texture and the sounding of the tablah drum.

STRUCTURE |

DESCRIPTION |

|

0:00 |

Khanah 1 |

This khanah introduces the sama‘i, setting forth the content of maqam bayyati. |

0:28 |

Refrain |

The refrain, itself repeated, repeats a descending phrase several times, before ascending to a high point and then descending to the central pitch. |

1:22 |

Khanah 2 |

Khanah 2 focuses on a higher register of the maqam than the previous khanah or the refrain. |

1:48 |

Refrain |

|

2:41 |

Khanah 3 |

Khanah 3 remains in the higher register of the maqam and moves in conjunct motion up and down the scale of maqam bayyati, touching briefly on another maqam, ajam, from 2:52 to 3:00. |

3:07 |

Refrain |

The qanun can be heard playing an ascending scale at 3:32 just before the refrain is repeated. |

4:00 |

Khanah 4 |

Note change in rhythmic pattern and faster tempo for Khanah 4, which also includes marked changes in texture, with repeated “calls” and “responses” between different instruments. |

4:49 |

|

The pace slows markedly, leading back to the refrain. |

4:53 |

Refrain |

The instruments slow down at the end and the flute plays a descending scale to bring the piece to a close at 5:51. |