CONCLUSION

Repeated listening to music, primarily through the medium of sound recordings, enables us to develop listening skills, a process discussed in “Studying Music: Tips on How to Listen,” see p. 66).

Although recorded sound has helped us launch our exploration and has allowed us to study and appreciate a vast range of musical creativity, we must now turn to the settings in which musical sound is transmitted and performed. In this way, we can expand our understanding of the importance of place to many music traditions and the contributions that musical creativity makes to the settings of which musicmaking is a vital part.

FURTHER FIELDWORK |

|

An integral part of doing fieldwork is the process of recording sound. In addition to recording interviews in the field, ethnomusicologists record live musicmaking. You have probably noticed that each of the recordings in the Listening Guides in this chapter sound subtly different from each other. They were recorded at different points in time, in different places, and on various types of equipment then available. As a result, for example, the vintage field recordings of the steel band in Dominica and the Bahamian sponge gatherers embed the technological limitations of their eras as well as include sounds of the environments in which they were recorded. In contrast, examples such as Brubeck’s Blue Rondo à La Turk, even though it dates from the late 1950s, reflects the more pristine environment of the sound studio of that era as well as subsequent remastering processes.

Whenever one is recording a live musical event, ambient sounds, whether a rustle of a program at a concert or a random cough by a participant, become part of the acoustical record. In recent years, especially under the influence of R. Murray Schafer discussed in Soundscapes’ Introduction, many ethnomusicologists and composers have turned their attention from recording musical performance to capturing extramusical sounds of various urban and rural locales. You have already encountered a few such examples in the Introduction, ranging from bells and traffic in New York City to water drumming in Indonesia. Many ethnomusicologists are entering into this lively new world of sound and critical media studies, which is accessible through free and open online journals (such as Sensate) that explore the growing field of experimental media studies and provides critical discussion of new forms of sound scholarship. Some scholars are moving into a new allied field called “acoustemology,” which explores how to know a place through its sonic features.20 You can also visit the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings online at sounds.bl.uk and explore the wide range of sounds, environmental and musical, stored there. It is possible to browse the collection by map, sound, archive collection, and location.

As you visit these sites, consider what recordings you might make of your own local soundscapes and their musical lives. In this chapter’s “Individual Portraits,” you read how composer Pauline Oliveros would place a small recorder on her window ledge to capture the sounds in and around her San Francisco home. What sounds might you record as part of your own further fieldwork? Be sure that you consider carefully what you record and obtain permission from anyone else involved.

STUDYING MUSIC |

|

TIPS ON HOW TO LISTEN

Using your knowledge of the characteristics of sound can help you make sense of any music tradition you encounter. Now that you are familiar with the categories of quality, intensity, pitch, and duration, try to incorporate consistently each characteristic and its associated terminology into your own listening process.

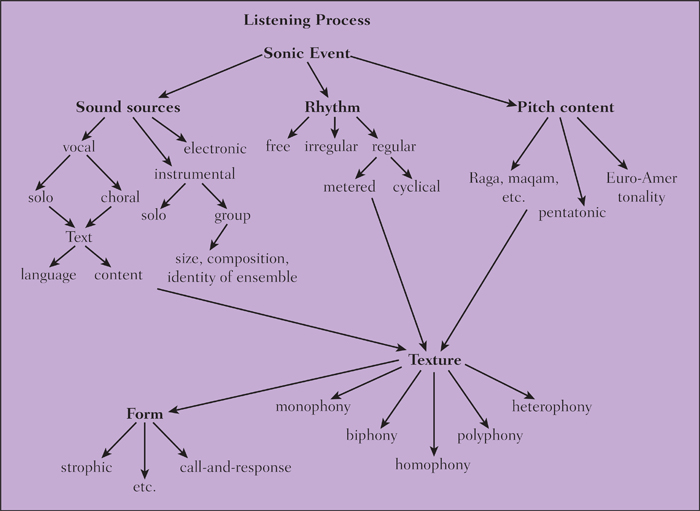

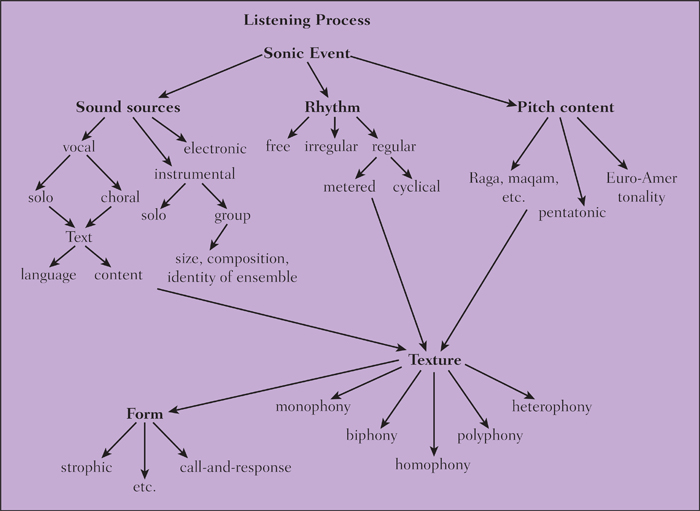

One such process is summarized in the following figure, a mental checklist that can guide you when you are confronted with unfamiliar music. It is usually most efficient to begin with quality—first identifying the sound source(s) performing—but it is best for you to decide in what order you will proceed through the characteristics of sound. It is helpful for an inexperienced listener to settle on a particular sequence of characteristics in order to systematically develop your listening skills and to have an analytical framework to fall back on if you are perplexed by what you hear. Depending on your musical background and listening experience, you may find it easier to focus first (after quality) on rhythmic aspects, while another person may feel more at home focusing on pitch organization.

As you become a more experienced listener, you will find that identifying a sound source and one other prominent factor related to pitch, rhythm, texture, or form, will provide a strong indication of what you are hearing. For instance, if you encounter an ‘ud (Middle Eastern lute) playing in a heterophonic texture, you should suspect that you are hearing music with its roots in Middle Eastern traditions. At this point, focusing on a third characteristic, such as pitch or rhythmic content, can either confirm your analysis or raise further questions. As you proceed through this book and gain experience listening to music from many different soundscapes, you will also develop your own memories of sounds ranging from the Indonesian gamelan to West African drumming, which will build your personal sound archive against which new sounds can be compared.

Guide to the listening process.

IMPORTANT TERMS

silence

music

sound sources

quality or timbre

vibrato

straight tone

raspy

chest voice

head voice

falsetto

nasal

intensity

pitch

range

intervals

scale

melody

conjunct

disjunct

ornaments

phrase

duration

pulse

beat

rhythm

tempo

meter

measure

simple meter

compound meter

accent

syncopation

irregular rhythm (meter)

free rhythm

organology

Sachs-Hornbostel system

idiophones

chordophones

lute

harp

lyre

zither

aerophones

membranophones

electrophones

texture

monophony

biphony

homophony

polyphony

heterophony

form

strophic

refrain

composition

improvisation

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS

Reading

For more details about composer Pauline Oliveros, whose innovative work with sound is discussed in “Individual Portraits,” see her books, most recently Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice, released in 2005. For more information about the many musical styles briefly discussed in Chapter 1, consult The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, a ten-volume reference work that is organized geographically and available in most libraries and also online.

Viewing

Hans Fjellestad’s 2005 documentary Moog provides an introduction to the life and work of Robert Moog, the inventor and builder of the first electronic musical instruments. Both vocal techniques and the place of a distinctive vocal style in a range of cultural settings are the subjects of Hugo Zemp’s four films in A Swiss Yodelling Series: “Jüüzli” of the Muotatal. Don’t neglect to visit the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings online (see p. 65).

Listening

Performances by most instruments and of most musical styles can be easily accessed online by searching under the name of the instrument (such as didjeridu, sitar, or sabar) or style (wangga song, raga, mbalax). Organizations that transmit and perform specific musical traditions often have their own information-rich websites. For instance, see the Dayan Ancient Music Association from China and postings of the Armenian Duduk Society.

Steven Feld, “Waterfalls of Song: An Acoustemology of Place Resounding in Bosavi, Papua New Guinea,” in Senses of Place, ed. Steven Feld and Keith H. Basso (Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 1996), pp. 97–98.

silence The absence of sound.

music The purposeful organization of the quality, pitch, duration, and intensity of sound.

sound sources The voices and instruments that produce musical sound and whose vibrations give rise to our perceptions of quality.

quality The color of a sound, arising from acoustical properties of the harmonic series. Also called timbre.

vibrato A regular fluctuation of a sound, produced by varying the pitch of the sound.

straight tone Vocal style sung without audible vibrato.

raspy A singing voice that is rough or gruff in quality.

chest voice Sound resonated from within the chest, with a low, powerful, throaty vocal quality.

head voice A light, bright, high tone resonated in the head.

falsetto The process of singing by men in a high register above the normal male singing range.

nasal A buzzing vocal quality produced by using the sinuses and mask of the face as sound resonators.

intensity The perceived loudness or softness of a sound.

pitch The highness or lowness of a sound.

range The distance between the highest and lowest pitches that can be sung or played by a voice or instrument.

intervals The distance between two pitches.

scale A series of pitches set forth in ascending or descending order.

melody A sequence of pitches, also called a tune, heard in the foreground of music.

conjunct Stepwise melodic movement using small intervals, as opposed to disjunct motion.

disjunct Melodic motion by leaps of large intervals, as opposed to conjunct motion.

ornaments Melodic, rhythmic, and timbral elaborations or decorations such as gracings, rekrek, and grace notes.

phrase A brief section of music, analogous to a phrase of spoken language, that sounds somewhat complete in itself, while not self-sufficient. One phrase may be separated from the next by a brief pause to allow the singer or player a moment to breathe.

duration The way music organizes time; can be described in terms of rhythm, pulse, and meter.

pulse The short, regular element of time that underlies beat and rhythm.

beat An individual pulse.

rhythm The temporal relationships within music.

tempo Music’s rate of speed or pace.

meter A term describing the regular pulse of much of Western classical music and its divisions into regular groupings of two, three, four, or six beats.

measure The unit of time in Western music and musical notation in which one grouping of the meter takes place.

simple meter Groupings of two, three, or four beats per measure.

compound meter Groupings of six, nine, or twelve beats per measure.

accent Emphasis on a pitch by any of several means, such as increased intensity, altered range, or lengthened duration.

syncopation A rhythmic effect that provides an unexpected accent, often by temporarily unsettling the meter through a change in the established pattern of stressed and unstressed beats.

irregular rhythm (meter) Asymmetrical groupings with different numbers of beats per measure.

free rhythm Rhythm that is not organized around a regular pulse.

organology The study of musical instruments.

Sachs-Hornbostel system A classification of musical instruments, named after the scholars who developed the system.

idiophones Instruments that produce sound by being vibrated. One of the five main classes of instruments in the Sachs-Hornbostel system, idiophones are further classified by the way they are caused to vibrate: concussion, struck, stamped, shaken, scraped, plucked, or rubbed.

chordophones Instruments with strings that can be plucked or bowed, one of the five main classes of instruments in the Sachs-Hornbostel system, which subdivides them into lutes, harps, lyres, and zithers.

lute Chordophone whose strings are stretched along a neck and body, such as the ‘ud, ukulele, and guitar.

harp Chordophone whose strings run at an angle away from the soundboard, subcategorized by shape, playing position, and tunings.

lyre Chordophone whose strings are stretched over a soundboard and attached to a crossbar that spans the top of a yoke.

zither A chordophone without a neck or yoke whose strings are stretched parallel to the soundboard.

aerophones Instruments that sound by means of vibrating air; one of the five main classes of instruments in the Sachs-Hornbostel system, subdivided into trumpets and horns, pipes (flutes and reeds), and free aerophones.

membranophones Instruments whose sound is produced by a membrane stretched over an opening. One of the five main classes of instruments in the Sachs-Hornbostel system, membranophones are distinguished by their material, shape, number of skins (or heads), how the skins are fastened, playing position, and manner of playing.

electrophones Instruments that produce sound using electricity, one of the five main classes of instruments in the Sachs-Hornbostel system, subdivided into electromechanical instruments, radioelectric instruments, and digital electronic instruments.

texture The perceived relationship of simultaneous musical sounds.

monophony Literally, a “single sound”; a single melodic line sounded by one voice or instrument, or more than one, sounding the same melody at the same time.

biphony A two-voiced texture in which the lower part sustains a continuous pitch (drone) while the upper part sounds a melody.

homophony A musical texture in which two or more parts sound almost the same melody at almost the same time; often with the parts ornamented differently.

polyphony A musical texture in which two or more parts move in contrasting directions at the same time.

heterophony A musical texture in which two or more parts sound almost the same melody at almost the same time; often with the parts ornamented differently.

form The structure of a musical piece as established by its qualities, intensities, pitches, and durations, typically consisting of distinct sections that are either repeated or are used to provide contrast with other sections.

strophic A form in which all verses of text are set to the same melody. Strophic form can include a refrain that is sung between verses.

refrain A fixed stanza of text and music that recurs between verses of a strophic song.

composition The process of creating music. Also, the end product of the process—the piece that is composed.

improvisation The process of composing music as it is performed, drawing on conventions of preexisting patterns and styles. Examples include cadenzas, jazz riffs, and layali.