PROCESSES OF MUSICAL CREATIVITY: COMPOSITION, PERFORMANCE, IMPROVISATION

The distinctive sounds, textures, and forms of a particular music tradition arise from several interconnected processes of human creativity. Composition is a term for the process of creating music; an individual who creates music is known as a composer. In many traditions, however, a composition assumes its shape only during the course of performance. This process is sometimes referred to as improvisation, which can be defined as the spontaneous creation of music during performance. Although composition and improvisation have been separated in Western musical thought and approached as mutually exclusive processes, this is a misleading dichotomy. All musical performances incorporate at least some degree of creativity. Similarly, improvisation does not emerge from a void but is based in large part on the musician’s prior musical knowledge and experience. Even in those music traditions that separate composition from performance and have detailed systems of music writing, the performer still retains at least some creative latitude. In sum, we can say that improvisation is the spontaneous composition of music in time.

Some twentieth-century composers have practiced spontaneous composition; we see an example in the music of Pauline Oliveros (see “Individual Portraits: Pauline Oliveros’s ‘Deep Listening,’ ” p. 61).

Many compositional processes exist in various cultures. For instance, Australian wangga songs (Listening Guide 13) are owned by individuals who compose songs in several different ways. Most songs are received by a songman from spirits during dreams or other altered states, but it is also possible for a singer to conceive a song without the inspiration of a spirit. Songs may also be inherited from someone else, usually the songman’s father.18

It may be helpful to think about musical performance as requiring a continuum of choices, some made prior to performance, others made in the moment. Before the performance, musicians decide what instruments or voices to use and how closely to follow musical notation. During the performance, more choices are made. These might range from subtle decisions about aspects of musical pace to choices about altering a melody or rhythm through ornaments or syncopation. In addition, the performers might need to substitute a different voice or instrument because of unexpected acoustical factors or a broken string.

We will explore choices made before and during musical performance throughout the book. We will find that the length of a musical performance can be flexible, determined by the constraints of the occasion on which the music is played. We will explore settings of musical performance more closely in Chapter 2, but we’ve already encountered examples such as the Mbuti musical bow tune (Listening Guide 9), and the steel band music (Listening Guide 10), which can be sustained as long as the performers choose and the audience is willing to listen. Contrast these examples to Sama‘i Bayyati (Listening Guide 19), which, while a relatively fixed form, retains some flexibility. The musicians can ornament their melodies differently in each performance, and sections within the khanat can be repeated.

The Middle Eastern Ensemble of the University of California, Santa Barbara was founded in 1989 by ethnomusicology professor Scott Marcus. In the front row, two men and a woman play ‘uds; the second lute from the left is the Turkish cümbüs. On the far right of the first row, a woman plays the qanun and sings. Musicians in the back row, from left to right, include two ‘ud players, a violist, a violinist, and a singer.

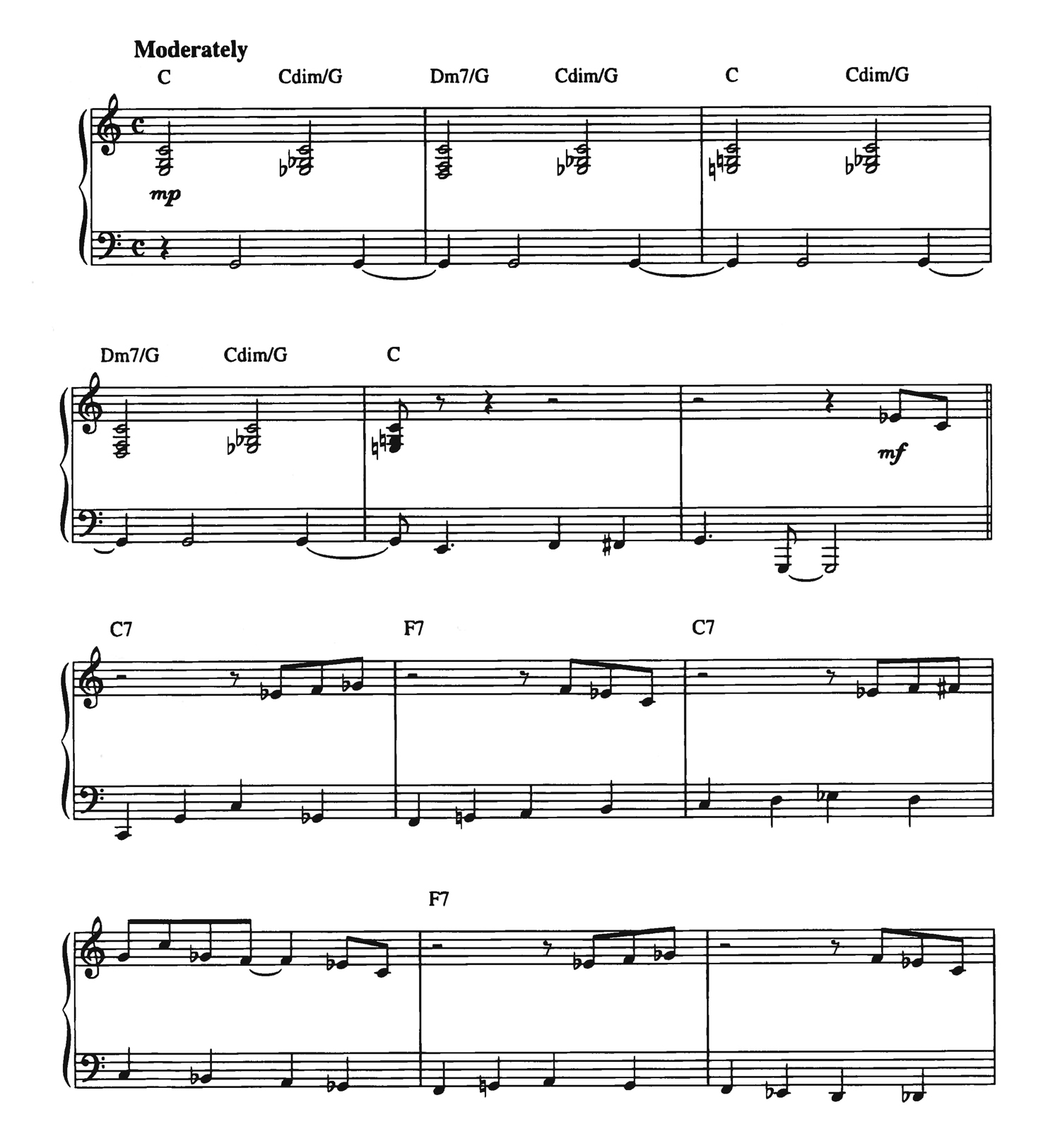

Lead sheets supply all the information necessary to perform popular and jazz tunes. The melody (usually written on the treble-clef staff) is either sung or played by a melody instrument such as a trumpet. Information about the bass or root movement is supplied by the chord symbols, which also indicate the harmonic possibilities to the keyboard or guitar players. This example shows the opening page of Splanky by Neal Hefty.