Effects of the Mongol Conquests and Their Significance

Effects of the Mongol Conquests and Their Significance

THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE REORIENTATION OF THE WEST

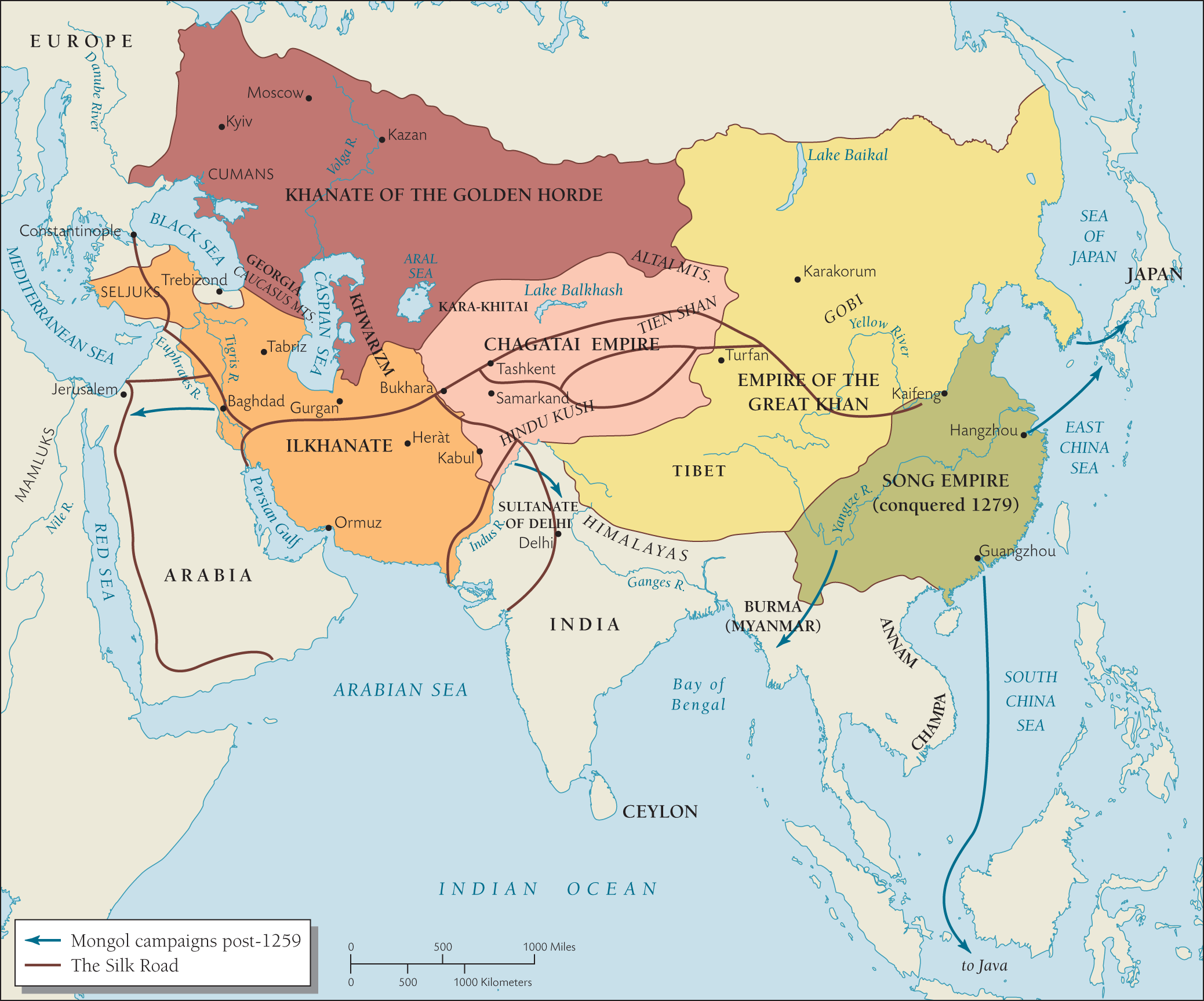

In our long-term survey of Western civilizations, we have frequently noted the existence of strong links between the Mediterranean world and the Far East. Trade along the network of trails known as the Silk Road can be traced far back into antiquity, and we have seen that such overland networks were extended by Europe’s waterways and by the sea. But it was not until the late thirteenth century that Europeans were able to establish direct connections with India, China, and the so-called Spice Islands of the Indonesian archipelago. For Europeans, these connections would prove profoundly important, as much for their impact on the European imagination as for their economic significance. For the peoples of Asia, however, the more frequent appearance of Europeans was less consequential than the events that made these journeys possible: the rise of a new empire that encompassed the entire continent.

The Expansion of the Mongol Empire

The Mongols were among many nomadic peoples inhabiting the vast steppes of central Asia. Although closely connected with the Turkish populations with whom they frequently intermarried, the Mongols spoke their own distinctive language and had their own homeland, located to the north of the Gobi Desert in what is now known as Mongolia. Essentially, the Mongols were herdsmen whose daily lives and wealth depended on the sheep that provided shelter (sheepskin tents), woolen clothing, milk, and meat; but they were also highly accomplished horsemen and raiders. Indeed, it was to curtail their raiding ventures that the Chinese had fortified their Great Wall many centuries before. Primarily, though, China defended itself from the Mongols by attempting to ensure that the Mongols remained internally divided, with their energies turned against each other.

In the late twelfth century, however, a Mongol chief named Temujin (c. 1162–1227) began to unite the various tribes under his rule. He did so by incorporating the warriors of each defeated tribe into his own army, gradually building up a large and terrifyingly effective military force. In 1206, his supremacy over all these tribes was reflected in his new title: Genghis Khan (from the Mongol words meaning “universal ruler”). This new name also revealed his wider ambitions and, in 1209, Genghis Khan began to direct his enormous army against the Mongols’ neighbors.

Taking advantage of the fact that China was then divided into three warring states, Genghis Khan launched an attack on the Chin Empire of the north and managed to penetrate deep into its interior by 1211. These initial attacks were probably looting expeditions rather than deliberate attempts at conquest, but their aims were soon sharpened under Genghis Khan’s successors. Shortly after his death in 1227, a full-scale invasion of both northern and western China was under way. In 1234, these regions also fell to the Mongols. By 1279, one of Genghis Khan’s numerous grandsons, Kublai Khan, would complete the conquest by adding southern China to the empire.

For the first time in centuries, China was reunited, although under Mongol rule. It was also connected to western and central Asia in ways unprecedented in its long history, because Genghis Khan had brought crucial commercial cities and the Silk Road trading posts (Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara) into his empire. Building on these achievements, one of his sons, Ögedei (EHRG-uh-day), laid plans for an even farther-reaching expansion of Mongol influence. Between 1237 and 1240, the Mongols under his command conquered the Rus’ capital at Kyiv and then launched a two-pronged assault directed at the rich lands of the European frontier. The smaller of the two Mongol armies swept through Poland toward Germany; the larger army went southwest toward Hungary. In April 1241, the smaller Mongol force met a hastily assembled army of Germans and Poles at the battle of Legnica in southern Poland, where the Mongols were driven back at the cost of many lives on both sides. Two days later, the larger Mongol army annihilated the Hungarian army at the river Sajo. It could have moved even deeper into Europe after this important victory, but it withdrew when Ögedei Khan died in December of that year.

Muscovy and the Mongol Khanate

The capital of Rus’ at Kyiv had fostered crucial diplomatic and trading relations with both western Europe and Byzantium, as well as with the Islamic caliphate at Baghdad. But that dynamic changed with the arrival of the Mongols, who shifted the locus of power from Kyiv to their own settlement on the lower Volga River. From there, they extended their dominion over a vast terrain, stretching from the Black Sea to central Asia. It became known as the Khanate of the Golden Horde, a name that captures the striking impression made by the Mongol tents, which literally shone with wealth because many were hung with cloth of gold. (The word horde derives from the Mongol word meaning “encampment” and the related Turkish word ordu, “army.”)

Initially, the Mongols ruled Rus’ lands directly, installing their own administrative officials and requiring local princes to show their obedience to the Great Khan by traveling in person to the Mongol court in China. But after Kublai Khan’s death in 1294, the Mongols began to tolerate the existence of several semi-independent principalities from which they demanded regular tribute. Kyiv did not recover its dominant position, but one of these principalities, the duchy of Moscow, gained new political and economic prominence due to its strategic geographical location. Moscow became the tribute-collecting center for the Mongol Khanate, and so was supplied with resources to defend itself against attack. Its dukes were even encouraged to extend their lordship to neighboring territories in the region in order to increase its security. Eventually, the Muscovite dukes came to control the khanate’s tax-collecting mechanisms. As a reflection of these extended powers, Duke Ivan I (r. 1325–1340) gained the title Grand Prince of Rus’. When the Mongol Empire began to disintegrate, the Muscovites were therefore in a strong position to succeed their former overlords.

The Making of the Mongol Ilkhanate

As Ögedei Khan moved into the lands of Rus’ and eastern Europe, Mongol armies were also sent to subdue the vast territory that had been encompassed by the former Persian Empire, then those by the empires of Alexander and Rome. Indeed, the strongest state in this region was known as the sultanate of Rûm (the Arabic word for “Rome”). This Sunni Muslim sultanate had been founded by the Seljuk Turks in 1077, just prior to the launching of the First Crusade, and consisted of Anatolian provinces formerly belonging to the eastern Roman Empire. It had successfully withstood waves of European crusading ventures while capitalizing on the further misfortunes of Byzantium, taking over several key ports on the Mediterranean and the Black Sea as well as cultivating a flourishing overland trade.

But in 1243, the Seljuks of Rûm were forced to surrender to the Mongols, who had already succeeded in occupying what is now Iraq, Iran, portions of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the Christian kingdoms of Georgia and Armenia. Thereafter, the Mongols easily found their way into regions weakened by centuries of Islamic infighting and Christian crusading movements. The eastern Roman Empire had been fatally weakened by the Fourth Crusade. Constantinople was now controlled by the Venetians, and Byzantine successor states centered on Nicaea (in Anatolia) and Epirus (in northern Greece) were hanging on by their fingertips. The capitulation of Rûm left remaining Byzantine possessions in Anatolia without a buffer zone, and most of these were absorbed by the Mongols.

In 1261, emperor Michael VIII Paleologus (r. 1259–1282) managed to regain control of Constantinople and its immediate hinterland, but the depleted empire he ruled was ringed by hostile neighbors. The crusader principality of Antioch, which had been founded in 1098, finally succumbed to the Mongols in 1268. The Mongols themselves were halted in their drive toward Palestine only by the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, established in 1250 and ruled by a powerful military caste of non-Arab Muslims. The name of this dynasty reflects the fact that its founders were originally Turkic slaves (in Arabic, mamlūk means “an enslaved person”).

All of these disparate territories came to be called the Ilkhanate, the “subordinate khanate,” meaning that its Mongol rulers paid deference to the Great Khan. The first Ilkhan was Hulagu, a brother of China’s Kublai Khan. His descendants would rule this realm for another eighty years, eventually converting to Islam but remaining hostile toward the Mamluk Muslims, who were their chief rivals.

The Pax Mongolica and Its Price

Although the Mongols’ expansion of power into Europe had been checked, their combined conquests made them masters of lands that stretched from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean: one-fifth of the earth’s surface, the largest land empire in history. Yet no single Mongol ruler’s power was absolute within this domain. Kublai Khan (1260–1294), who took the additional title khagan (or “Great Khan”), never claimed to rule all the Mongol khanates directly. In his own domain of China and Mongolia, his power was highly centralized and built on the intricate (and ancient) imperial bureaucracy of China; but elsewhere, Mongol governance was directed at securing a steady tribute payment from subjugated peoples, which meant that local rulers could retain much of their power.

This distribution of authority made Mongol rule flexible and adaptable to local conditions, and in this it resembled the Persian Empire and also could be regarded as building on Hellenistic and Roman examples. But if their empire resembled those of antiquity in some respects, the Mongol khans differed from most contemporary European rulers in that they were highly tolerant of all religious beliefs. This was an advantage in governing peoples who observed an array of Buddhist, Christian, and Islamic practices, not to mention Hindus, Jews, and the many itinerant groups and individuals whose languages and beliefs reflected a melding of many cultures.

This acceptance of cultural and religious difference, alongside the Mongols’ encouragement of trade and love of rich things, created ideal conditions for some merchants and artists. Hence, the term Pax Mongolica (“Mongol Peace”) is often used to describe the century from 1250 to 1350, a period in many ways analogous to the one fostered by the Roman Empire at its greatest extent. No such term should be taken at face value, however, because this peace was bought at a great price. The artists whose varied talents created the gorgeous textiles, utensils, and illuminated books prized by the Mongols were not all willing participants in a process that was usually disruptive and often violent. Many were captives subject to ruthless relocation. The Mongols would often transfer entire families and communities of craftsmen from one part of the empire to another, directly and indirectly encouraging a fantastic blend of artistic techniques, materials, and motifs. The result was an intensive period of cultural exchange that might combine Chinese, Persian, Venetian, and Hungarian influences (among many others) in a single work of art. These objects encapsulate the many legacies of the Mongols’ empire.

The Mongol Peace was also achieved at the expense of many flourishing Muslim cities that were devastated or crippled during the bloody process of Mongol expansion—cities that had preserved the heritage of even older civilizations. The city of Heràt, situated in one of Afghanistan’s few fertile valleys and described by the Persian poet Rumi as the “pearl in the oyster,” was entirely destroyed by Genghis Khan in 1221 and did not fully recover for centuries. Baghdad, the splendid capital of the Abbasid caliphate and a haven for artists and intellectuals since the eighth century, was savagely besieged and sacked by the Mongols in 1258. Amid many other atrocities, the capture of the city resulted in the destruction of the House of Wisdom, the library and research center where Muslim scientists, philosophers, and translators preserved classical knowledge and advanced cutting-edge scholarship in such fields as mathematics, engineering, and medicine.

Baghdad’s destruction marked the end of medieval Islam’s golden age, since the establishment of the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia eradicated a continuous zone of Islamic influence that had blended cultures stretching from southern Spain and North Africa to India.

Bridging East and West

To facilitate the movement of people and goods within their empire, the Mongols began to control the caravan routes that led from the Mediterranean and the Black Sea through central Asia and into China, policing bandits and making conditions safer for travelers. They also encouraged and streamlined trade by funneling many exchanges through the Persian city of Tabriz, on which both land and sea routes from China converged. These measures accelerated and intensified the possible contacts between the Far East and the West. Prior to Mongol control, such commercial networks had been inaccessible to most European merchants. The Silk Road was not so much a highway as a tangle of trails and trading posts, with few outsiders who understood its workings. Now travelers at both ends of the route found their way smoothed.

Competing Viewpoints

Two Travel Accounts

Two of the books that influenced Christopher Columbus and his contemporaries were travel narratives describing the exotic worlds that lay beyond Europe—worlds that may or may not have existed as they are described. The first excerpt here is taken from the account dictated by Marco Polo of Venice in 1298. The young Marco had traveled overland from Constantinople to the court of Kublai Khan in the early 1270s, together with his father and uncle. He became a gifted linguist and remained at the Mongol court until the early 1290s, when he returned to Europe after a journey through Southeast Asia and Indonesia, and across the Indian Ocean. The second excerpt is from the Book of Marvels, attributed to John de Mandeville. This is an almost entirely fictional account of wonders that also became a source for European ideas about Southeast Asia. This particular passage concerns a legendary Christian figure named Prester (“Priest”) John, who is alleged to have traveled to the East and become a great ruler.

Marco Polo’s Description of Java

Now know that when one leaves Champa1 and went between south and southeast 1,500 miles, then one comes up to a very large island called Java which, according to what good sailors say who know it well, is the largest island in the world, for it is more than three thousand miles around. It has a great king; they are idolators and pay tribute to no man in the world. This island is one of very great wealth: they have pepper, nutmeg, spikenard, galangal, cubeb, cloves, and all the expensive spices you can find in the world. To this island come great numbers of ships and merchants who buy many commodities and make great profit and great gain there. On this island, there is such great treasure that no man in the world could recount or describe it. I tell you the Great Khan could never have it on account of the long and fearsome way in sailing there. Merchants from Zaytun2 and Mangi3 have already extracted very great treasure from this island, and continue to do so today.

Source: Marco Polo, Here the Great Island of Java is Described, trans. Sharon Kinoshita (Indianapolis/Cambridge, 2016), p. 149.

John de Mandeville’s Description of Prester John

This emperor Prester John has great lands and has many noble cities and good towns in his realm and many great, large islands. For all the country of India is separated into islands by the great floods that come from Paradise, that divide the land into many parts. And also in the sea he has many islands. . . .

This Prester John has under him many kings and many islands and many varied people of various conditions. And this land is full good and rich, but not so rich as is the land of the Great Khan. For the merchants do not come there so commonly to buy merchandise as they do in the land of the Great Khan, for it is too far to travel to. . . .

[Mandeville then goes on to describe the difficulties of reaching Prester John’s lands by sea.]

This emperor Prester John always takes as his wife the daughter of the Great Khan, and the Great Khan in the same way takes to wife the daughter of Prester John. For these two are the greatest lords under the heavens.

In the land of Prester John there are many diverse things, and many precious stones so great and so large that men make them into vessels such as platters, dishes, and cups. And there are many other marvels there that it would be too cumbrous and too long to put into the writing of books. But of the principal islands and of his estate and of his law I shall tell you some part.

This emperor Prester John is Christian and a great part of his country is Christian also, although they do not hold to all the articles of our faith as we do. . . .

And he has under him 72 provinces, and in every province there is a king. And these kings have kings under them, and all are tributaries to Prester John.

And he has in his lordships many great marvels. For in his country is the sea that men call the Gravelly Sea, that is all gravel and sand without any drop of water. And it ebbs and flows in great waves as other seas do, and it is never still. . . . And a three-day journey from that sea there are great mountains out of which flows a great flood that comes out of Paradise. And it is full of precious stones without any drop of water. . . .

He dwells usually in the city of Susa [in Persia]. And there is his principal palace, which is so rich and so noble that no one will believe the report unless he has seen it. And above the chief tower of the palace there are two round pommels of gold and in each of them are two great, large rubies that shine full brightly upon the night. And the principal gates of his palace are of a precious stone that men call sardonyxes [a type of onyx], and the frames and the bars are made of ivory. And the windows of the halls and chambers are of crystal. And the tables upon which men eat, some are made of emeralds, some of amethyst, and some of gold full of precious stones. And the legs that hold up the tables are made of the same precious stones. . . .

Source: Mandeville’s Travels, ed. M. C. Seymour (Oxford: 1967), pp. 195–99 (language modernized from Middle English by R. C. Stacey).

Questions for Analysis

- What does Marco Polo want his readers to know about Java, and why? What does this suggest about the interests of these intended readers?

- What does Mandeville want his readers to know about Prester John and his domains? Why are these details so important?

- Which of these accounts seems more trustworthy, and why? Even if we cannot accept one or both at face value, what insight do they give us into the expectations of Columbus and the other European adventurers who relied on these accounts?

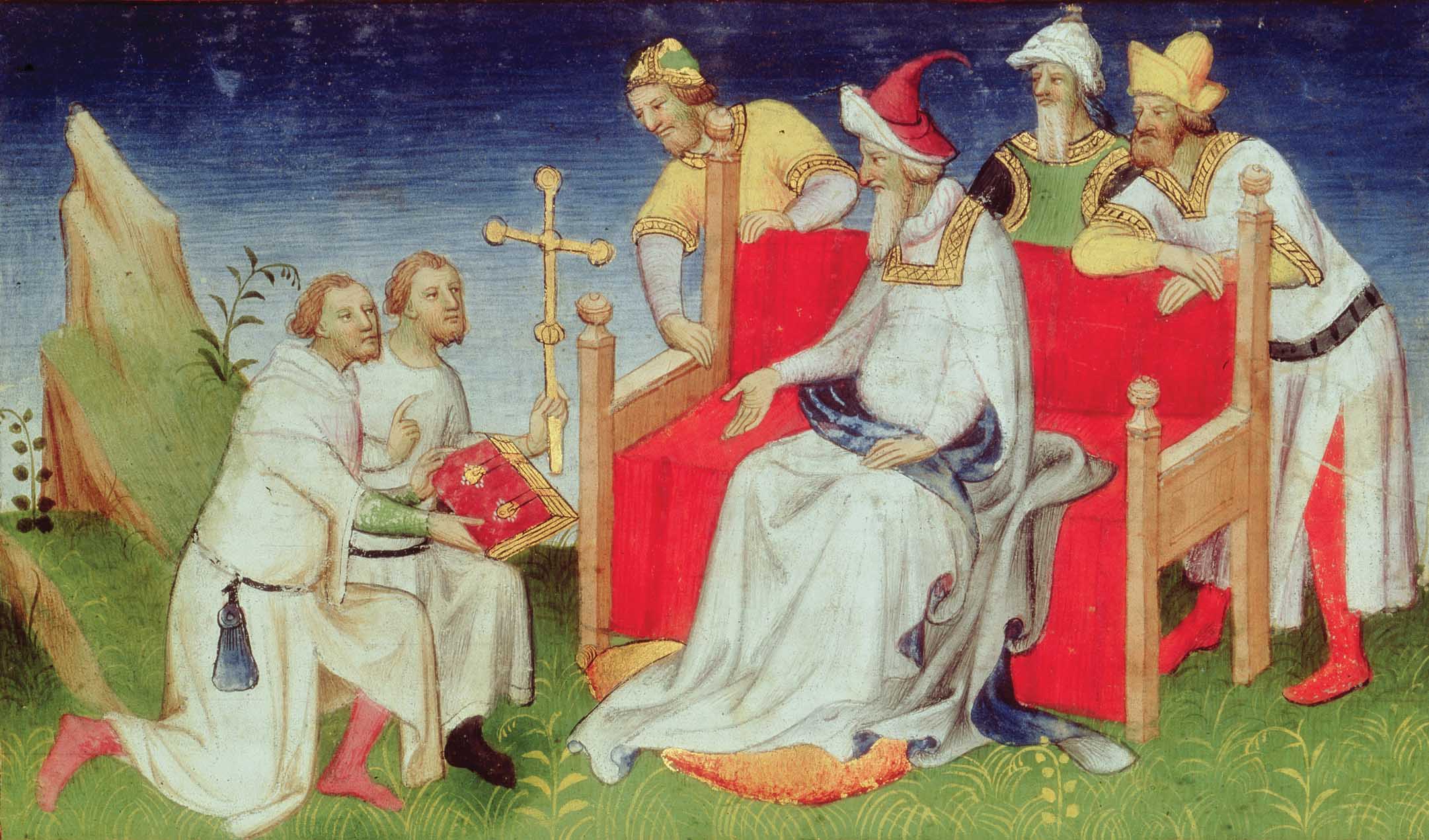

Among the first travelers from the West were Franciscan missionaries whose journeys were bankrolled by European rulers. In 1253, the friar William of Rubruck was sent by King Louis IX of France as his ambassador to the Mongol court, with letters of introduction and instructions to make a full report of his findings. Merchants quickly followed. The most famous are three Venetians: the brothers Niccolò and Matteo Polo, and Niccolò’s son, Marco (1254–1324). Marco Polo’s account of his travels (which began when he was seventeen) includes a report of his twenty-year sojourn in the service of Kublai Khan, and the story of his journey home through the Spice Islands, India, and Persia (see Competing Viewpoints above). As we noted on page 3, this book had an enormous effect on the European imagination; Christopher Columbus’s copy still survives.

Even more impressive in scope than Marco’s travels are those of the Muslim adventurer Ibn Battuta (1304–1368), who left his native Morocco in 1326 to go on the sacred pilgrimage to Mecca—but then kept going. By the time he returned home in 1354, he had been to China and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as to the ends of both the Islamic and Mongolian worlds: a journey of over 75,000 miles.

The window of opportunity that made such journeys possible was relatively narrow, however. By the middle of the fourteenth century, hostilities among and within various components of the Mongol Empire were making travel along the Silk Road perilous. The Mongols of the Ilkhanate, who dominated the ancient trade routes that ran through Persia, came into conflict with the Italian merchants from Genoa, who controlled trade at the western ends of the Silk Road, especially in the transport depot of Tabriz. Mounting pressures finally forced the Genoese to abandon Tabriz, thereby breaking one of the major links in the commercial chain forged by the Mongol Peace. Then, in 1346, the Mongols of the Golden Horde besieged the Genoese colony at Caffa on the Black Sea. This event simultaneously disrupted trade while becoming a conduit for the transmission of the Black Death, whose reemergence and spread within Asia had been facilitated by these interconnected networks and by the Mongol conquests (see page 33).

Over the next few decades, the medieval economy would struggle to overcome the devastating effects of the massive depopulation caused by the plague, which made recovery from these setbacks slower and harder. In the meantime, in 1368, the last Mongol rulers of China were overthrown, and most foreigners were now denied access to its borders; the remaining Mongol warriors were restricted to cavalry service in the imperial armies of the new Ming dynasty. The conditions that had fostered an integrated trans-Eurasian cultural and commercial network were no longer sustainable. Yet the view of the world that had been fostered by Mongol rule continued to exercise a lasting influence. European memories of the Far East would be preserved and embroidered, and the dream of reestablishing close connections between Europe and China would survive to influence a new round of commercial and imperial expansion in the centuries to come.

Endnotes

- A collective name for the kingdoms of central Vietnam. Return to reference 1

- The major port city of Quanzhou on southeastern coast of China. Return to reference 2

- The kingdom of the Southern Song in China, south of the Huai River. The word mangi (or manzi) means “barbarians,” which is what the northern Chinese called the people of the southern realm. When Marco Polo was in the service of the Great Khan, the Mongol conquest of the kingdom was still ongoing. It was completed in 1279. Return to reference 3

Glossary

- Genghis Khan

- (c. 1167–1227) “Oceanic Ruler,” the title adopted by the Mongol chieftain Temujin, founder of a dynasty that conquered much of southern Asia.

- Pax Mongolica

- In imitation of the Pax Romana (“The Roman Peace”), this is the phrase used to describe the relatively peaceful century after the Mongol conquests, which enabled an intensified period of trade, travel, and communication within the Eurasian landmass.

- Marco Polo

- (1254–1324) Venetian merchant who traveled throughout Asia for twenty years and published his observations in a widely read memoir.