![]() Pastoral Nomads

Pastoral Nomads

CLIMATE CHANGE, NOMADIC MOVEMENT, AND THE EMERGENCE OF TERRITORIAL STATES

At the end of the third millennium BCE, a changing climate, drought, and food shortages led to the overthrow of ruling elites throughout much of Afro-Eurasia. Walled cities could not defend their hinterlands. Trade routes lay open to predators, and pillaging became a lucrative enterprise. From the relatively sparsely populated and isolated Inner Eurasian steppes, clans of pastoral nomads (pastoralists who move with their herds in perpetual motion across large areas, like the steppe lands of Inner Eurasia, and facilitate long-distance trade) swept across vast distances, eventually threatening settled people in cities.

More immediately threatening were those herders living in close proximity to settled agriculturalists, namely transhumant herders (pastoralists who move seasonally from lowlands to highlands, in proximity to city-states, with which they trade the products of their flocks, including milk, fur, and hides, for urban products such as manufactured goods, including metals like bronze). From the borderlands of the Iranian plateau and the Arabian Desert, these herders advanced into the populated areas, searching for food and resources. Similar migrations occurred in the Indus River valley and the Yellow River valley. (See Map 3.1.)

Many transhumant herders and pastoral nomads settled in the agrarian heartlands of Mesopotamia, the Indus River valley, the highlands of Anatolia, Iran, China, and Europe. After the first wave of newcomers, more migrants arrived by foot or in wagons pulled by draft animals. Some sought temporary work; others settled permanently. This millennia-long process is sometimes referred to as the Indo-European migrations (migrations, tracked linguistically and culturally, of the peoples of a distinct language group, including Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, and German, from central Eurasian steppe lands into Europe, Southwest Asia, and South Asia). (See Analyzing Global Developments: How Languages Spread: The Case of Nomadic Indo-European Languages.)

Environmental changes compelled humans across Afro-Eurasia to adapt or perish. When and where the pastoral nomads and transhumant herders managed to adjust to the dry conditions, they prompted the rise of new, larger, and expansionist territorial states, from pharaonic Egypt and Mesopotamia to Vedic South Asia and Zhou China. Using chariots, the horse-mounted nomads introduced technologies that led to new forms of warfare, whose spread transformed the Afro-Eurasian world. Moreover, the new rulers’ innovations in state building and governance enabled people to rebuild their communities and to flourish in the changed climate.

Climate Change and Migrations

Desperate for secure water sources and pastures, many transhumant herders and pastoralists migrated onto the highland plateaus bordering the inner Eurasian steppes. From there, some continued into the more populated river valleys and soon were competing with the farming communities over space and resources. They also streamed in from the western and southern deserts in Southwest Asia in modern-day inner Syria and Arabia. These migrants brought horses and new technologies that were useful in warfare. They brought new languages and religious practices but also created new pressures to feed, house, and clothe an ever-growing population.

HORSES AND CHARIOTS Although the hard-riding pastoral nomads contributed much to settled societies (they linked cities in South Asia and China for the first time, enhanced trade, and maintained peace), they could not control what the elites whom they disrupted wrote about them. Those who lost power described the nomadic warriors as “barbaric,” portraying them as cruel enemies of “civilization.” Yet what we know of these nomads today suggests that they were anything but barbaric.

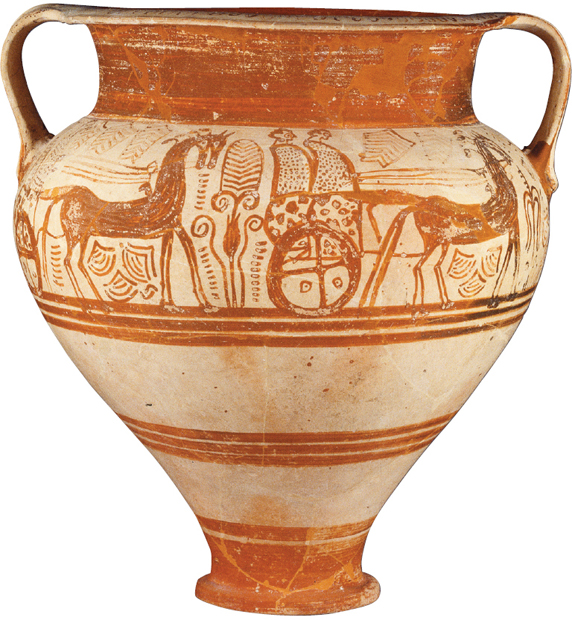

Perhaps the most vital breakthroughs that nomadic pastoralists transmitted to settled societies were the harnessing of horses and the invention of chariots (horse-drawn vehicles with two spoked and metal-rimmed wheels, which not only were used for processions and races but also revolutionized warfare in the second millennium BCE). The chariot revolution was made possible, however, only through the interactions of pastoralists and settled communities. On the vast steppe lands north of the Caucasus Mountains, during the late fourth millennium BCE, settled people had domesticated horses in their native habitat. The domestication of horses was a major breakthrough for humans. Horses could forage for themselves, even in snow-covered lands; hence they did not require humans to find food for them. Moreover, they could be ridden up to 30 miles a day. Elsewhere, as on the northern steppes of what is now Russia, horses were a food source. Only during the late third millennium BCE did people harness them with cheek pieces and mouth bits, signaling their use for transportation. Parts of the horse harnesses, made from wood, bronze, and iron and found in tombs scattered across the steppe, have revealed the evolution of headgear from simple mouth bits to full bridles with headpiece, mouthpiece, and reins.

THE GLOBAL VIEW

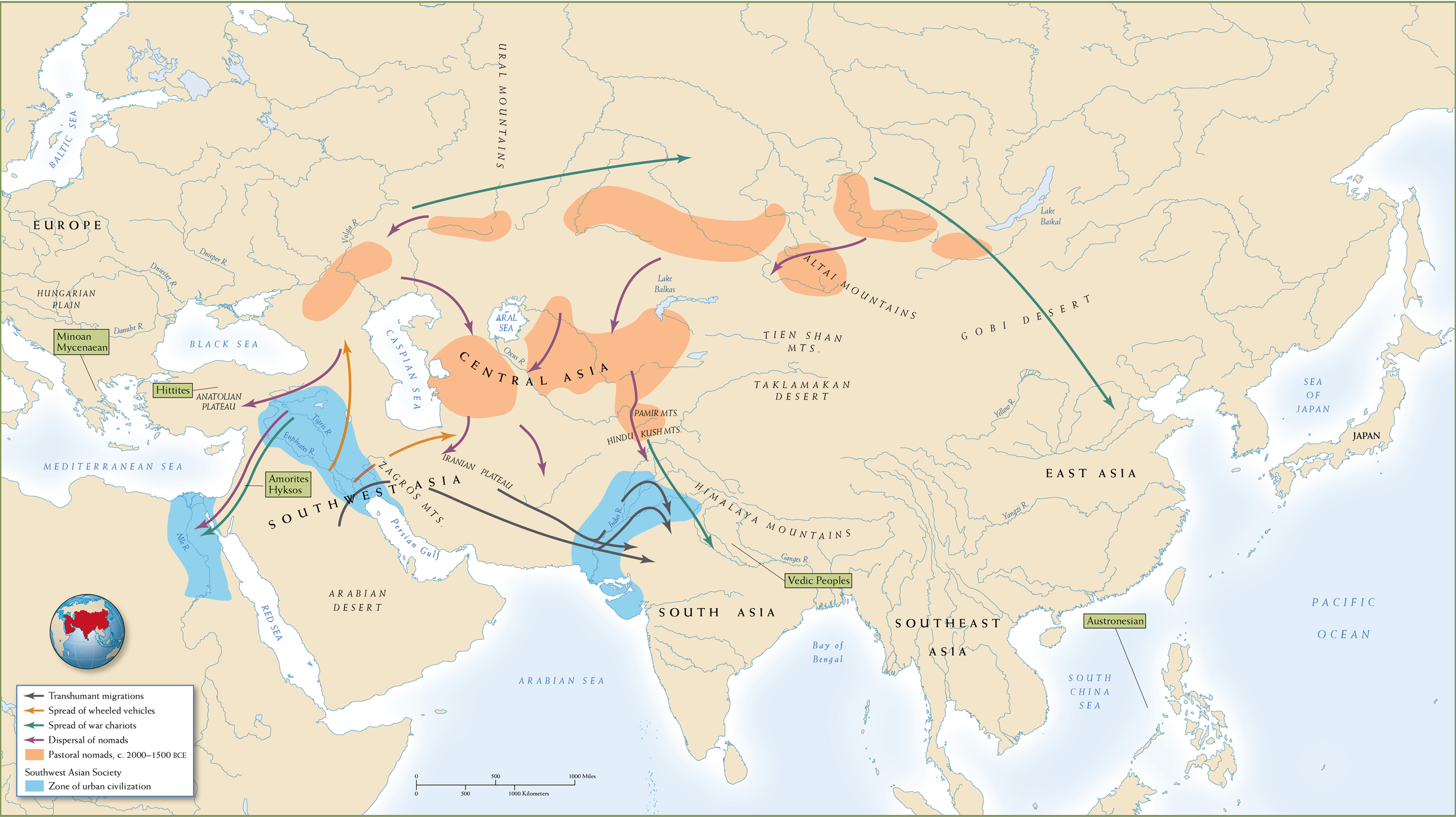

MAP 3.1 | Nomadic Migrations in Afro-Eurasia, 2000–1000 BCE

Many different groups of nomadic peoples were on the move in the second millennium BCE, migrating into many of the regions that had hosted the river-basin-fueled, city-state-filled cultures of the third millennium BCE.

- According to this map, from what specific parts of the world did pastoral peoples migrate? Into what specific areas did they move? What geographical features may have shaped the migrations in terms of the regions left behind, the routes traveled, and the locations traveled to?

- What regions did these migrations bring into closer connection?

- What technological innovations were spread by these migrations, and across what regions did that technology spread?

ANALYZING GLOBAL DEVELOPMENTS

How Languages Spread: The Case of Nomadic Indo-European Languages

Linguistics, or the study of language, is an important tool in world history. Language arose independently in a number of places around the world. All languages change with time, and their divergence from a mother tongue serves as a tool in determining at what point different languages, like German or French, separated from one another. Scholars call related tongues with a common origin “language families.” Even though members of the same language family diverged over time, they all share grammatical features and root vocabularies.

Although there are more than 100 language families, a much smaller number have influenced vast geographical areas. For example, the Altaic languages spread from central Asia to Europe. The Sino-Tibetan language family includes Mandarin, the most widely spoken language in the world. The Uralic family, which includes Hungarian and Finnish, occurs mainly in Europe. The Afro-Asiatic language family contains several hundred languages spoken in North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southwest Asia, Semitic languages such as Hebrew and Arabic among them.

One language family that linguists have studied extensively, and the one with the largest number of speakers today, is Indo-European. It was identified by scholars who recognized similarities in grammar and vocabulary among classical Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, and Latin. Living languages in this family include English, Irish, German, Norwegian, Portuguese, French, Russian, Persian, Hindi, and Bengali. For the past 200 years, comparative linguists have sought to reconstruct Proto-Indo-European, the parent of all the languages in the family. They have drawn conclusions about its grammar, hypothesizing a highly inflected language with different endings on nouns and verbs according to their use. They have also made suggestions about its vocabulary. For example, after analyzing patterns of linguistic change, scholars have proposed that the basic Indo-European root that means “horse”—in Sanskrit, a´sva; Persian, aspa; Latin, equus; and Greek, hippos (íppob)—is *ekwo-.

Table 3.1 demonstrates the similarity of words in some of the major Indo-European languages. We have emphasized numbers, which are especially stable in language systems because people do not like to change the way they count. We have also provided the equivalents in two Semitic languages (Arabic and Hebrew) to show how different these basic words are in another language family (the Afro-Asiatic).

Attempts to locate the homeland of the original speakers of Proto-Indo-European involve mapping the reconstructed vocabulary onto a matching geography. For example, some of the vocabulary contains words for “snow,” “mountain,” and “swift river,” as well as for animals that are not native to Europe, such as “lion,” “monkey,” and “elephant.” Other words describe agricultural practices and farming tools that date back as far as 5000 BCE. Many linguists believe that nomadic and pastoral peoples of the Eurasian steppes took this language—along with their precious horses and chariots—as far as the borderlands of what is now Afghanistan and eastern Iran.

Migration is only one of the possible reasons that languages move and change over vast areas and periods of time. Other influential factors are invasions, climatic conditions, natural resources, and ways of life.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What relationships does Table 3.1 suggest between the Semitic languages and the Indo-European languages?

- How does the study of linguistics enhance our understanding of human geography?

|

TABLE 3.1 | Similarity of Words in Some Major Indo-European Languages |

||||||||

|

WORDS OF COMMON ORIGIN IN INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES |

SEMITIC LANGUAGES |

|||||||

|

SANSKRIT |

HINDI |

GREEK |

LATIN |

FRENCH |

GERMAN |

ARABIC |

HEBREW |

|

|

Numbers |

||||||||

|

one |

eka |

ek |

hen |

unus |

un |

ein |

wahid |

ehad |

|

two |

dva |

do |

duo |

duo |

deux |

zwei |

ithnin |

shnayim |

|

three |

tri |

teen |

treis |

tres |

trois |

drei |

thalatha |

shlasha |

|

four |

catur |

chār |

tessara |

quattuor |

quatre |

vier |

arba´a |

arba´a |

|

five |

pañca |

pānch |

penta |

quinque |

cinq |

fünf |

khamsa |

hamisha |

|

ten |

daśa |

das |

deka |

decem |

dix |

zehn |

ashra |

asara |

|

hundred |

śata |

sau |

hekaton |

centum |

cent |

hundert |

mi´a |

me´a |

|

Other common words |

||||||||

|

father |

pitŗ |

pitā |

pater |

pater |

père |

vater |

abu |

Aba |

|

mother |

mātŗ |

mātā |

mêter |

mater |

mère |

mutter |

umm |

em |

|

son |

sūnu |

betā |

huios |

filius |

fils |

sohn |

ibn |

ben |

|

heart |

hŗdaya |

dil |

kardia |

cor |

coeur |

herz |

qalb |

lev |

|

foot |

pada |

pair |

pous |

pes |

pied |

fuss |

qadam |

regel |

|

god |

deva |

dev |

theos |

deus |

dieu |

gott |

Allah |

yahweh |

Sometime around 2000 BCE, pastoral nomads in the mountains of the Caucasus joined the harnessed horse to the chariot. The invention of the chariot yoked to agile, speedy, and highly trained horses transformed warfare. Pastoralists lightened chariots so their warhorses could pull them faster. They were so light that an empty one could be lifted by one hand. The chariots had spoked wheels made of special wood and bent into circular shapes, as well as wheel covers, axles, and bearings (all produced by settled people), and durable metal went into the chariots’ moving parts. Hooped bronze and, later, iron rims reinforced the spoked wheels. Initially iron was a decorative and experimental metal, and all tools and weapons were bronze. Iron’s hardness and flexibility, however, eventually made it more desirable for reinforcing moving parts and protecting wheels, like those on the chariot. Thus, the horse-drawn chariots combined innovations by both nomads and settled agriculturalists.

These innovations—combining engineering skills, metallurgy, and animal domestication—and their ultimate diffusion revolutionized the way humans made war. The horse chariot slashed travel time between capitals and overturned the machinery of war. Slow-moving infantry now ceded to battalions of chariots. Each vehicle carried a driver and an archer and charged into battle with lethal precision and ravaging speed. In fact, the mobility, accuracy, and shooting power of warriors in horse-drawn chariots tilted the political balance, for after the nomads perfected this type of warfare (by 1600 BCE), they challenged the political systems of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Soon their innovations became central to the armies of Egypt, Assyria, Persia, the Vedic kings of South Asia, and the Zhou rulers in China, as well as to local nobles as far west as Italy, Gaul, and Spain. Only with the arrival of cheaper armor made of iron (after 1000 BCE) could foot soldiers (in China, armed with crossbows) recover their military importance. And only after states developed cavalry units of horse-mounted warriors did chariots lose their decisive military advantage. For much of the second millennium BCE, then, charioteer elites prevailed in Afro-Eurasia.

For city dwellers in the river basins, the first sight of horse-drawn chariots must have been terrifying, but they knew that war making had changed and they scrambled to adapt. The pharaohs in Egypt copied chariots from their Hyksos invaders, and they came to value the vehicles highly. For example, the young pharaoh Tutankhamun (r. c. 1336–1327 BCE) was a chariot archer who made sure that his war vehicle and other gear accompanied him in his tomb. A century later, the Shang rulers of the Yellow River valley, in the heartland of agricultural China, likewise were entombed with their horse chariots.

The Emergence of Territorial States

Nomad and transhumant populations toppled the river-basin cities in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China. The turmoil that ensued sowed the seeds for a new type of regime: the territorial state. Sargon and the Akkadians had set up a short-lived territorial state in earlier Mesopotamia (2334–2200 BCE) (see Chapter 2), but the martial innovations and political and environmental crises of the early second millennium BCE helped spur more enduring development of territorial states elsewhere. A territorial state was a centralized kingdom organized around a charismatic ruler. The new rulers of these territorial states exerted power not only over localized city-states but also over distant hinterlands. They enhanced their stability through rituals for passing the torch of command from one generation to the next. People no longer identified themselves as residents of cities; instead, they felt allegiance to large territories, rulers, and broad linguistic and ethnic communities. These territories for the first time had identifiable borders, and their residents felt a shared identity. Territorial states differed from the city-states that preceded them in that the new territorial states in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China based their authority on monarchs, widespread bureaucracies, elaborate legal codes, large territorial expanses, definable borders, and ambitions for continuous expansion.

Glossary

- pastoral nomads

- Peoples who move with their herds in perpetual motion across large areas, like the steppe lands of Inner Eurasia, and facilitate long-distance trade.

- transhumant herders

- Pastoral peoples who move seasonally from lowlands to highlands in proximity to city-states, with which they trade the products of their flocks (milk, fur, hides) for urban products (manufactured goods, such as metals).

- Indo-European migrations

- The migrations, tracked linguistically and culturally, of the peoples of a distinct language group (including Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, and German) from central Eurasian steppe lands into Europe, Southwest Asia, and South Asia.

- chariots

- Horse-drawn vehicle with two spoked and metal-rimmed wheels. Made possible by the interaction of pastoralists and settled communities, the chariot revolutionized warfare in the second millennium BCE.

- territorial state

- A kingdom made up of city-states and hinterlands joined together by a shared identity, controlled through the centralized rule of a charismatic leader, and supported by a large bureaucracy, legal codes, and military expansion.