SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Explain how magnification improves resolution of a microscopic image.

- Explain what can be learned from different kinds of microscopy.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

CASE HISTORY 3.1

Bacteria Invade the Brain

An illustration showing a lateral view of the complete human brain. The brain consists of a larger domed component, the cerebrum, connected to a smaller inferior component, the cerebellum, and to the brain stem. The brain is light pink in this illustration. Its surface is covered with deep, winding wrinkles.

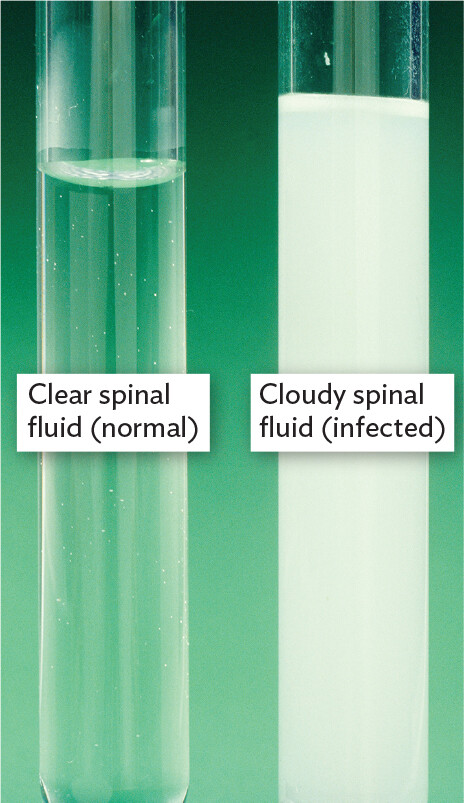

Eleanor presented in the urgent-care facility with headache, fever, and neck stiffness. She told the clinician that light hurt her eyes, and she had difficulty bending her head forward. On examination, her temperature was 38°C (100.8°F) and her blood pressure was low, making her feel dizzy when she stood up. Eleanor underwent a lumbar puncture, or spinal tap, a procedure in which a spinal needle is inserted between the lumbar vertebrae to withdraw a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This fluid bathes the meningeal lining of the brain. Normal CSF is clear and sterile, free of cells, but Eleanor’s CSF sample was cloudy. The cloudy fluid was indicative of bacterial meningitis.

Bacterial meningitis is the swelling of tissues around the brain and spinal cord caused by bacterial infection. Meningitis develops rapidly, and some strains of pathogen confer a 40% fatality rate. Thus, rapid diagnosis is critical. Fortunately, Eleanor received a prompt diagnosis and antibiotic therapy. Her partner also received antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis (prevention). Eleanor asked about her co-workers. The clinician assured her that friends and co-workers who do not share intimate contact are not at risk for transmission.

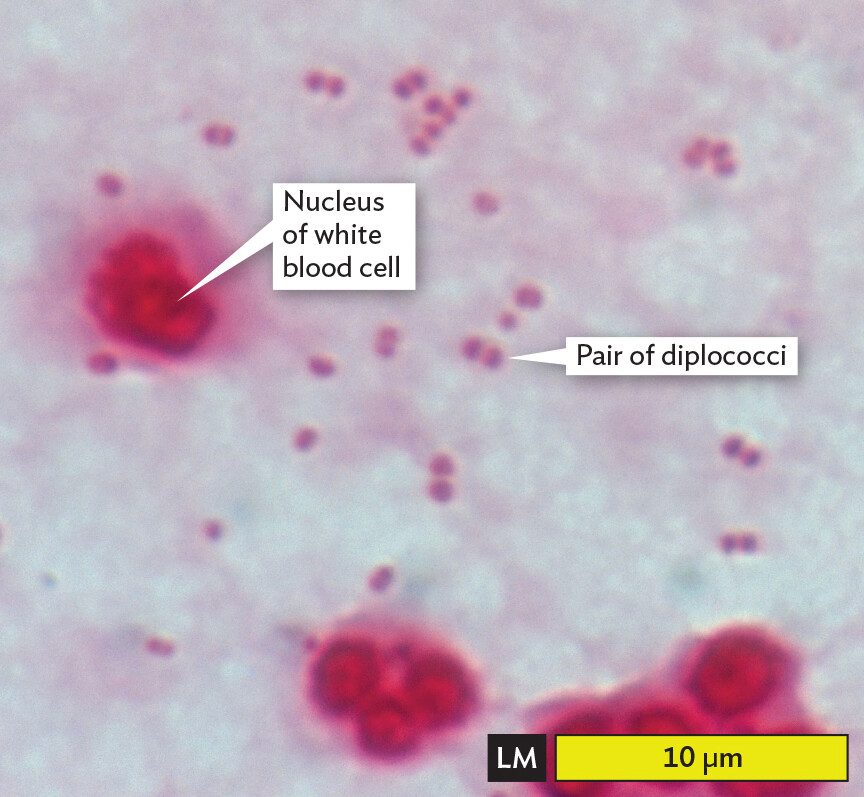

In Case History 3.1 (Figure 3.1A), what was in the cloudy CSF? Cerebrospinal fluid normally is clear and sterile, but Eleanor’s sample was full of white blood cells (WBCs). The cells scattered light, resulting in a cloudy appearance. The WBCs were responding to a bacterial infection (to be presented in Chapter 15). Microscopy revealed the individual WBCs, along with the much smaller cells of bacteria (Figure 3.1B). The bacteria have a shape called diplococcus (paired spherical cells), consistent with the species Neisseria meningitidis. Both the WBC nuclei and the Neisseria bacteria appear pink when Gram-stained (see Section 3.4).

A photograph comparing normal and infected cerebrospinal fluid. There are two glass tubes. One tube contains normal spinal fluid, which is clear and has an appearance similar to water. The second tube contains infected spinal fluid, which is cloudy white and opaque.

A light micrograph of infected cerebrospinal fluid. The slide is Gram stained, producing a pink coloration to the contents. Several bright pink white blood cells and numerous dark pink diplococci bacteria are seen in an otherwise pale pink environment. The white blood cells are each roughly spherical. They range from 5 to 10 micrometers in diameter. They have distinct nuclei that vary slightly in structure. The diplococci bacteria each have a length of about 1 micrometer and a width of 0.5 micrometer.

Even before being viewed in a microscope, the WBCs and bacteria in Eleanor’s cerebrospinal fluid were detected in the tube as suspended particles causing a cloudy appearance. Detection means seeing that an object exists, even if you cannot see its details. For example, our eyes can detect a large group of microbes such as a spot of mold on a piece of bread (about a million cells).

Within the tube or the colony, the presence of cells may be detected, yet no individual cell can be resolved—that is, observed as a distinct entity separate from other cells. The cells cannot be resolved individually because they are too small.

In Case History 3.1, microscopy was needed to resolve the size and shape of the diplococcus bacteria, and their specific shape confirmed the diagnosis of N. meningitidis. Most microbial cells are “microscopic,” requiring the use of a microscope to be seen. In a microscope, magnification increases the apparent size of an image. “Useful magnification” enables resolution of smaller separations between objects and thus increases the information obtained by our eyes. Why do we need magnification to resolve individual microbes? What makes a cell too small for unaided eyes to see? Surprisingly, the answer depends on the observer. Our definition of “microscopic” is based not on inherent properties of the organism under study but on the properties of the human eye. What is “microscopic” actually lies in the eye of the beholder.

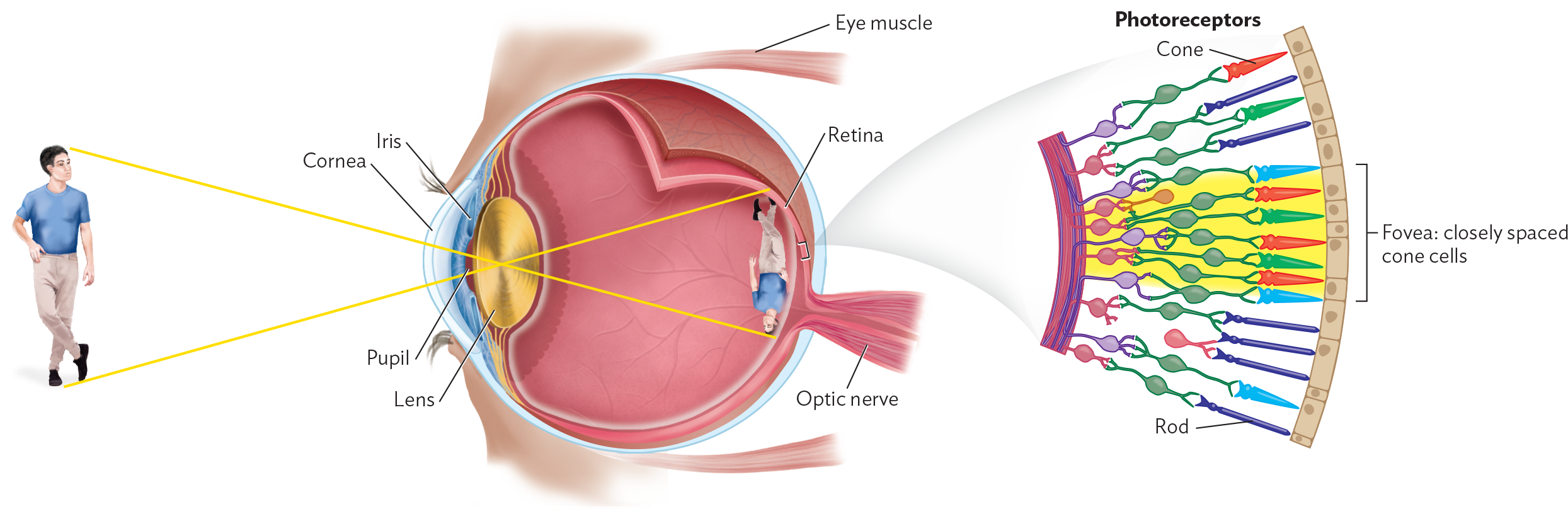

The size at which objects become visible depends on the resolution of the observer’s eye. Resolution is the smallest distance by which two objects can be separated and still be distinguished. In the eyes of humans and other animals, resolution is achieved by focusing an image on a retina packed with light-absorbing photoreceptor cells (rods and cones; Figure 3.2). A group of photoreceptors with their linked neurons forms one unit of detection, comparable to a pixel on a computer screen. The distance between two retinal “pixels” limits resolution.

A diagram explaining how structures in the human eye produce vision. The anterior aspect of the eye includes the pupil, surrounding iris, and overlying cornea. The cornea is a transparent dome. Eye muscles are located at the superior and inferior aspects of the eye. Immediately posterior to the pupil and iris is the lens, which is disc shaped. Images are reversed when they pass through the lens to reach the retina, which is located at the back of the eye. The optic nerve connects to the retina. A detailed view of the retina shows that it consists of a series of photoreceptors, which differ in shape. Some of these photoreceptors are cones and some are rods. Fovea refer to closely spaced cone cells in the retina. An illustration of a man is shown in front of the eye with the same illustration upside down in the back of the eye.

The resolution of the human retina (that is, the length of the smallest object most human eyes can see) is about 150m, or one-seventh of a millimeter. In the retina of an eagle, photoreceptors are more closely packed, so an eagle can resolve objects eight times as small or eight times as far away as a human can—hence the phrase “eagle-eyed,” meaning sharp-sighted.

Note: In this book, we use standard metric units for size:

Note: In this book, we use standard metric units for size:

1 millimeter (mm) = one-thousandth of a meter

=10−3m

1 micrometer (µm) = one-thousandth of a millimeter

=10−6m

1 nanometer (nm)= one-thousandth of a micrometer

=10−9m

1 picometer (pm)= one-thousandth of a nanometer

=10−12m

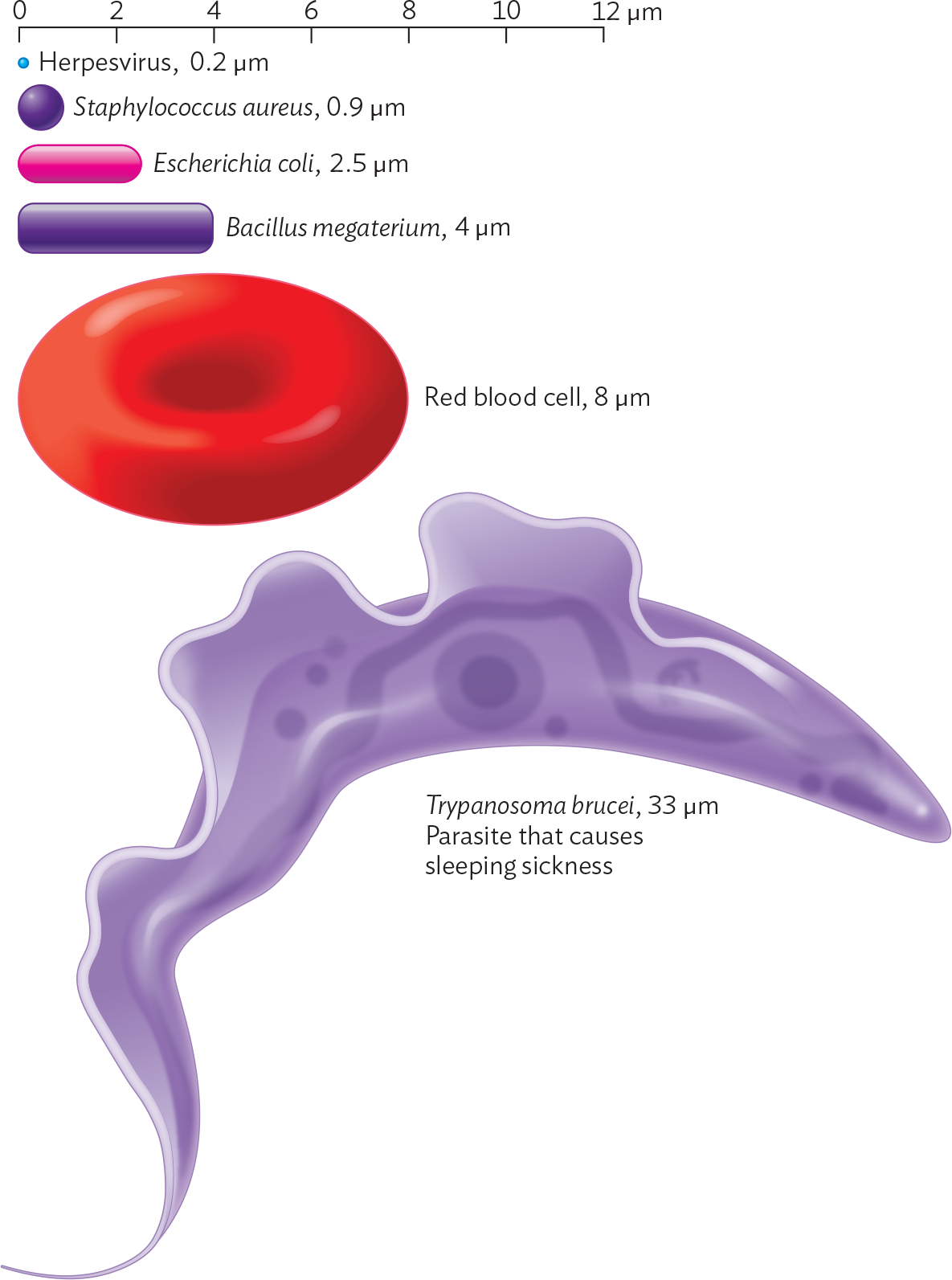

What is the actual size of a microbe? Different kinds of microbes differ in size, spanning several orders of magnitude, or powers of 10 (Figure 3.3). Eukaryotic microbes are often large enough that we can resolve their compartmentalized structure under a light microscope. An example is Trypanosoma brucei (33 µm), which causes sleeping sickness. This trypanosome has a nucleus and a whiplike flagellum. Prokaryotic microbes (bacteria and archaea) are generally smaller (0.4–10 µm); as a result, their overall shape can be seen under a light microscope, but their internal structures are too small to be resolved. Some eukaryotic microbes are as small as bacteria—for example, parasitic microsporidia are 1–40 µm—so the actual size range of eukaryotic microbes overlaps that of prokaryotes.

A diagram showing the relative sizes of different microbes and a red blood cell. There is a scale at the top spanning 0 to 12 micrometers. A series of microbes are arranged beneath the scale from smallest to largest. The smallest is the Herpesvirus, represented by a tiny sphere, which is 0.2 micrometer in diameter. Next is Staphylococcus aureus, represented by a small sphere, which is 0.9 micrometer in diameter. After is Escherichia coli, represented by a rounded rod, which is 2.5 micrometers in maximum dimension. Next is Bacillus megaterium, represented by a larger rod, which is 4 micrometers in maximum dimension. After is a red blood cell, represented by a biconcave disc, which is 8 micrometers in diameter. The largest in the series is Trypanosoma brucei, which is a parasite that causes sleeping sickness. It is 33 micrometers in length. The parasite consists of a tapered cylindrical structure with a fin like appendage protruding from one of the long sides of the cell.

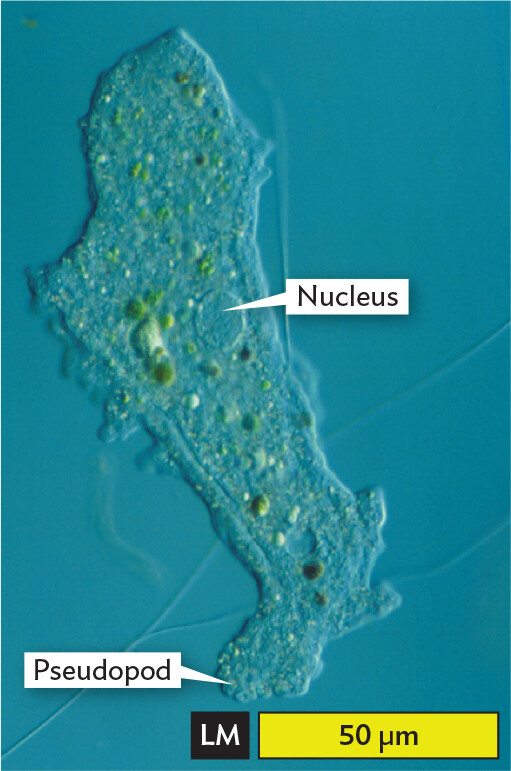

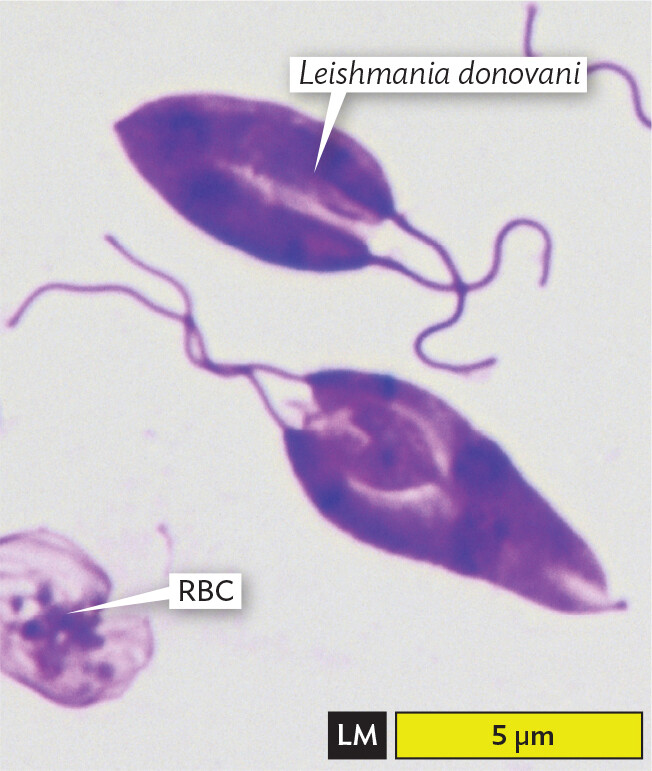

Eukaryotic microbial cells. Many eukaryotes, such as protozoa, can be resolved with light microscopy (LM) to reveal complex shapes and internal structures such as the nucleus. For example, the ameba in Figure 3.4A, from an aquatic ecosystem, has a large nucleus and a pseudopod that can engulf prey. Pseudopods can be seen to move by the streaming of their cytoplasm. A very different eukaryotic microbe is Leishmania donovani, a parasite of humans and animals, transmitted by sand flies. In Figure 3.4B, we see the parasite multiplying amid human red blood cells (RBCs). Parasite infections are discussed in Chapter 11.

A light micrograph of Amoeba proteus. The organism is irregularly shaped, spanning a length of about 125 micrometers and a width of about 40 micrometers. With no stain, the organism is transparent. Inside of the cell are numerous aggregates of green substance. A nucleus, which has the structure of a transparent sphere is identified. In one region of the cell, the membrane extends outward, forming a structure called a pseudopod.

A light micrograph of the parasite Leishmania donovani. There are two L donovani cells in the field of view. The cells are roughly teardrop shaped and are purple due to specialized staining. Two thin strands extend from the broader pole of each cell. Each cell is about 5 micrometers in length and up to 3 micrometers in width. A red blood cell, which has the shape of a biconcave disc, is located at the edge of the field of view.

The appearance of a microbe in an image depends on the type of microscopy. Table 3.1 shows the protozoan Giardia lamblia imaged by common types of microscopy. Giardia is an intestinal parasite that often contaminates water supplies and spreads in child-care centers. The cell has two nuclei and multiple flagella that generate a whiplike movement. But different kinds of microscopy show different aspects of the cell.

Examples of each type of microscopy are shown in Table 3.1.

Note: Each micrograph in this book has a label for the type of microscopy (black) with a scale bar (yellow). The length of the scale bar corresponds to the actual size magnified, such as 5 µm. Like a ruler, the scale bar applies to length measurements throughout the micrograph.

Note: Each micrograph in this book has a label for the type of microscopy (black) with a scale bar (yellow). The length of the scale bar corresponds to the actual size magnified, such as 5 µm. Like a ruler, the scale bar applies to length measurements throughout the micrograph.

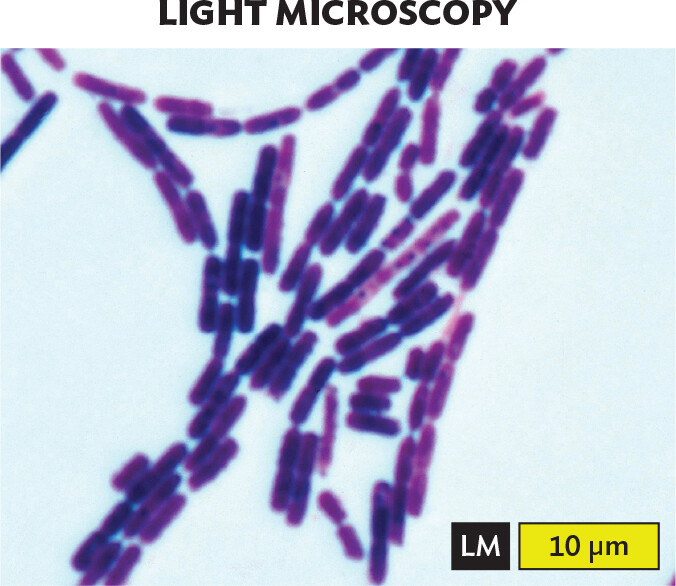

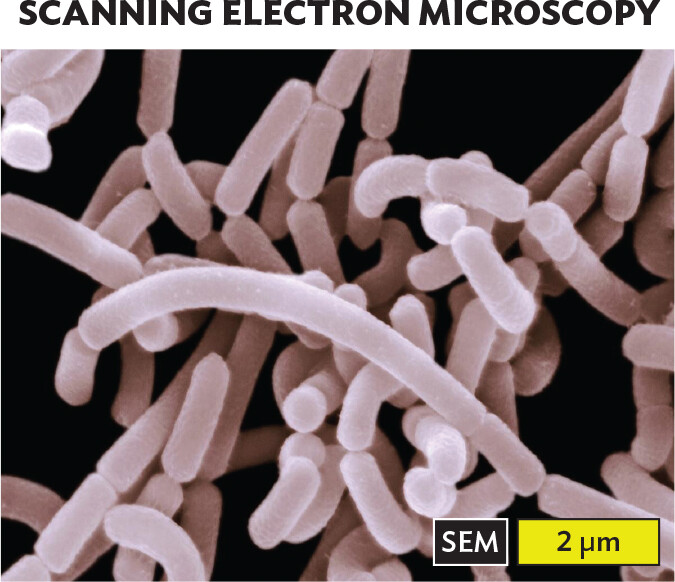

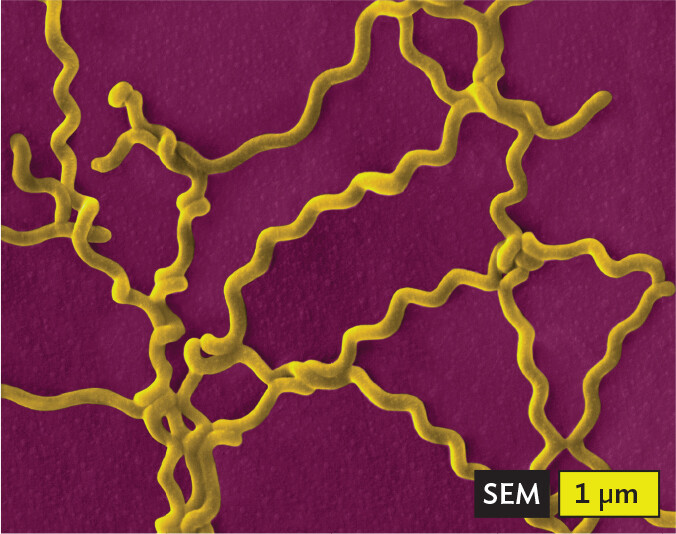

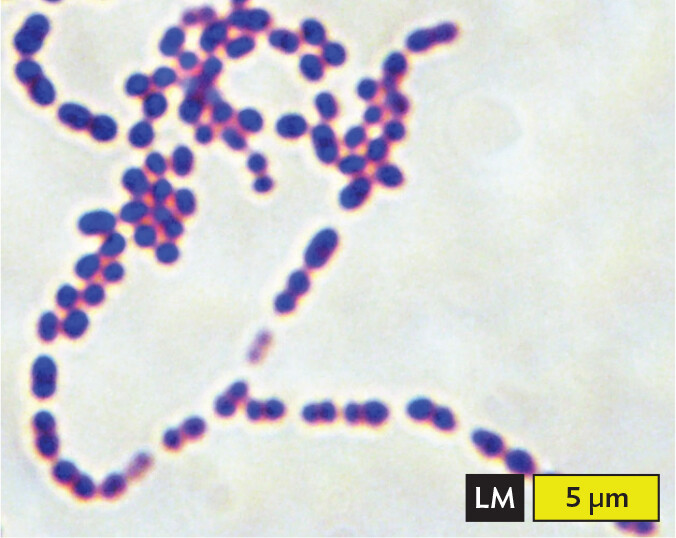

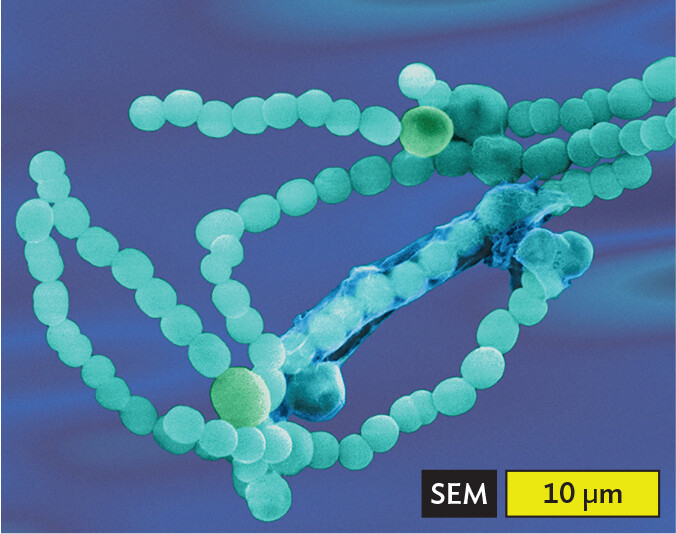

Bacterial cells. How do bacterial cells compare with cells of eukaryotes? Bacterial cell structures are generally simpler than those of eukaryotes (discussed further in Chapter 5). Figure 3.5 shows representative members of several common cell types as visualized by either light microscopy (panels A, C, E) or scanning electron microscopy (panels B, D, F). Electron microscopy is presented in Section 3.5. With light microscopy, the cell shape is barely discernible under the highest power. With scanning electron microscopy, the shapes appear clearer, but we still see no subcellular structures. Subcellular structures are best visualized with transmission electron microscopy and fluorescence microscopy (also in Section 3.5).

A light micrograph of Bacillus species, an example of filamentous rods or bacilli. Numerous round ended cylindrical cells are in the field of view. The cells are purple due to Gram staining. Each cell is about 3 micrometers in length and 0.5 micrometer in width. The cells are connected in long chains, some extending beyond the field of view.

A scanning electron micrograph of Lactobacillus acidophilus, an example of rods or bacilli. Numerous round ended cylindrical cells fill the field of view in a disorganized cluster. There is slight variation in cell length, but most of the cells are each about 2 micrometers in length and 0.5 micrometer in width.

A light micrograph of Borrelia burgdorferi, an example of a spirochete. There is a long, thin cell which appears as a wavy tapered line via light microscopy. The cell is about 15 micrometers in length and 0.5 micrometer in width. Red blood cells, which have the structure of biconcave discs, are seen near the spirochete.

A scanning electron micrograph of Leptospira interrogans, an example of a spirochete. Multiple long and thin spiral cells fill the field of view in a disorganized cluster. Each cell is roughly 10 micrometers in length and 0.5 micrometer in width.

A light micrograph of Streptococcus pneumoniae, an example of cocci in chains or filaments. Numerous spherical cells are arranged into long chains in the field of view. Each cell has a diameter of about 1 micrometer. The cells are purple due to methylene blue stain.

A scanning electron micrograph of Anabaena species of cyanobacteria, an example of cocci in chains or filaments. Numerous spherical cells are arranged into long, winding chains. Each cell has a diameter of about 2 micrometers.

Certain shapes of bacteria are common in multiple taxonomic groups (Figure 3.5). For example, both bacteria and archaea form cells of similar shapes: bacillus (plural, bacilli, rods) and coccus (plural, cocci, spheres). Thus, rods and spherical shapes have evolved independently within different taxa (groups of related organisms). On the other hand, a unique spiral shape is seen in the bacterial spirochetes, which cause diseases such as syphilis and Lyme disease. Spirochetes possess an elaborate spiral structure with internal flagella as well as an outer sheath. Spiral axial filaments are found only within the spirochete group of closely related species.

Note: The genus name Bacillus refers to a specific taxonomic group of bacteria, but the term “bacillus” (plural, bacilli) refers to any rod-shaped bacterium or archaeon.

Note: The genus name Bacillus refers to a specific taxonomic group of bacteria, but the term “bacillus” (plural, bacilli) refers to any rod-shaped bacterium or archaeon.

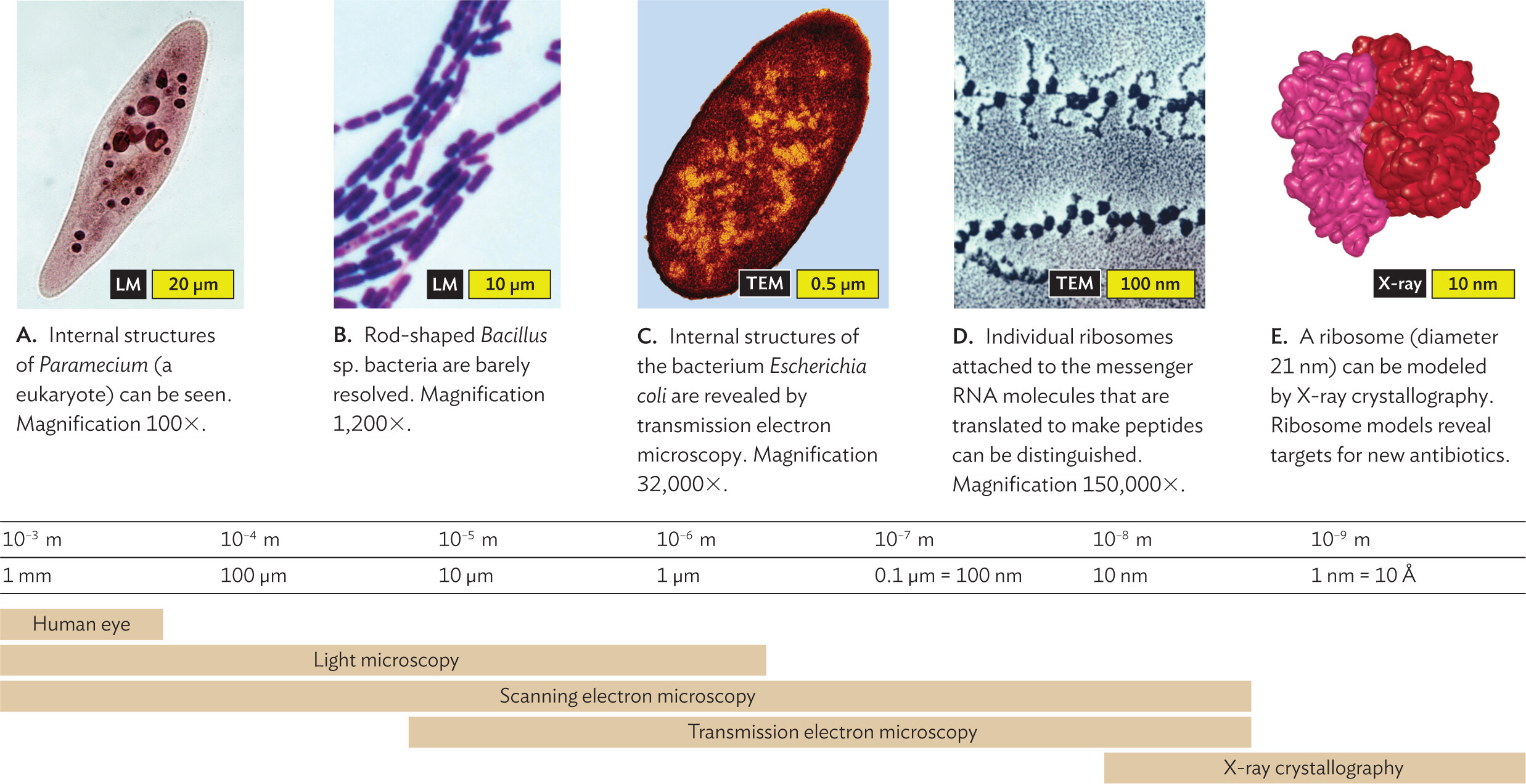

What kind of microscope do we need to observe microbes? The answer depends on the size of the object. Figure 3.6 shows how different techniques resolve microbes and structures of various sizes. For example, a single paramecium can be resolved under a light microscope, but an individual ribosome requires electron microscopy.

A series of micrographs arranged along a scale of microscopic image resolution. The micrographs are arranged from largest organism or structure to smallest organism or structure. The first micrograph shows a Paramecium at 100 X magnification. The second micrograph shows Bacillus species bacteria at 1200 X magnification. The third micrograph shows an Escherichia coli bacterium at 32000 X magnification. The fourth micrograph shows individual ribosomes attached to m R N A at 150000 X magnification. The fifth micrograph shows the structure of ribosomal subunits via X ray crystallography. Beneath the micrographs is a scale of microscopic image resolution and structural size visualization capabilities. The human eye has a resolving power between 10 superscript negative 3 meters to 10 superscript negative 4 meters. It is able to view structures between 1 millimeter to greater than 100 micrometers in size. Light microscopy has a resolving power that ranges from 10 superscript negative 3 meters to 10 superscript negative 6 meters. Structures ranging from 1 millimeter to less than 1 micrometer can be visualized. Scanning electron microscopy has a resolving power that ranges from 10 superscript negative 3 meters to 10 superscript negative 8 meters. Structures ranging from 1 millimeter to less than 10 nanometers can be visualized. Transmission electron microscopy has a resolving power that ranges from 10 superscript negative 5 meters to 10 superscript negative 8 meters. Structures ranging from 10 micrometers to less than 10 nanometers can be visualized. X ray crystallography has a resolving power ranging from 10 superscript negative 8 meters to 10 superscript negative 9 meters. Structures ranging from 10 nanometers to less than 1 nanometer can be visualized.

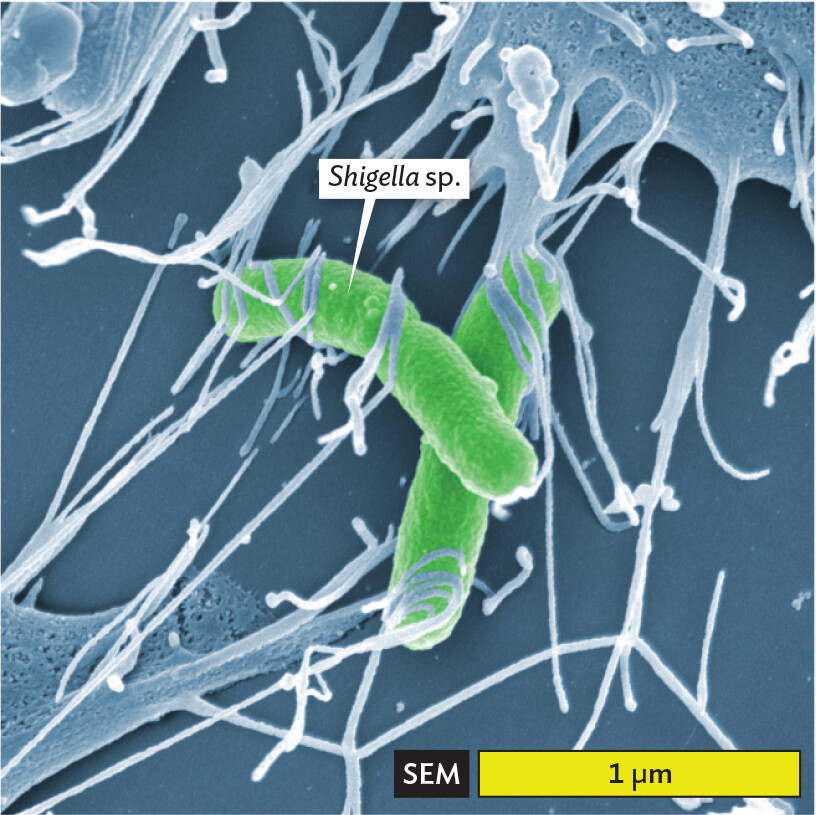

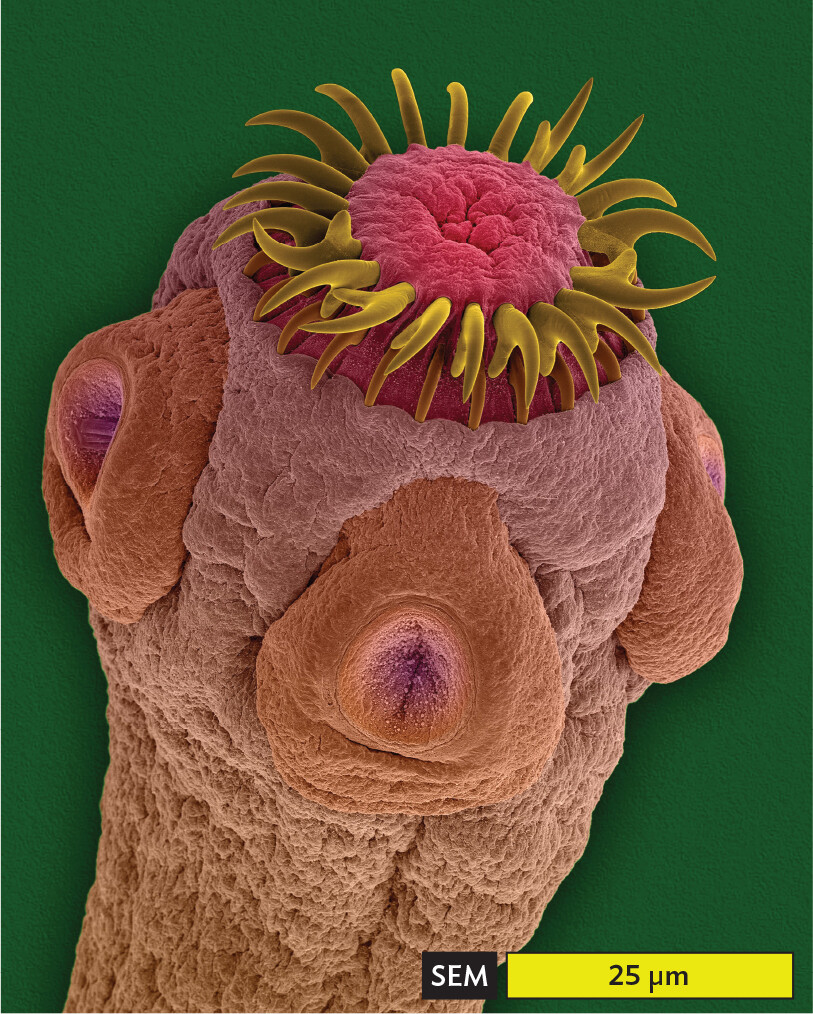

Of all these methods, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) visualizes an exceptionally wide range of sizes (Figure 3.7). For example, SEM reveals the 1-to-2-µm-sized cells of Shigella species, a cause of shigellosis diarrhea (Figure 3.7A). Shigella bacteria infect 450,000 people annually in the United States. Within the intestine, the bacteria become entwined by filopodia (cytoplasmic extensions) of the gut epithelial cells, which internalize the Shigella cells. This process enables the invasive growth of Shigella. In the micrograph, note that green colorization (or “false color”) has been added by the photo artist to emphasize the bacteria. At a much larger scale, SEM depicts the multicellular scolex (head) of a tapeworm (Figure 3.7B, colorized). The tapeworm’s hooks and suckers enable it to attach to the interior lining of the gut. When interpreting a micrograph, always check the scale bar to be aware of what size you are seeing.

A scanning electron micrograph of Shigella bacteria. There are two rod shaped bacteria amongst many sticky thread like structures. The micrograph allows for slight visualization of the textured outer surfaces of the cells. Portions of larger cell bodies are seen in the edges of the field of view. The stringy appendages appear to extend from these and stick onto the bacteria. Each bacterium is about 1.5 micrometer in length and 0.25 micrometer in width.

A scanning electron micrograph of the scolex of a tapeworm. The micrograph allows for a highly detailed view of the head structure of a tapeworm. The cylindrical tapeworm reaches a differently colored tip with a ring of yellow tuft like projections emerging from it. This tip part is connected to a wider head section that has three flat oval shaped appendages attached to its outside surface. Each appendage has a circular depression in its center. This head section then thins a bit into the body and extends out of the field of view. The widest part of the worm is about 40 micrometers, while the narrowest part is about 30 micrometers.

SECTION SUMMARY