Conclusion

Despite the intermixing of peoples, ideas, and goods across Afro-Eurasia, new political and cultural boundaries were developing that would split this landmass in ways previously unimaginable. The most important dividing force was religion, as Islam challenged and slowed the spread of Christianity and as Buddhism confronted the ruling elite of Tang China. Afro-Eurasia’s major cultural zones began to compete in terms of religious and cultural doctrines. The Abbasid Empire pushed back the borders of the Tang Empire. But the conflict grew intense between Muslim and Christian worlds, where the clash involved faith as well as frontiers. The Mediterranean Sea was quickly becoming a dividing line between Islam and Christianity.

Internally, the Tang Empire revived Confucianism, insisting on its political and moral primacy as the foundation of a new imperial order, and it embraced the classical written language as another unifying element. By doing so, the Tang counteracted the influence of universalizing foreign religions—notably Buddhism but also Islam—spreading into the Chinese state. The same adaptive strategies influenced new systems on the Korean Peninsula and in Japan.

In some circumstances, faith followed empire and the rulers’ support or tolerance of a particular religion helped spread the word. This was the case especially in East Asia. In others, empire followed faith, as in the Islamic world, where believers felt divinely inspired to spread their empire in every direction. The Islamic caliphate and its dynastic successors represented a new force: expanding political power backed by one God whose instructions were to spread his message. In the worlds of Christianity, a common faith absorbed elements of a common culture (shared books, a language—Latin—for the learned classes). Yet Christendom’s political rulers never quite overcame peoples’ intense allegiance to local authority.

While universalizing religions expanded and common cultures grew, debate raged within each religion over foundational principles. Despite the diffusion of basic texts in “official” languages, regional variations of Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism proliferated as each belief system spread. The period from 600 to 1000 CE demonstrated that religion, reinforced by prosperity and imperial resources, could bring peoples together in unprecedented ways. But it could also, as the next chapter will illustrate, drive them apart in bloody confrontations.

After You Read This Chapter

Go to  to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

TRACING THE GLOBAL STORYLINE

FOCUS ON: Religion and Empire: The Islamic Caliphate, the Tang Dynasty, and Christendom

The Islamic Empire

- Warriors from the Arabian Peninsula defeat Byzantine and Sasanian armies and establish an Islamic empire stretching from Spain and Northwest Africa to South Asia.

- The Abbasid dynasty takes over from the Umayyads, crystallizes the main Islamic institutions of the caliphate and Islamic law, and promotes cultural achievements in religion, philosophy, and science.

- Disputes over Muhammad’s succession lead to a deep and enduring split between Sunnis and Shiites.

Tang China

- The Tang dynasty dominates East Asia and exerts a strong influence on Korea and Japan.

- Tang rulers balance Confucian and Daoist ideals with Buddhist thought and practice.

- A common written language and shared philosophy, rather than a single universalizing religion, integrate the Chinese state.

Christian Europe

- Charlemagne establishes a modest empire in part of western Europe, while the Vikings raid and trade from their homeland in Scandinavia westward to North America, southward to the Mediterranean, and eastward to the Caspian Sea.

- Nuns, monks, and Rome-based popes spread Catholic Christianity throughout western Europe.

- Constantinople-based Greek Orthodoxy survives the spread of Islam and the Viking onslaught.

KEY TERMS

THINKING ABOUT GLOBAL CONNECTIONS

- Thinking about Crossing Borders and Faith and Empire As Islam spread beyond its original Arabian context, the new religion underwent a range of developments. As Christianity and Buddhism continued to spread, these traditions experienced major changes as well. Compare the shifts that took place within Islam as it expanded (600–1000 CE) with those within Buddhism and Christianity, not only in their earlier periods (see Chapter 8) but also during the period from 600 to 1000 CE.

- Thinking about Changing Power Relationships in Terms of Faith and Empire As each of the empires discussed in this chapter matured, divisions developed within the religions that initially had helped bring unity to their respective regions. In the Abbasid world, the earlier split between Sunni and Shiite Muslims solidified. In Tang China, Buddhism and Confucianism vied for political influence. Christendom divided into the Roman Catholic west and the Greek Orthodox east. What was the exact nature of each religious disagreement? How do these divisions compare in terms of the root cause of the internal rifts and their impact in the political realm?

- Thinking about Worlds Together, Worlds Apart The empires described in this chapter reached across wide swaths of territory and interacted with vibrant societies on their margins. The peoples of Europe struggled with the onslaught of the fierce Vikings. The peoples of Tang China interacted with neighboring Korea and Japan. How does the interaction of Europe and the Vikings compare with the relations of the Tang and the external influences that they experienced? To what extent did the Abbasids contend with similar exchanges?

CHRONOLOGY

More information

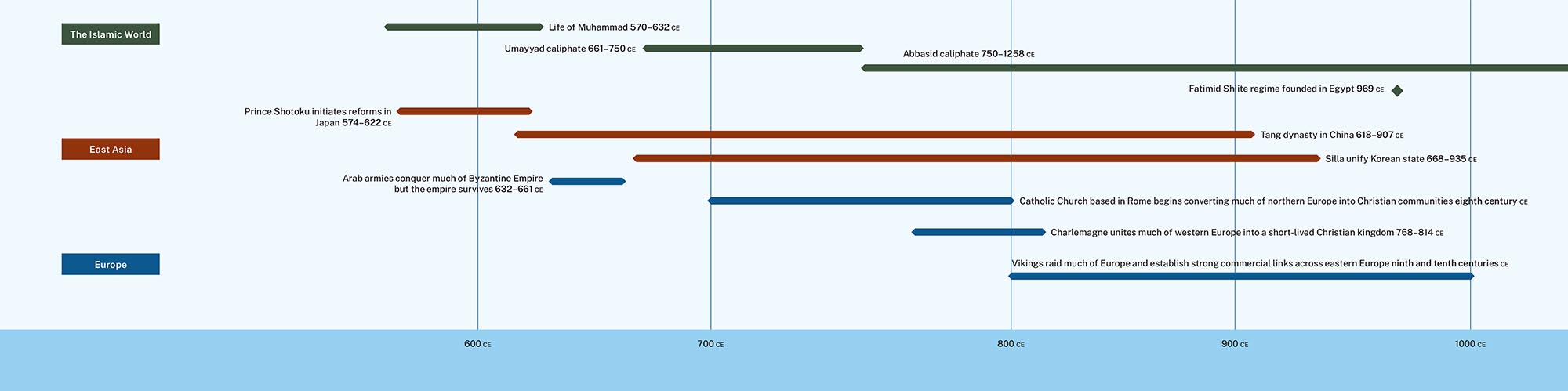

A timeline showing events from circa 600 C E to 1000 C E. The timeline shows various events represented by diamonds and lines color coded by region of the world that are situated between and around lines representing 600 C E, 700 C E, 800 C E, 900 C E, and 1000 C E. In the Islamic world, the life of Muhammad is placed at 570 to 632 C E, the Umayyad caliphate is placed at 661 to 750 C E, The Abbasid caliphate is placed at 750 to 1258 C E, and the Fatimid Chiite regime is founded in Egypt in 969 C E. In East Asia, Prince Shotoku initiates reforms in Japan in 574 to 622 C E, the Tang dynasty in China is placed at 618 to 907 C E, and Silla unifying the Korean state is placed at 668 to 935 C E. In Europe, Arab armies conquer much of the Byzantine empire but the empire survives is placed at 632 to 661 C E, the Catholic Church based in Rome begins converting much of northern Europe into Christian communities in the eighth century C E, Charlemagne unites much of western Europe into a short-lived Christian kingdom in 768 to 814 C E, and Vikings raid much of Europe and establish strong commercial links across eastern Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries C E.

Glossary

- caliphate

- Islamic state, headed by a caliph—chosen either by election from the community (Sunni) or from the lineage of Muhammad (Shiite)—with political authority over the Muslim community.

- civil service examinations

- Set of challenging exams instituted by the Tang to help assess potential bureaucrats’ literary skill and knowledge of the Confucian classics.

- eunuchs

- Surgically castrated men who rose to high levels of military, political, and personal power in several empires (for instance, the Tang and the Ming Empires in China; the Abbasid and Ottoman Empires; and the Byzantine Empire).

- five pillars of Islam

- Five practices that unite all Muslims: (1) proclaiming that “there is no God but God and Muhammad is His Prophet”; (2) praying five times a day; (3) fasting during the daylight hours of the holy month of Ramadan; (4) traveling on pilgrimage to Mecca; and (5) paying alms to support the poor.

- Greek Orthodoxy

- Branch of eastern Christianity, originally centered in Constantinople, that emphasizes the role of Jesus in helping humans achieve union with God.

- monasticism

- From the Greek word monos (meaning “alone”), the practice of living without the ties of marriage or family, forsaking earthly luxuries for a life of prayer and study. While Christian monasticism originated in Egypt, a variant of ascetic life had long been practiced in Buddhism.

- Roman Catholicism

- Western European Christianity, centered on the papacy in Rome, that emphasizes the atoning power of Jesus’s death and aims to expand as far as possible.

- sharia

- Shiites

- Minority tradition within modern Islam that traces political succession through the lineage of Muhammad and breaks with Sunni understandings of succession at the death of Ali (cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad and fourth caliph) in 661 CE.

- Sunnis

- Majority sect within modern Islam that follows a line of political succession from Muhammad, through the first four caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali), to the Umayyads and beyond, with caliphs chosen by election from the umma (not from Muhammad’s direct lineage).

- Vikings

- Warrior group from Scandinavia that used its fighting skills and sophisticated ships to raid and trade deep into eastern Europe, southward into the Mediterranean, and westward to Iceland, Greenland, and North America.