3

Polyphony through the Thirteenth Century

CHAPTER OUTLINE

PRELUDE

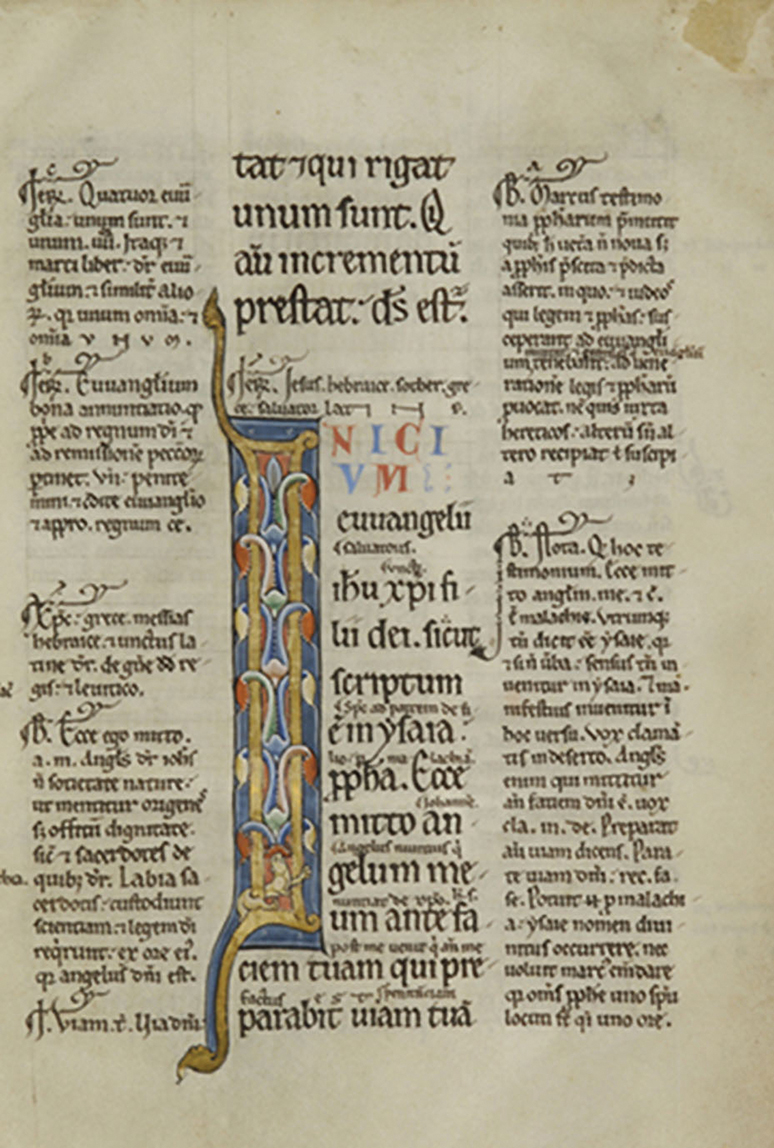

The years 1050 to 1300 saw an increase in trading and commerce throughout western Europe, as its growing population began to build modern cities. The Normans (a warrior people originally from Scandinavia who settled Normandy in northern France) crossed the English Channel to capture England, while Spain was seeking to liberate itself from Muslim conquerors. The First Crusade (1095–99) united Christian ruling families from all over Europe in a successful campaign to drive the “infidel” Turks out of Jerusalem. After centuries of political instability and limited literacy, Europe enjoyed a cultural revival, which included music and all the arts; we have seen some of its effects in the eloquent love songs of the troubadours and trouvères. Scholars translated important works from Greek antiquity and the Arab world into Latin, encouraging the development of music theory. Places of teaching and learning that eventually became universities sprang up in Paris, Oxford, and Bologna. Large Romanesque churches (see Figure I.6), built on the architectural principle of the round arch of the Roman basilica, began to dominate the landscape, just as Gregorian chant and the Roman rite had prevailed in the liturgy. Pious donors funded hundreds of new monasteries and convents, filled by rising numbers of men, women, and children seeking a religious life. As scholars revived ancient learning, Saint Anselm, Saint Thomas Aquinas, and others associated with the intellectual movement called Scholasticism sought to reconcile classical philosophy with Christian doctrine through commentary on authoritative texts (see Figure 3.1). The Romanesque style yielded to a new style of church architecture called Gothic, which emphasized height and spaciousness, with soaring vaults, pointed arches, slender columns, large stained-glass windows, and intricate carvings (see Figure 3.4). Some of these developments found parallels in the art of written polyphony, which blossomed in certain regions of France and England in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (see In Context, p. 62).

By polyphony, we mean music in which voices sing together in independent parts. At first, polyphony was a style of performance, a manner of accompanying chant with one or more added voices. This heightened the grandeur of chant and, thus, of the liturgy itself, just as art and architectural decoration ornamented the church and, thus, the service. The added voices elaborated the authorized chants by providing a musical gloss or commentary, a process resembling troping; and, indeed, polyphony developed in the same regions and contexts as the monophonic tropes discussed in Chapter 2. Therefore, the kind of polyphony we associate with Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris has roots in a long prehistory of improvised polyphony, of which few written traces exist. We have good reason to believe that European musicians used polyphony in and outside of church long before it was first unmistakably described in a ninth-century treatise called Musica enchiriadis (Music Handbook).

More information

(The Pierpont Morgan Library/Art Resource, NY.)

When, in the ninth century, singers improvising on plainchant departed from simple parallel motion to give their parts some independence, they set the stage for counterpoint, the combination of multiple independent lines. The need for regulation of these simultaneous sounds led eventually to the precepts of harmony. As the parts were combined in more complex ways, refinements in notation permitted music to be written down and performed repeatedly. Written composition began to replace improvisation as a way of creating musical works, and notation began to replace memory as a means of preserving them. Consequently, the rise of written polyphony is of particular interest because it inaugurated four concepts that have distinguished Western music ever since: (1) counterpoint, the combination of multiple independent lines; (2) harmony, the regulation of simultaneous sounds; (3) the centrality of notation; and (4) the idea of composition as distinct from performance. These concepts changed over time, but their presence in this music links it to all that followed.

Such changes came about gradually during the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries; there was no sudden break with the past. Monophony remained the principal medium of both performance and new composition. Indeed, some of the finest monophonic chants, including antiphons, hymns, and sequences, were produced after 1200, some as late as the sixteenth century. Musicians continued to improvise as well, and many stylistic details of the polyphonic music that remains in written form grew out of improvisational practice.

After developments traceable from the ninth century, several types of polyphony gained a secure place in the extant written repertories of France and England. We will study two of them in this chapter: organum and motet. Organum (pronounced or'-ga-num; pl. or'-ga-na) was, as we have suggested, a form of troping the chant. But now, instead of attaching a melodic trope to the beginning or end of an existing chant — a horizontal extension — organum offered the possibility of adding new layers of melody in a vertical dimension. This polyphonic elaboration of plainchant reached its most sophisticated level in Paris at Notre Dame Cathedral, a church built in the soaring, new Gothic style of the twelfth century (see Figure 3.4). By creating different rates of motion among the voice parts, singers at Notre Dame forced a breakthrough in rhythmic notation, which until then had been vague at best. They also began creating other polyphonic genres, the most enduring among them being the motet, which also had its origins in the process of troping, as we shall see. The motet eventually became the dominant genre of both sacred and secular polyphonic music.