THE DISCOVERY OF MACROMOLECULES

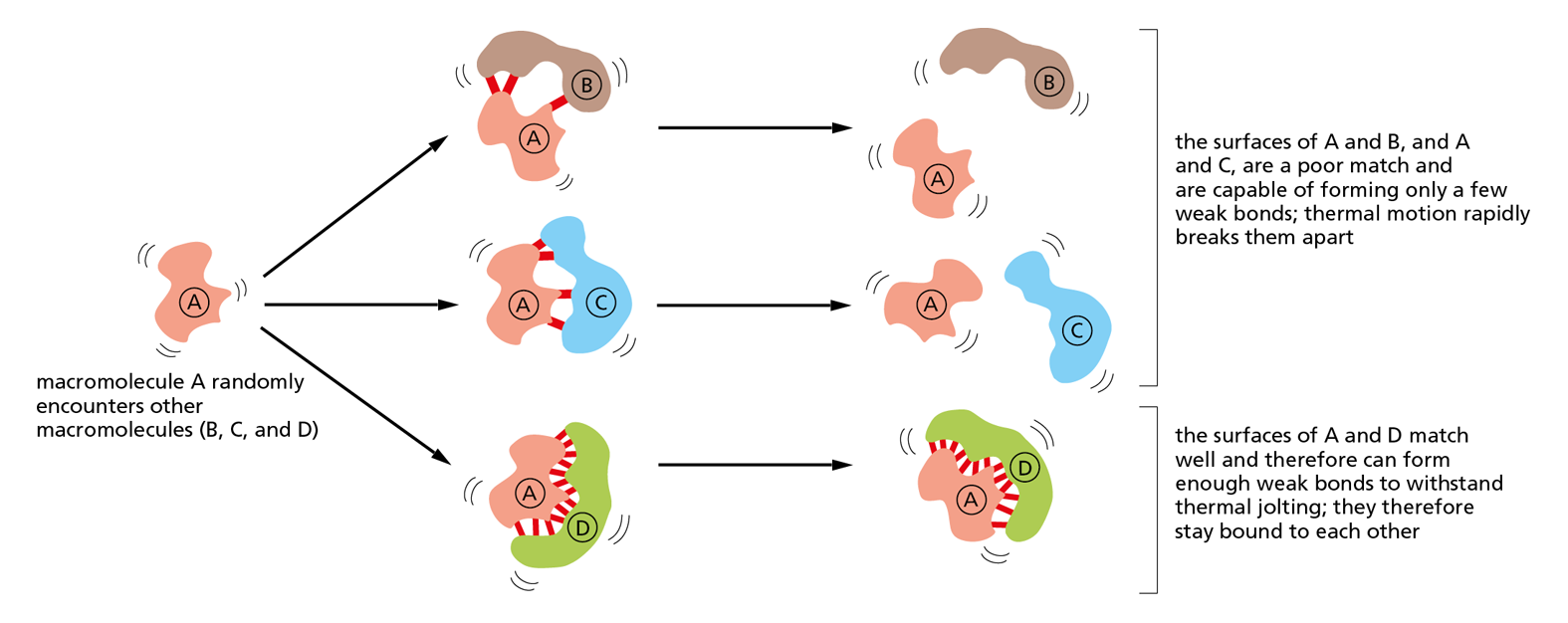

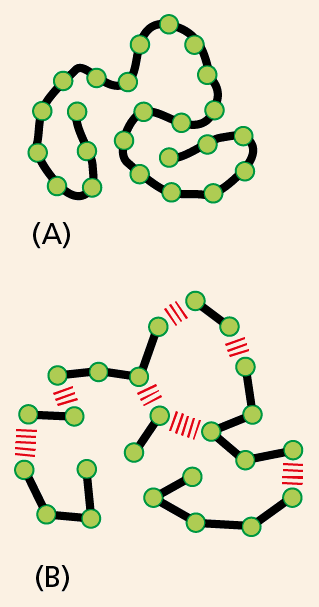

The idea that proteins, polysaccharides, and nucleic acids are large molecules that are constructed from smaller subunits, linked one after another into long molecular chains, may seem fairly obvious today. But this was not always the case. In the early part of the twentieth century, few scientists believed in the existence of such biological polymers built from repeating units held together by covalent bonds. The notion that such “frighteningly large” macromolecules could be assembled from simple building blocks was considered “downright shocking” by chemists of the day. Instead, they thought that proteins and other seemingly large organic molecules were simply heterogeneous aggregates of small organic molecules held together by weak “association forces” (Figure 2–32).

Figure 2–32 What might an organic macromolecule look like? Chemists in the early part of the twentieth century debated whether proteins, polysaccharides, and other apparently large organic molecules were (A) discrete particles made of an unusually large number of covalently linked atoms or (B) a loose aggregation of heterogeneous small organic molecules held together by weak forces.

The first hint that proteins and other organic polymers are large molecules came from observing their behavior in solution. At the time, scientists were working with various proteins and carbohydrates derived from foodstuffs and other organic materials—albumin from egg whites, casein from milk, collagen from gelatin, and cellulose from wood. Their chemical compositions seemed simple enough: like other organic molecules, they contained carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and, in the case of proteins, nitrogen. But they behaved oddly in solution, showing, for example, an inability to pass through a fine filter.

Why these molecules misbehaved in solution was a puzzle. Were they really giant molecules, composed of an unusually large number of covalently linked atoms? Or were they more like a colloidal suspension of particles—a big, sticky hodgepodge of small organic molecules that associate only loosely?

One way to distinguish between the two possibilities was to determine the actual size of one of these molecules. If a protein such as albumin were made of molecules all identical in size, that would support the existence of true macromolecules. Conversely, if albumin were instead a miscellaneous conglomeration of small organic molecules, these should show a whole range of molecular sizes in solution.

Unfortunately, the techniques available to scientists in the early 1900s were not ideal for measuring the sizes of such large molecules. Some chemists estimated a protein’s size by determining how much it would lower a solution’s freezing point; others measured the osmotic pressure of protein solutions. These methods were susceptible to experimental error and gave variable results. Different techniques, for example, suggested that cellulose was anywhere from 6000 to 103,000 daltons in mass (where 1 dalton is approximately equal to the mass of a hydrogen atom). Such results helped to fuel the hypothesis that carbohydrates and proteins were loose aggregates of small molecules rather than true macromolecules.

Many scientists simply had trouble believing that molecules heavier than about 4000 daltons—the largest compound that had been synthesized by organic chemists—could exist at all. Take hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Researchers tried to estimate its size by breaking it down into its chemical components. In addition to carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen, hemoglobin contains a small amount of iron. Working out the percentages, it appeared that hemoglobin had one atom of iron for every 712 atoms of carbon—and a minimum weight of 16,700 daltons. Could a molecule with hundreds of carbon atoms in one long chain remain intact in a cell and perform specific functions? Emil Fischer, the organic chemist who determined that the amino acids in proteins are linked by peptide bonds, thought that a polypeptide chain could grow no longer than about 30 or 40 amino acids. As for hemoglobin, with its purported 700 carbon atoms, the existence of molecular chains of such “truly fantastic lengths” was deemed “very improbable” by leading chemists.

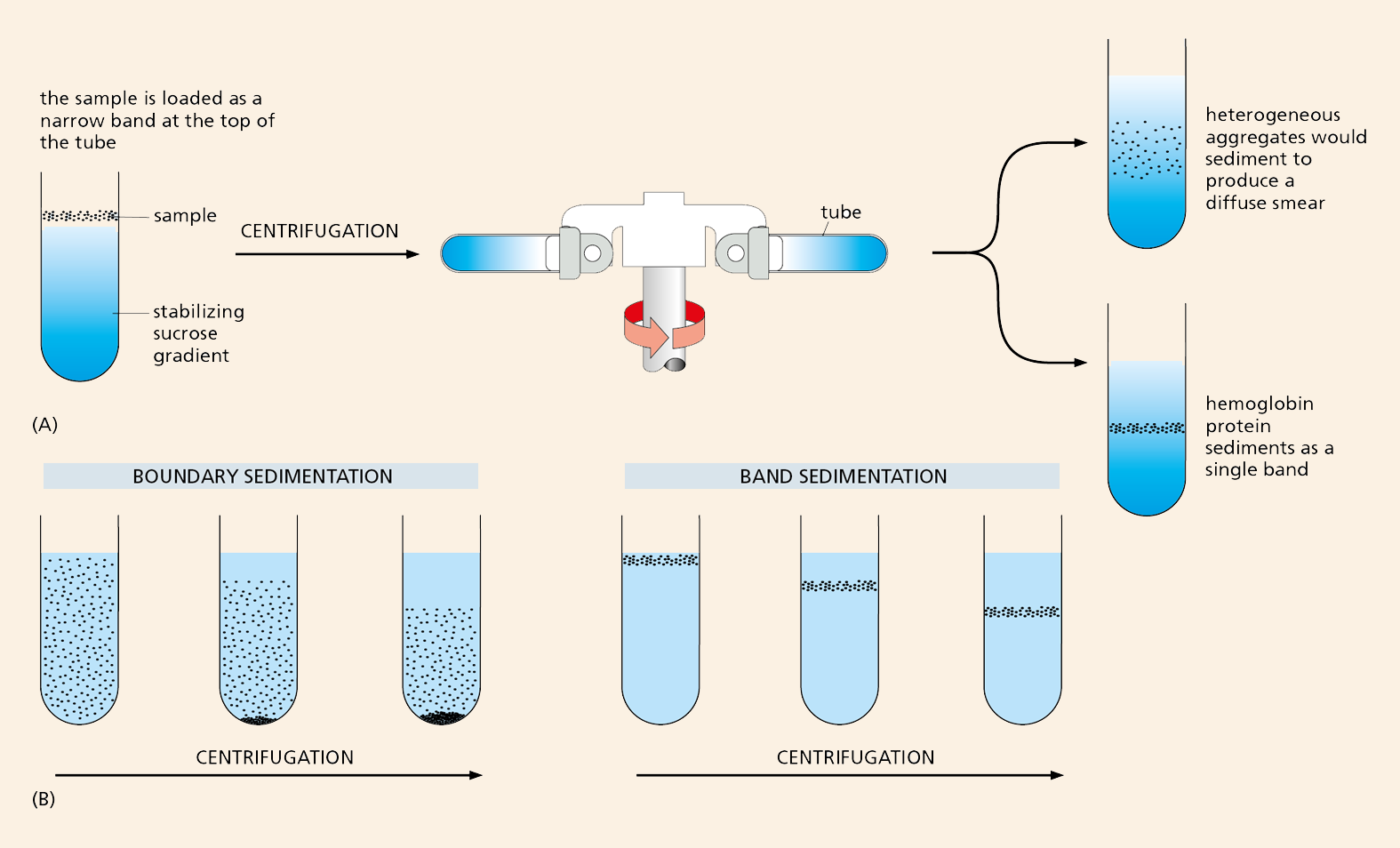

Definitive resolution of the debate had to await the development of new techniques. Convincing evidence that proteins are macromolecules came from studies using the ultracentrifuge—a device that uses centrifugal force to separate molecules according to their size (see Panel 4–3, pp. 164–165). Theodor Svedberg, who designed the machine in 1925, performed the first studies. If a protein were really an aggregate of smaller molecules, he reasoned, it would appear as a smear of molecules of different sizes when sedimented in an ultracentrifuge. Using hemoglobin as his test protein, Svedberg found that the centrifuged sample revealed a single, sharp band with a molecular weight of 68,000 daltons. The finding strongly supported the theory that proteins are true macromolecules (Figure 2–33).

Figure 2–33 The ultracentrifuge helped to settle the debate about the nature of macromolecules. In the ultracentrifuge, centrifugal forces exceeding 500,000 times the force of gravity can be used to separate proteins or other large molecules. (A) In a modern ultracentrifuge, samples are loaded in a thin layer on top of a gradient of sucrose solution formed in a tube. The tube is placed in a metal rotor that is rotated at high speed in a vacuum. Molecules of different sizes sediment at different rates, and these molecules will therefore move as distinct bands in the sample tube. If hemoglobin were a loose aggregate of heterogeneous peptides, it would show a broad smear of sizes after centrifugation (top tube). Instead, it appears as a sharp band with a molecular weight of 68,000 daltons (bottom tube). Although the ultracentrifuge is now a standard, almost mundane, fixture in most biochemistry laboratories, its construction was a huge technological challenge. The centrifuge rotor must be capable of spinning centrifuge tubes at high speeds for many hours at constant temperature and with high stability to avoid disrupting the gradient and ruining the samples. In 1926, Svedberg won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his ultracentrifuge design and its application to chemistry. (B) In his actual experiment, Svedberg filled a special tube in the centrifuge with a homogeneous solution of hemoglobin; by shining light through the tube, he then carefully monitored the moving boundary between the sedimenting protein molecules and the clear aqueous solution left behind (so-called boundary sedimentation). The more recently developed method shown in (A) is a form of band sedimentation.

Additional evidence continued to accumulate throughout the 1930s, when other researchers were able to obtain crystals of pure protein that could be studied by x-ray diffraction. Only molecules with a uniform size and shape can form highly ordered crystals and diffract x-rays in such a way that their three-dimensional structure can be determined, as we discuss in Chapter 4. A heterogeneous suspension could not be studied in this way.

We now take it for granted that large macromolecules carry out many of the most important activities in living cells. But chemists once viewed the existence of such polymers with the same sort of skepticism that a zoologist might show on being told that “In Africa, there are elephants that are 100 meters long and 20 meters tall.” It took decades for researchers to master the techniques required to convince everyone that molecules ten times larger than anything they had ever encountered were a cornerstone of biology. As we shall see throughout this book, such a labored pathway to discovery is not unusual, and progress in science—as in the discovery of macromolecules—is often driven by advances in technology.