|

chapter Four |

4 |

|

chapter Four |

4 |

The Shape and Structure of Proteins

When we look at a cell in a microscope or analyze its electrical or biochemical activity, we are, in essence, observing the handiwork of proteins. Proteins are the main building blocks from which cells are assembled, and they constitute most of the cell’s dry mass. In addition to providing the cell with shape and structure, proteins also execute nearly all its myriad functions. Enzymes promote intracellular chemical reactions by providing intricate molecular surfaces contoured with particular bumps and crevices that can cradle or exclude specific molecules. Transporters and channels embedded in the plasma membrane control the passage of nutrients and other small molecules into and out of the cell. Other proteins carry messages from one cell to another, or act as signal integrators that relay information from the plasma membrane to the nucleus of individual cells. Some proteins act as motors that propel organelles through the cytosol, and others function as components of tiny molecular machines with precisely calibrated moving parts. Specialized proteins also act as antibodies, toxins, hormones, antifreeze molecules, elastic fibers, or luminescence generators. To understand how muscles contract, how nerves conduct electricity, how embryos develop, or how our bodies function, we must first understand how proteins operate.

The multiplicity of functions carried out by these remarkable macromolecules, a few of which are represented in Panel 4−1, p. 118, arises from the huge number of different shapes proteins adopt. We therefore begin our description of proteins by discussing their three-dimensional structures and the properties that these structures confer. We next look at how proteins work: how enzymes catalyze chemical reactions, how some proteins act as molecular switches, and how others generate orderly movement. We then examine how cells control the activity and location of the proteins they contain. Finally, we present a brief description of the techniques that biologists use to work with proteins, including methods for purifying them—from tissues or cultured cells—and for determining their structures.

|

Panel 4–1 |

a few examples of some general protein functions |

function: Catalyze covalent bond breakage or formation

examples: Living cells contain thousands of different enzymes, each of which catalyzes (speeds up) one particular reaction. Examples include: alcohol dehydrogenase—makes the alcohol in wine; pepsin—degrades dietary proteins in the stomach; ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase—helps convert carbon dioxide into sugars in plants; DNA polymerase—copies DNA; protein kinase — adds a phosphate group to a protein molecule.

function: Provide mechanical support to cells and tissues

examples: Outside cells, collagen and elastin are common constituents of extracellular matrix and form fibers in tendons and ligaments. Inside cells, tubulin forms long, stiff microtubules, and actin forms filaments that underlie and support the plasma membrane; keratin forms fibers that reinforce epithelial cells and is the major protein in hair and horn.

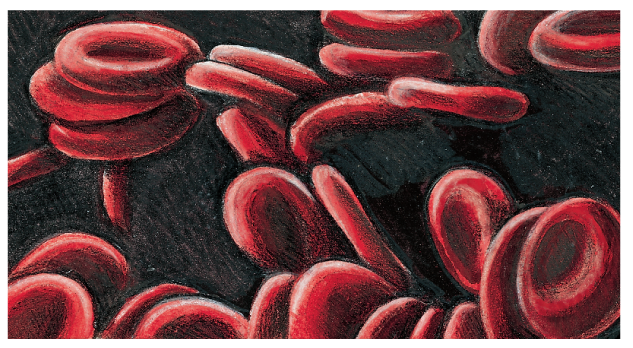

function: Carry small molecules or ions

examples: In the bloodstream, serum albumin carries lipids, hemoglobin carries oxygen, and transferrin carries iron. Many proteins embedded in cell membranes transport ions or small molecules across the membrane. For example, the bacterial protein bacteriorhodopsin is a light-activated proton pump that transports H+ ions out of the cell; glucose transporters shuttle glucose into and out of cells; and a Ca2+ pump clears Ca2+ from a muscle cell’s cytosol after the ions have triggered a contraction.

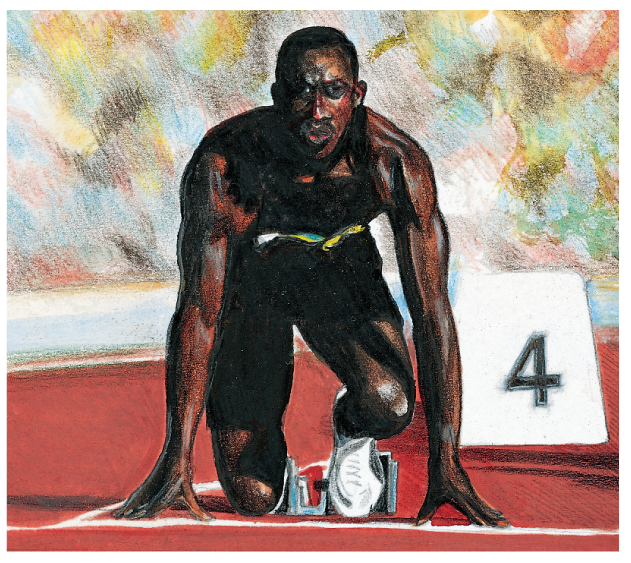

function: Generate movement in cells and tissues

examples: Myosin in skeletal muscle cells provides the motive force for humans to move; kinesin interacts with microtubules to move organelles around the cell; dynein enables eukaryotic cilia and flagella to beat.

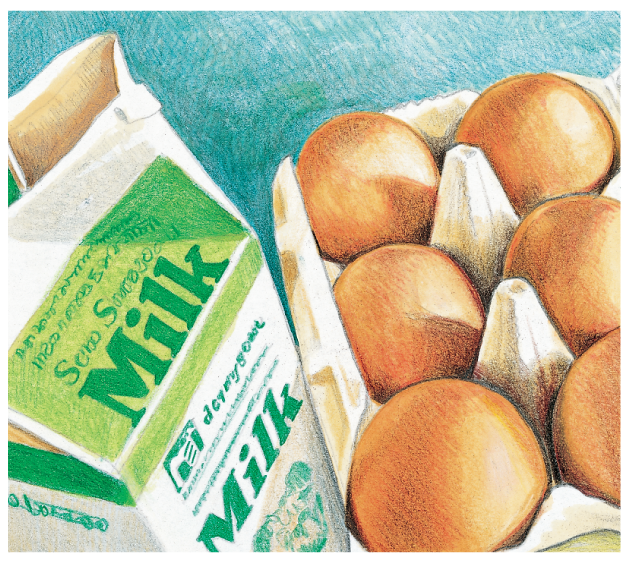

function: Store amino acids or ions

examples: Iron is stored in the liver by binding to the small protein ferritin; ovalbumin in egg white is used as a source of amino acids for the developing bird embryo; casein in milk is a source of amino acids for baby mammals.

function: Carry extracellular signals from cell to cell

examples: Many of the hormones and growth factors that coordinate physiological functions in animals are proteins. Insulin, for example, is a small protein that controls glucose levels in the blood; netrin attracts growing nerve cell axons to specific locations in the developing spinal cord; nerve growth factor (NGF) stimulates some types of nerve cells to grow axons; epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulates the growth and division of epithelial cells.

function: Detect signals and transmit them to the cell's response machinery

examples: Rhodopsin in the retina detects light; the acetylcholine receptor in the membrane of a muscle cell is activated by acetylcholine released from a nerve ending; the insulin receptor allows a cell to respond to the hormone insulin by taking up glucose; the adrenergic receptor on heart muscle increases the rate of the heartbeat when it binds to epinephrine secreted by the adrenal gland.

function: Bind to DNA to switch genes on or off

examples: The Lac repressor in bacteria silences the genes for the enzymes that degrade the sugar lactose; many different DNA-binding proteins act as genetic switches to control development in multicellular organisms, including humans.

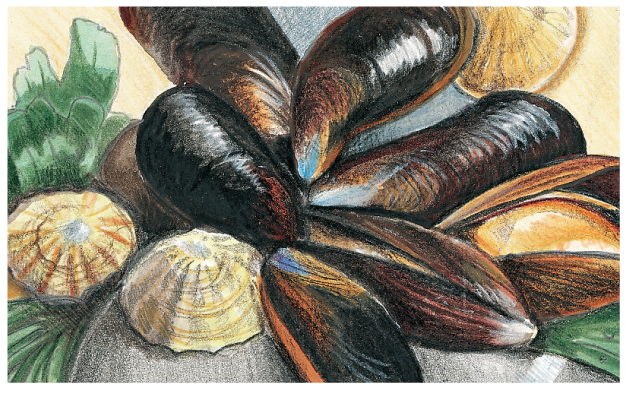

function: Highly variable

examples: Organisms make many proteins with highly specialized properties. These molecules illustrate the amazing range of functions that proteins can perform. The antifreeze proteins of Arctic and Antarctic fishes protect their blood against freezing; green fluorescent protein from jellyfish emits a green light; monellin, a protein found in an African plant, has an intensely sweet taste; mussels and other marine organisms secrete glue proteins that attach them firmly to rocks, even when immersed in seawater.