MUSIC THEORY AND PRACTICE

THE TRANSMISSION OF GREEK MUSIC THEORY

The chant repertory drew on sources in ancient Israel and in Christian communities from Syria and Byzantium in the East to Milan, Rome, and Gaul in the West. But for their understanding of this music, church musicians also drew on the music theory and philosophy of ancient Greece. During the early Christian era, this legacy was gathered, summarized, modified, and transmitted to the West, most notably by Martianus Capella and Boethius.

Martianus Capella In his widely read treatise The Marriage of Mercury and Philology (early fifth century), Martianus described the seven liberal arts: grammar, dialectic, rhetoric, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and harmonics (music). The first three, the verbal arts, came to be called the trivium (three paths), while the last four, the mathematical disciplines, were called the quadrivium (four paths) by Boethius. The section on music is a modified translation of On Music by Aristides Quintilianus. Such heavy borrowing from earlier authorities was typical of scholarly writing and remained so throughout the Middle Ages.

Boethius (ca. 480–ca. 524) was the most revered authority on music in the Middle Ages. Born into a patrician family in Rome, Boethius became consul and minister to Theodoric, Ostrogoth ruler of Italy, and wrote on philosophy, logic, theology, and the mathematical arts. His De institutione musica (The Fundamentals of Music), written when Boethius was a young man and widely copied and cited for the next thousand years, treats music as part of the quadrivium. Music for Boethius is a science of numbers, and numerical ratios and proportions determine intervals, consonances, scales, and tuning. Boethius compiled the book from Greek sources, mainly a lost treatise by Nicomachus and the first book of Ptolemy’s Harmonics. Although medieval readers may not have realized how much Boethius depended on other authors, they understood that his statements rested on Greek mathematics and music theory.

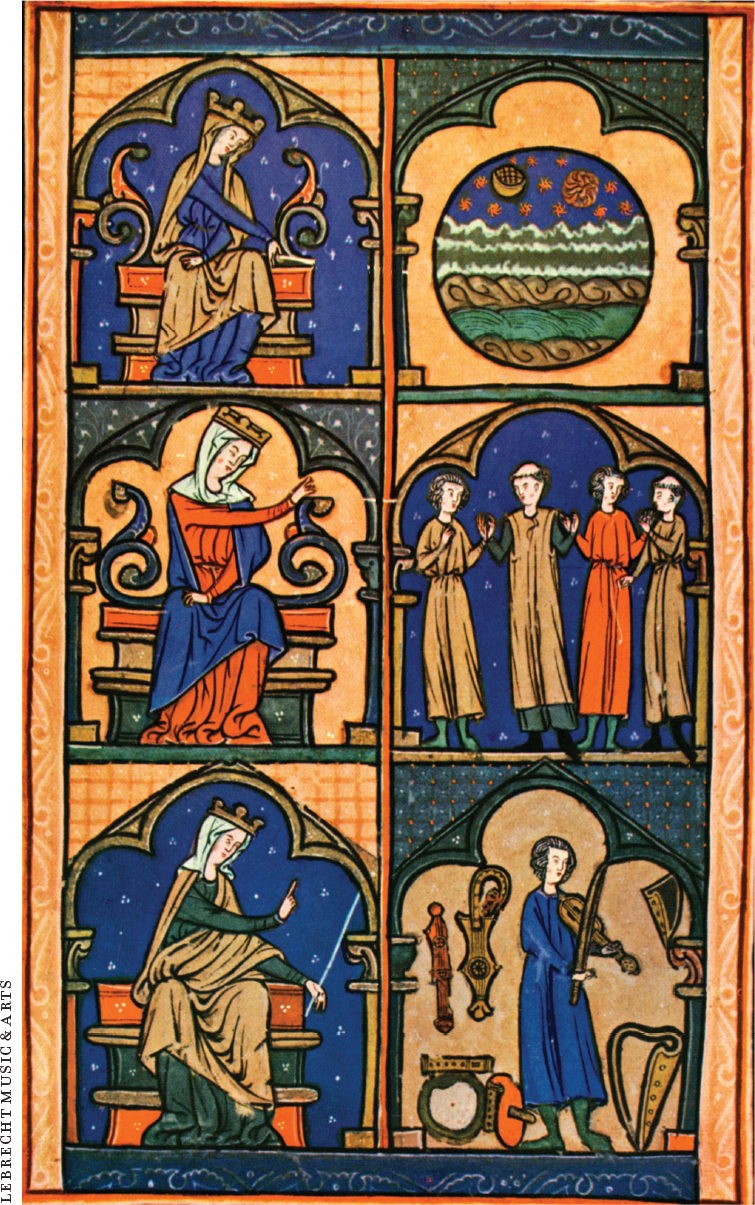

The most original part of his book is the opening chapters, where Boethius divides music into three types, depicted in Figure 2.9. The first type he calls musica mundana (the music of the universe), the numerical relations controlling the movement of stars and planets, the changing of the seasons, and the elements. Second is musica humana (human music), which harmonizes and unifies the body and soul and their parts. Last is musica instrumentalis (instrumental music), audible music produced by instruments or voices, which exemplifies the same principles of order, especially in the numerical ratios of musical intervals.

Boethius emphasized the influence of music on character. As a consequence, he believed music was important in educating the young, both in its own right and as an introduction to more-advanced philosophical studies. He valued music primarily as an object of knowledge, not a practical pursuit. For him music was the study of high and low sounds by means of reason and the senses; the philosopher who used reason to make judgments about music was the true musician, not the singer or someone who made up songs by instinct.

PRACTICAL THEORY

Treatises from the ninth century through the later Middle Ages were more oriented toward practical concerns than were earlier writings. Boethius was mentioned with reverence, and the mathematical fundamentals of music that he transmitted still undergirded the treatment of intervals, consonances, and scales. But discussions of music as a liberal art did not help church musicians notate, read, classify, and sing plainchant or improvise or compose polyphony. These latter topics now dominated the treatises.

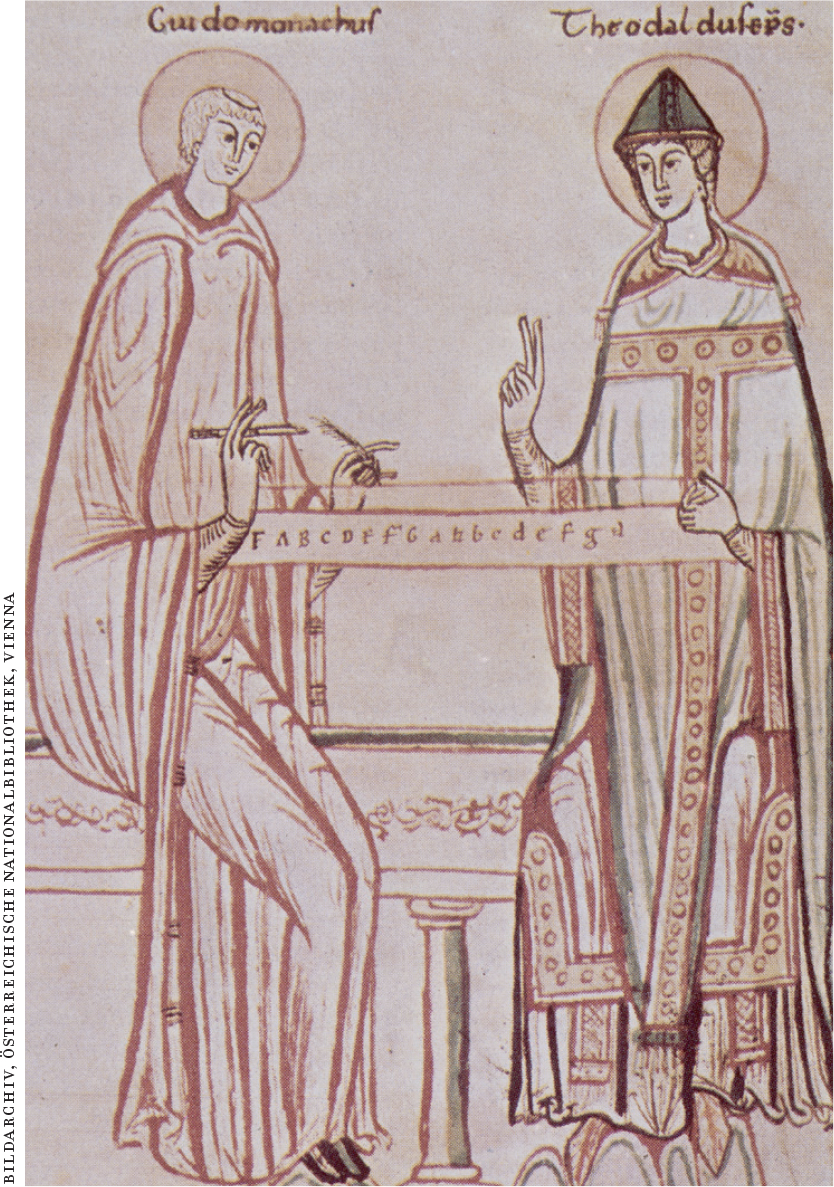

Musica enchiriadis and Micrologus Among the most important treatises were the anonymous ninth-century Musica enchiriadis (Music Handbook) and an accompanying dialogue, Scolica enchiriadis (Comments on the Handbook). Both are directed at students who aspired to enter clerical orders, the former focusing on training singers, the latter combining such practical matters with mathematical approaches as a bridge to the quadrivium. Musica enchiriadis describes eight modes (see pp. 36–39), provides exercises for locating semitones in chant, and explains the consonances and how they are used to sing in polyphony (see Chapter 5). The most widely read treatise after Boethius was Guido of Arezzo’s Micrologus (ca. 1025–28), a practical guide for singers that covers notes, intervals, the eight modes, melodic composition, and improvised polyphony. It was commissioned by the bishop of Arezzo, shown with Guido in Figure 2.10.

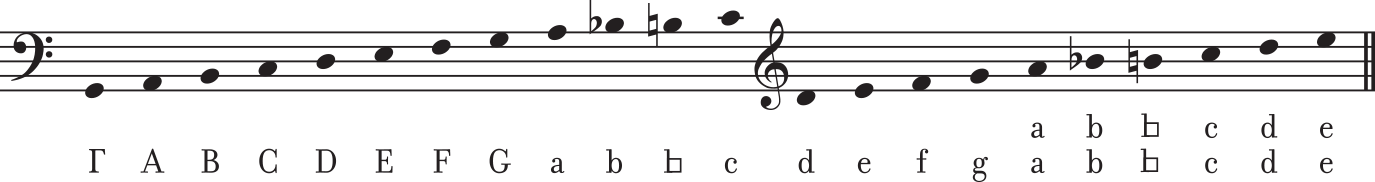

Letter names for notes The medieval tone-system was based on the Greater and Lesser Perfect Systems of ancient Greece in the diatonic genus (see Chapter 1, pp. 14–15 and Example 1.2). Early medieval theorists used the Greek names for notes. In the late tenth century, a northern Italian treatise, Dialogus de musica (Dialogue on Music), introduced a simpler letter notation that was adopted by Guido of Arezzo and became the basis for our modern practice of naming notes using the letters A to G in every octave. As shown in Example 2.4, uppercase letters (A–G) were used for the bottom seven notes of the Greater Perfect System, lowercase letters (a–g) for the next octave, and double letters above that. The note a whole step below A was written Γ (the Greek letter gamma, equivalent to G), and Guido extended the range up to  , beyond the two octaves of the Greek system. One difference between the Greater and Lesser Perfect Systems was whether the note above the mese (a) was a whole tone or a semitone higher, and the new letter notation accommodated both possibilities with two forms of the letter b:

, beyond the two octaves of the Greek system. One difference between the Greater and Lesser Perfect Systems was whether the note above the mese (a) was a whole tone or a semitone higher, and the new letter notation accommodated both possibilities with two forms of the letter b:  (“square b”), indicating a whole tone above a, and

(“square b”), indicating a whole tone above a, and  (“round b”), a semitone above a. The former sign evolved into our ♮ and

(“round b”), a semitone above a. The former sign evolved into our ♮ and  signs, and the latter into our

signs, and the latter into our  sign. The new letter system was easy to learn and to use, and it has been part of musical training ever since Guido.

sign. The new letter system was easy to learn and to use, and it has been part of musical training ever since Guido.

EXAMPLE 2.4 Guido of Arezzo’s letter names for the notes of the tone-system

THE CHURCH MODES

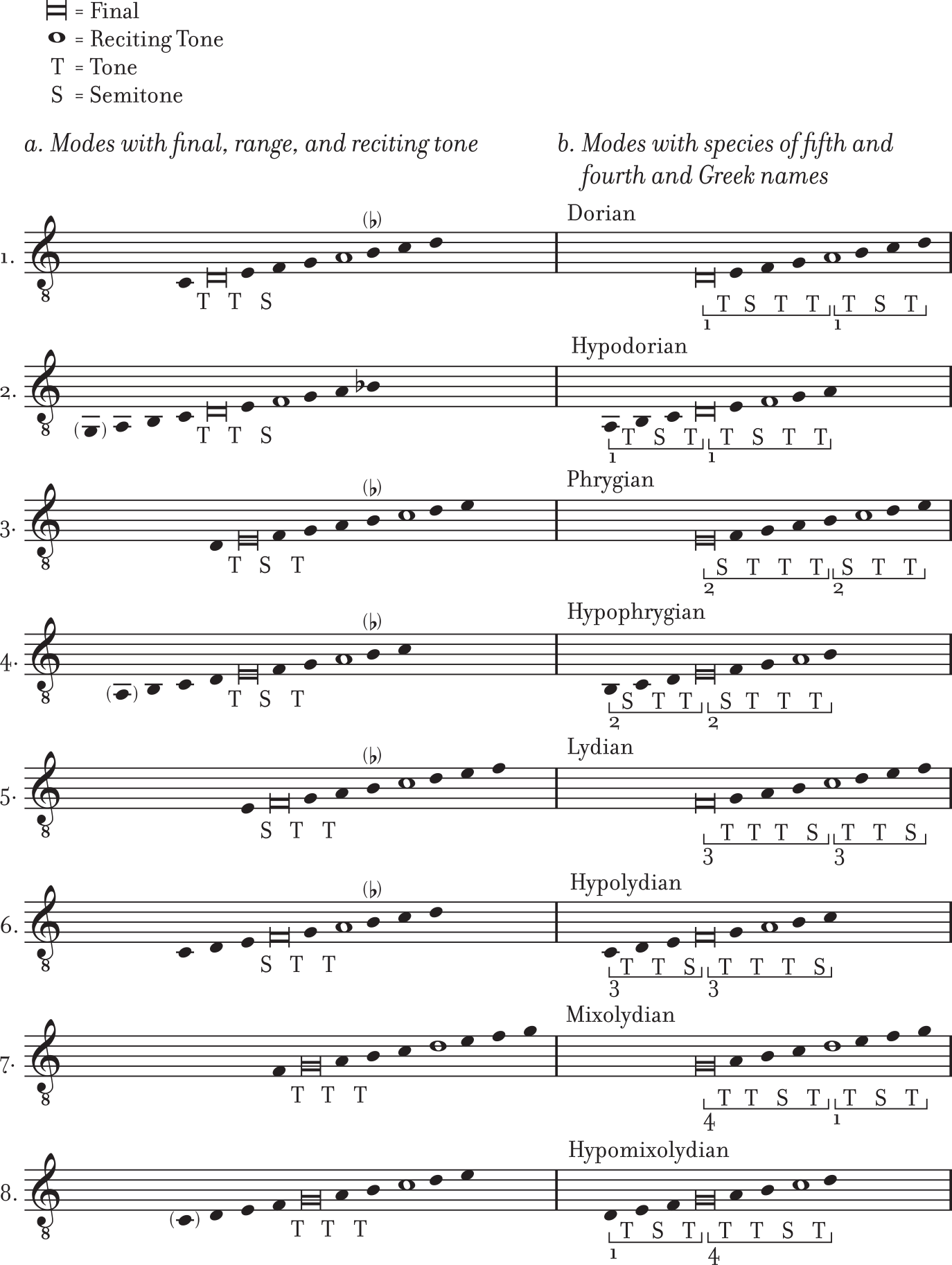

An essential component of the curriculum for church musicians was the system of eight modes, adapted from the eight echoi of Byzantine chant (see pp. 25–26). Each chant was assigned to a particular mode, and learning the modes and classifying chants by mode made it easier to learn and memorize chants. Beginning in the late eighth century, books called tonaries grouped chants by mode. Characteristic melodic gestures associated with each mode also gave musicians a clear sense of mode. The modal system evolved gradually, and writers differed in their approaches. In its complete form, achieved by the tenth century, the system encompassed eight modes identified by number. Example 2.5a shows the important characteristics of each mode, especially its final, range, and reciting tone.

The modes are differentiated by the arrangement of whole and half steps in relation to the final, the main note in the mode and usually the last note in the melody. Each mode is paired with another that shares the same final. There are four finals, each with a unique combination of tones and semitones surrounding it, as shown in Example 2.5a, and outlined here:

|

Modes |

Final |

Interval below final |

Intervals above final |

|

1 and 2 |

D |

tone |

tone, semitone |

|

3 and 4 |

E |

tone |

semitone, tone |

|

5 and 6 |

F |

semitone |

tone, tone |

|

7 and 8 |

G |

tone |

tone, tone |

Because pitch is relative rather than absolute in chant, it is the intervallic relationship to the surrounding notes that distinguishes each final, not its absolute pitch.

Authentic and plagal modes Modes that have the same final differ in range. The odd-numbered modes are called authentic and typically cover a range from a step below the final to an octave above it, as shown in Example 2.5a. Each authentic mode is paired with a plagal mode that has the same final but is deeper in range, moving from a fourth (or sometimes a fifth) below the final to a fifth or sixth above it. Because Gregorian chants are unaccompanied melodies that typically use a range of about an octave, the effect of cadencing around the middle of that octave in the plagal modes was heard in the Middle Ages as quite distinct from closing at or near the bottom of the range in the authentic modes. Modern listeners may find this difference hard to understand, since we consider both Row, Row, Row Your Boat and Happy Birthday to be in the major mode, despite the different ranges of their melodies in respect to the tonic. But to medieval church musicians, the combination of different intervals around each final with different ranges relative to the final for authentic and plagal modes gave each of the eight modes an individual sound.

EXAMPLE 2.5 The church modes

Use of B Only one chromatic alteration was normally allowed: B

Only one chromatic alteration was normally allowed: B often appears in place of B in chants that give prominence to F, as chant melodies in modes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 frequently do.

often appears in place of B in chants that give prominence to F, as chant melodies in modes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 frequently do.

Species of fifth and fourth Some theorists applied to the modes the species of fifth and fourth described by Cleonides (see Chapter 1 and Example 1.3), as diagrammed in Example 2.5b. They divided each mode into two spans, marked by brackets in the example: a fifth rising from the final, and a fourth that is above the fifth in the authentic modes and below the final in the plagal modes. The arrangement of whole tones and semitones above each of the four finals is unique, corresponding to Cleonides’s four species of fifth, although in a different order; each scale is then completed with one of the three species of fourth. This way of looking at the modes clarifies the relationship between plagal and authentic modes, helps in analyzing some chants, and is very useful for understanding music in the Renaissance. In practice, however, the modes as used in medieval melodies were not really octave species, as the diagrams in Example 2.5b might suggest, but extended to a range of a ninth or tenth or more and often allowed B as a substitute for B, as shown in Example 2.5a.

as a substitute for B, as shown in Example 2.5a.

Reciting tone In addition to the final, each mode has a second characteristic note, called the reciting tone. The finals of corresponding plagal and authentic modes are the same, but the reciting tones differ (see Example 2.5). The general rule is that in the authentic modes the reciting tone is a fifth above the final, and in the plagal modes it is a third below the reciting tone of the corresponding authentic mode, except that whenever a reciting tone would fall on the note B, then it is moved up to C. The final, range, and reciting tone all contribute to characterizing a mode. The reciting tone is often the most frequent or prominent note in a chant, or a center of gravity around which a phrase is oriented, and phrases rarely begin or end above the reciting tone. In each mode, certain notes appear more often than others as initial or final notes of phrases, further lending each mode a distinctive sound.

Modal theory and chant The modes were first codified as a means for classifying chants and arranging them in books for liturgical use. Many chants fit well into a particular mode, moving within the indicated range, lingering on the reciting tone, and closing on the final. Viderunt omnes in Example 2.3 on page 33 is a good example. In mode 5, it begins on the final F; rises to circle around the reciting tone C, which predominates in most phrases; touches high F an octave above the final three times and E below the final once, using the whole range of the mode; uses both B and B , as allowed in this mode; and closes on the final. Most phrases begin and end on F, A, or C, as is typical of mode 5. But not all chant melodies conform to modal theory. Many existed before the theory was developed, and some of these do not fit gracefully in any mode. Chants composed after the modes were codified in the tenth century often have a very different style from older ones, making the mode clear from the outset and using few if any of the standard melodic figures associated with each mode in older chants.

, as allowed in this mode; and closes on the final. Most phrases begin and end on F, A, or C, as is typical of mode 5. But not all chant melodies conform to modal theory. Many existed before the theory was developed, and some of these do not fit gracefully in any mode. Chants composed after the modes were codified in the tenth century often have a very different style from older ones, making the mode clear from the outset and using few if any of the standard melodic figures associated with each mode in older chants.

Application of Greek names Beginning in the ninth century, some writers applied the names of the Greek scales to the church modes, as shown in Example 2.5b. Misreading Boethius, they mixed up the names, calling the lowest mode in the medieval system (A–a) Hypodorian, the highest in Cleonides’s arrangement of the octave species (a–a′), and moving through the other names in rising rather than descending order (compare Example 2.5b with Example 1.3c). In the resulting nomenclature, plagal modes had the prefix Hypo- (Greek for “below”) added to the name of the related authentic mode. Although medieval treatises and liturgical books usually refer to the modes by number, the Greek names are often used in modern textbooks and in discussions of modern music and jazz.

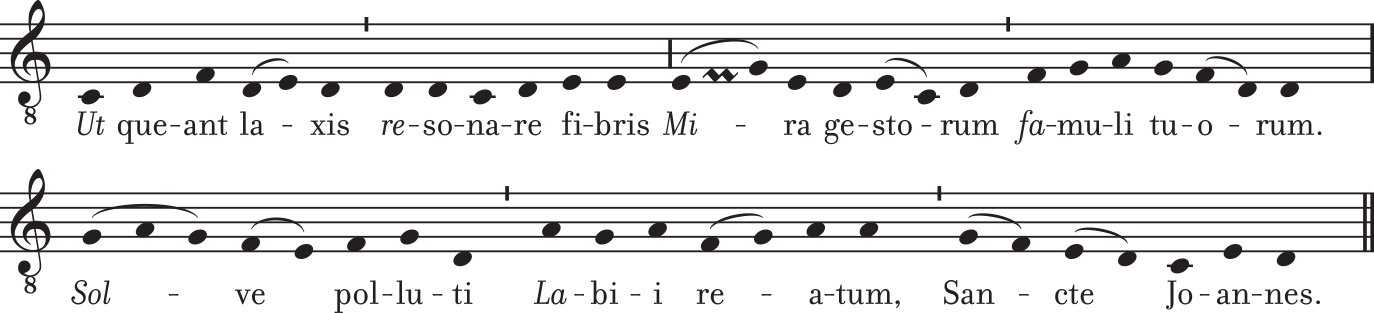

EXAMPLE 2.6 Hymn, Ut queant laxis

The attempts by medieval theorists to link their music to ancient Greek theory, despite the poor fit between the modes (which were based on final, reciting tone, and ranges exceeding an octave) and the Greek system (which was based on tetrachords, octave species, and tonoi), show how important it was for medieval scholars to ground their work in the authoritative and prestigious Greek tradition.

SOLMIZATION

To facilitate sight-singing, Guido of Arezzo, the inventor of the musical staff and author of the Micrologus (see p. 35), introduced a set of syllables corresponding to the pattern of tones and semitones in the succession C–D–E–F–G–A. He noted that the first six phrases of the hymn Ut queant laxis, shown in Example 2.6, began on those notes in ascending order, and he used their initial syllables for the names of the steps: ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la. These solmization syllables (so called from sol-mi) are still used, although the most common version of the set substitutes do for ut and adds ti above la.

Singers used solmization syllables then as they do now, to help form mental sound images of the intervals and apply them when singing. Within this set of six syllables are all the intervals singers were likely to find in chant melodies: the step between mi and fa is a semitone, and the other steps are whole tones; there are two minor thirds (re–fa and mi–sol) and two major thirds (ut–mi and fa–la); and all the fourths and fifths are perfect. Learning to associate these intervals with particular syllables made it easier to sing the intervals correctly.

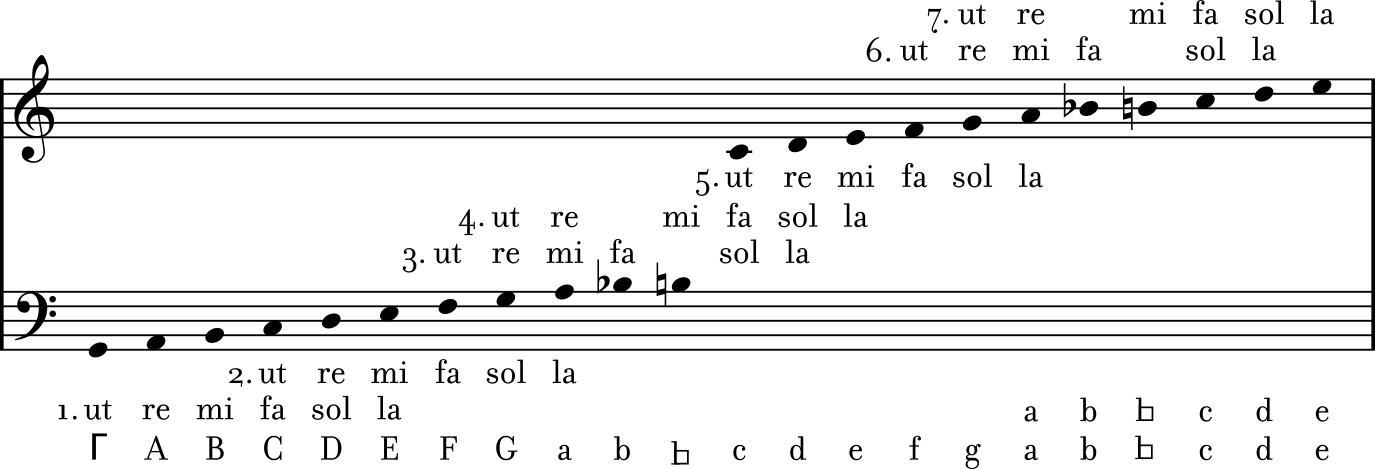

Later theorists mapped the solmization syllables onto the entire range of notes used in medieval music. Because the semitones E–F, B–C, and A–B must be solmized with the semitone mi–fa, the six-syllable pattern may be placed in seven different positions in this range, as shown in Example 2.7. (The chromatic semitone B

must be solmized with the semitone mi–fa, the six-syllable pattern may be placed in seven different positions in this range, as shown in Example 2.7. (The chromatic semitone B –B ♮ does not occur in chant.) A singer who had memorized these positions was ready to sing any melody using the syllables. Within this range, each specific note in the tone-system was named by its letter and the solmization syllables used with that note in that octave. For any note in Example 2.7, its medieval name can be found by reading its letter and syllables from bottom to top. Thus the lowest note was called gamma ut, from which comes our word gamut, and middle C was c sol fa ut.

–B ♮ does not occur in chant.) A singer who had memorized these positions was ready to sing any melody using the syllables. Within this range, each specific note in the tone-system was named by its letter and the solmization syllables used with that note in that octave. For any note in Example 2.7, its medieval name can be found by reading its letter and syllables from bottom to top. Thus the lowest note was called gamma ut, from which comes our word gamut, and middle C was c sol fa ut.

Mutation Using solmization to learn a melody that exceeded a six-note range required shifting the syllable set to different positions. For example, in the passage from Viderunt omnes in Example 2.8, no position can be found that contains all the notes: the first ten can be sung with the syllable set beginning on G (position 4 in Example 2.7), but the singer has to shift one position down to accommodate the B , shift down again for the low E, and shift back up for the C and B

, shift down again for the low E, and shift back up for the C and B in the cadential phrase. Shifting positions was done through a process called mutation, in which a singer renamed a note to fit the new syllable set, as shown in the example.

in the cadential phrase. Shifting positions was done through a process called mutation, in which a singer renamed a note to fit the new syllable set, as shown in the example.

EXAMPLE 2.7 Solmization syllables in the medieval gamut

EXAMPLE 2.8 End of Gradual Viderunt omnes in solmization syllables

© LEBRECHT MUSIC & ARTS

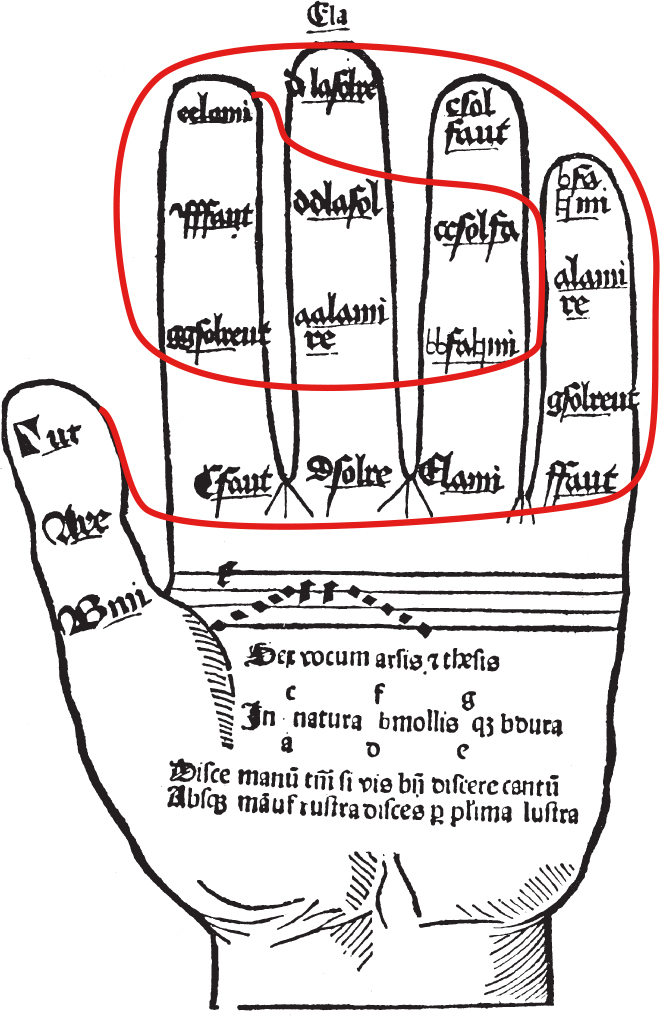

Guidonian hand Followers of Guido developed a pedagogical aid called the “Guidonian hand,” shown in Figure 2.11. Pupils were taught to sing intervals as the teacher pointed with the index finger of the right hand to the different joints of the open left hand. Each joint stood for one of the notes in the tone-system; any other note, such as F or E

or E , was considered to be “outside the hand.”

, was considered to be “outside the hand.”

Using solmization and staff notation, Guido boasted that he could “produce a perfect singer in the space of one year, or at the most in two,” instead of the ten or more it usually took teaching melodies by rote. No statement more pointedly shows the change from three centuries earlier, when all music was learned by ear and the Frankish kings struggled to make the chant consistent across their lands, or more clearly illustrates how innovations in church music sprang from the desire to carry on tradition.

- musica mundana

(Latin, “music of the universe,” “human music,” and “instrumental music”) Three kinds of music identified by Boethius (ca. 480–ca. 524), respectively the “music” or numerical relationships governing the movement of stars, planets, and the seasons; the “music” that harmonizes the human body and soul and their parts; and audible music produced by voices or instruments.

- musica humana

(Latin, “music of the universe,” “human music,” and “instrumental music”) Three kinds of music identified by Boethius (ca. 480–ca. 524), respectively the “music” or numerical relationships governing the movement of stars, planets, and the seasons; the “music” that harmonizes the human body and soul and their parts; and audible music produced by voices or instruments.

- musica instrumentalis

(Latin, “music of the universe,” “human music,” and “instrumental music”) Three kinds of music identified by Boethius (ca. 480–ca. 524), respectively the “music” or numerical relationships governing the movement of stars, planets, and the seasons; the “music” that harmonizes the human body and soul and their parts; and audible music produced by voices or instruments.

- mode

(1) A scale or melody type, identified by the particular intervallic relationships among the notes in the mode. (2) In particular, one of the eight (later twelve) scale or melody types recognized by church musicians and theorists beginning in the Middle Ages, distinguished from one another by the arrangement of whole tones and semitones around the final, by the range relative to the final, and by the position of the tenor or reciting tone. (3) Rhythmic mode. See also mode, time, and prolation.

- final

The main note in a mode; the normal closing note of a chant in that mode.

- range

A span of notes, as in the range of a melody or of a mode.

- reciting tone

The second most important note in a mode (after the final), often emphasized in chant and used for reciting text in a psalm tone.

- solmization

A method of assigning syllables to steps in a scale, used to make it easier to identify and sing the whole tones and semitones in a melody.

- authentic mode

A mode (2) in which the range normally extends from a step below the final to an octave above it. See also plagal mode.

- plagal mode

A mode (2) in a which the range normally extends from a fourth (or fifth) below the final to a fifth or sixth above it. See also authentic mode.